In 1960, a civil rights organization placed a fund-raising ad in the New York Times seeking donations for the legal defense of Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights activists. The ad described violence that had been committed by segregationist officials against civil rights protesters in Montgomery and other southern cities. Its publication led to a multimillion-dollar libel suit that produced one of the most crucial Supreme Court decisions protecting the freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

On the sixtieth anniversary of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, when many are encouraging the Supreme Court to reconsider or to overrule Sullivan, it is important to recall the history of the case and ask what it can teach us about the significance of freedom of speech to the pursuit of democracy and civil rights.

The story of New York Times v. Sullivan began long before any legal briefs were filed. In 1947, Turner Catledge, the managing editor of the Times, made a historic decision to place full-time reporters in the South to cover the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. The New York Times, the nation’s newspaper of record, was the first national news outlet to have a southern bureau. By the time civil rights activists in Montgomery, Alabama, embarked on a boycott of the city’s buses in 1955, most of the major news outlets had followed the Times and dispatched journalists to the South.

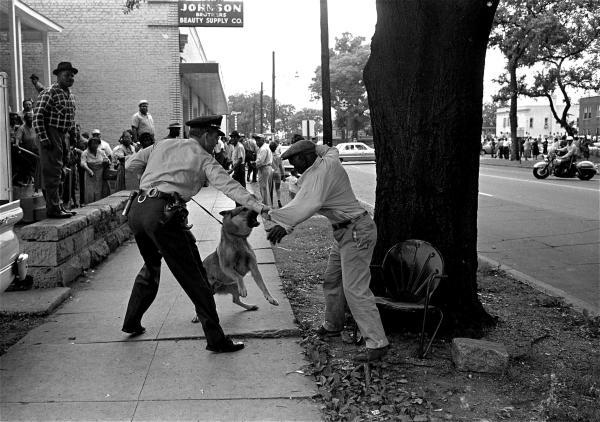

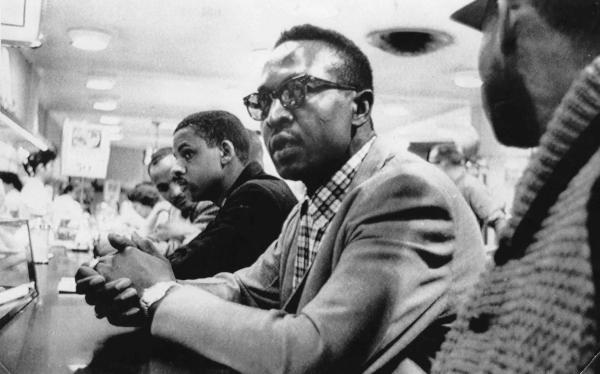

Segregationists resented this influx of journalists, which they likened to an “invasion.” They feared the power of the press to influence public opinion toward integration, with good reason. During the 1950s, the mass media were more influential than ever. The new medium of television was going straight into Americans’ homes. Images of activists being ejected from segregated lunch counters and brutally attacked by police highlighted the cruelties of the South’s racial system and the bravery of those who defied it. News coverage of civil rights protests and the violent backlash that those protests generated would prove critical in building national support for civil rights and the passage of such legislation as the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

By 1956, segregationists had embarked on a massive campaign to resist Brown v. Board of Education. It included the passage of laws to forestall integration, enacting violence against civil rights activists, and attacking the press, to halt its coverage of the Civil Rights Movement. Reporters who covered civil rights protests were beaten and assaulted, and journalists’ cameras were smashed. Libel suits became another weapon in this war on the press.

Since the nation’s founding, libel laws existed in all states to protect individual reputations against injuries caused by false and defamatory statements. Traditionally, libel laws were strict. Libel law was judged under the rule of “strict liability,” meaning that someone who published a defamatory statement could be liable even if they made the statement carefully. The only way that a speaker or publisher could defend a libel suit was to prove the truth of the statement “in all its particulars.” Although libel laws affected freedom of speech and the press—a newspaper’s decision to publish an article might well depend on whether it had reason to believe it could be sued for libel—the Supreme Court had said repeatedly before 1964 that defamatory statements were unprotected by the First Amendment and that libel law did not raise any constitutional free speech issues.

The South’s “libel attack” on the press escalated in February 1960, when four college students sat in at the segregated lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. The Woolworth’s protest ignited a sit-in movement across the South. Later that month, the sit-ins reached Montgomery, Alabama. Thirty-five students sat in at the segregated lunch counter at the Montgomery courthouse. The protesters were attacked by white mobs. Public affairs commissioner L. B. Sullivan, who supervised the police, permitted the mobs to attack the protesters while police stood by and watched.

Not long after this, Alabama authorities brought up Martin Luther King Jr. on phony charges of tax evasion. This was a ploy to remove King from the movement’s leadership and to bankrupt his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). A group of civil rights activists called the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South put an ad in the New York Times to solicit donations for the defense of King and the sit-in protesters.

The ad, which ran in March 1960 under the title “Heed Their Rising Voices,” described “an unprecedented wave of terror” that had been visited on protesters by “Southern violators of the Constitution.” It said that protesters in Montgomery had been expelled from school and that truckloads of police armed with shotguns and tear-gas had formed a ring around the Alabama State College campus. At the bottom of the ad was a plea for donations, along with the names of 80 eminent figures in the arts and in politics who endorsed the ad, including Sammy Davis Jr., Marlon Brando, and Eleanor Roosevelt. Also listed as endorsers were 20 ministers who led the SCLC. The ministers, in reality, hadn’t endorsed the ad or even known that their names were on it.

The ad contained minor errors about the events in Montgomery. For one, it said that protesters sang “My Country ’Tis of Thee” on the capitol steps, when they sang the national anthem. The ad said that King had been arrested seven times by Alabama authorities when he had been arrested only four times. The most serious error was a factually incorrect statement that officials had padlocked the dining hall of the Alabama State College to starve and to punish the protesters. The Times, which had been impressed with the eminence of the signatories, published the ad without checking its accuracy. This violated the Times’s policy of fact-checking all text that appeared in the newspaper.

Only 394 copies of the Times were circulated in Alabama. One went to the local newspaper, the Montgomery Advertiser. Editor Grover Hall had a grudge against the Times for its pro-integration stance. When Hall recognized that there were mistakes in the ad, he saw an opportunity to sue the Times for libel. Hall and a Montgomery attorney named Merton Roland Nachman Jr. encouraged three officials, including Sullivan, to sue the Times and four leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference whose names appeared on the ad as endorsers.

The Alabama officials said that they had been defamed by the ad because it accused them of being complicit in brutality against the protesters. In reality, such an accusation would hardly injure their reputations; being known for committing or abetting violence against civil rights protesters would have enhanced the reputations of a public official in Montgomery at the time. Moreover, these accusations were true—the officials had, in fact, abetted violence, although perhaps not all of the specific acts that they were accused of. None of the officials was actually mentioned by name in the ad (which referred generally to the “police” and to “authorities”). Yet, under Alabama’s libel laws, all that a plaintiff had to demonstrate was that the statements had the potential to injure someone’s reputation. The Times and the ministers couldn’t use the defense of truth because there were errors in the ad.

Sullivan and three other Alabama officials each sued the Times and the four civil rights leaders for half a million dollars. Alabama governor John Patterson then sued the Times and the civil rights leaders for one million dollars for purportedly being defamed by the ad. Seven officials in Birmingham, including the notorious Bull Connor, sued the Times for more than three million dollars over the paper’s reporting on official violence against civil rights activists in that city. As a result of the libel suits, the Times faced the possibility of bankruptcy. In a historic move, the Times took its reporters out of Alabama to avoid further libel suits. The nation’s newspaper of record had no journalists in Alabama during crucial years of the Civil Rights Movement. Other publications contemplated taking their reporters out of Alabama. The libel suits were having what soon came to be known as a “chilling effect” on the press.

In November 1960, an all-white jury awarded Sullivan $500,000, the largest libel verdict in history. Shortly after, the mayor of Montgomery won another half-a-million-dollar libel judgment against the Times and the ministers. These victories spurred copycat lawsuits. By 1964, southern officials had brought 17 libel suits against media outlets seeking damage awards of more than $288 million.

The SCLC was hemorrhaging money. A fledgling, grassroots organization, the SCLC couldn’t advance its aims or its projects, including freedom rides and sit-ins, if its leaders were saddled with multimillion-dollar libel judgments and defensive litigation battles. Officials had sued some of the most prominent leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. Ralph Abernathy was a cofounder of the SCLC who had been a leader of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Solomon Seay had been involved in grassroots civil rights activities in Montgomery since the 1930s. Joseph Lowery was another founder of the SCLC. Fred Shuttlesworth, who held the record as the “most jailed civil rights leader,” had been beaten by mobs and imprisoned for his efforts to desegregate Birmingham.

Alabama authorities seized the ministers’ property to pay the libel judgments. They auctioned Abernathy’s farmland and hauled away Shuttlesworth’s used Plymouth. King described the libel cases as a “civil rights crisis.”

After losing their appeals to the Alabama Supreme Court, the Times and the ministers appealed separately to the U.S. Supreme Court. The ministers’ appeal focused on segregation and the racial animus that had given rise to the libel suits. The Times, represented by Columbia University law professor Herbert Wechsler, focused on libel law’s threat to freedom of the press. To avoid confronting the Supreme Court’s well-established position on the constitutionally unprotected status of libel, Wechsler brilliantly shifted the focus of the appeal from the right to protect individual reputation to the right of citizens to criticize the government. Wechsler argued that permitting Sullivan to recover damages for libel on the theory that he was defamed by criticism of the “police” in Montgomery was akin to the old crime of seditious libel, the crime of criticizing the government, which no longer existed in the United States and had long been assumed to be unconstitutional.

“One of the prime objectives of the First Amendment is to protect the right to criticize ‘all public institutions,’” Wechsler argued.

Wechsler made the sweeping argument that there is an unconditional right to criticize the government and its officials—that such criticism was protected entirely by the First Amendment, even if the criticism was false and intentionally injured an official’s reputation. Knowing that this radical argument likely wouldn’t win, Wechsler offered other reasons why Sullivan’s judgment should be thrown out. The ad didn’t mention Sullivan by name. There was no injury to Sullivan’s reputation. In passing, Wechsler’s argument proposed a version of what ultimately became the rule of Sullivan, the “actual malice” rule.

It isn’t difficult to figure out why the Warren Court voted to hear the cases of the New York Times and the ministers. The Court engaged with the cases out of its concern for the Civil Rights Movement. In a series of previous decisions, the Warren Court had already transformed deeply rooted patterns of segregation and discrimination. Major news outlets such as CBS said that they would have stopped covering the Civil Rights Movement if Sullivan’s judgment hadn’t been reversed. The Court was also interested in the First Amendment issues at stake. The relationship between libel law and the First Amendment was an important constitutional question that the Court hadn’t addressed before.

After the oral arguments in January 1964, all of the justices made clear in their comments that Sullivan’s verdict had to be reversed. Yet the grounds for reversal were a matter of debate. Justices Hugo Black and William Douglas supported Wechsler’s broad argument, but the other justices weren’t willing to go that far. They believed that there should be some protections for the reputations of public officials, and that those protections should be balanced against freedom of speech. But how to strike that balance was unclear. In memoranda and discussions, the justices debated the legal standard for several weeks.

Chief Justice Warren asked Justice William Brennan to write the opinion. Brennan had a deep commitment to civil liberties and civil rights, was the author of seven First Amendment opinions, and was a remarkable negotiator and unifier, with a talent for bringing the justices together behind a unanimous opinion. Brennan wrote and circulated to the other justices eight drafts of the opinion in which he developed the actual malice rule. Under actual malice, a public official can recover damages in a libel suit only if the official can show that the defamatory statement was made with knowledge that the statement was false or with “reckless disregard of whether it was false or not,” which means that the speaker or publisher had strong reason to believe the statement was untrue and went ahead and made it anyway. This sweeping rule was used to strike down the judgment against the Times and the ministers.

Brennan created the actual malice rule to address the extreme circumstances of the case. He knew that a negligence standard, a standard of carelessness, the usual fault standard used in personal injury cases, wouldn’t have protected the Times since it admitted that it had been careless in publishing the ad without checking the facts. Brennan also saw another reason for adopting actual malice. Even a carelessness standard, he believed, wouldn’t provide publishers with the latitude that they needed to make statements that were critical of public officials. Such latitude was especially important for news outlets that published on deadlines and may not have a chance to verify every assertion. Presented with rules that were overly strict, publishers would restrain themselves and only make statements which “steer far wider of the unlawful zone,” as Brennan put it. Freedom of speech, he wrote, needed “breathing space” to survive.

On March 9, 1964, Brennan announced the unanimous opinion reversing Sullivan’s judgment. The Court put constitutional limitations on libel law and radically shifted the balance between the protection of free speech and the protection of reputation. Brennan recognized that under actual malice, harms caused by some false statements would go unremedied. But this was the price of freedom of expression, he explained. “Erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate, and . . . it must be protected if the freedoms of expression are to have the ‘breathing space’ they ‘need to survive,’” he wrote.

Even more important and far-reaching was the vision of the First Amendment announced in Sullivan. For the first time, the Court declared the freedom to criticize the government and its officials a “central meaning” of the First Amendment. This was part of what Brennan described as America’s “profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.” Such debate, Brennan wrote, may well include “vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.” This language represented the most forceful articulation of the role of freedom of speech in democracy. It has undergirded dozens of First Amendment decisions and provided the foundation of modern free speech law.

The Supreme Court’s decision saved the Times from ruin. Sullivan reversed L. B. Sullivan’s judgment and turned back the “libel attack” on the press. It freed the press to report fully and freely on the Civil Rights Movement. Reporting on protests in Selma, Alabama, the following year helped bring about the national consensus on civil rights that led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Sullivan was one of the most important Supreme Court decisions furthering the advance of the Civil Rights Movement.

Sullivan transformed journalism. It enabled the press to report on public affairs without fear of devastating libel suits. It permitted the development of investigative journalism as a genre. Historic disclosures about the Vietnam War and Watergate might not have occurred if the press lacked the shield of Sullivan.

Commentators heralded Sullivan as a momentous occasion in the history of freedom of speech, an occasion for “dancing in the streets,” in the words of political theorist Alexander Meiklejohn. Yet Sullivan was criticized since practically the day it was handed down. Critics have alleged that Sullivan led to irresponsibility in journalism. Some have said the Court didn’t give enough weight to the interest in reputation. Criticism of Sullivan increased in 1967 when the Supreme Court extended the actual malice standard to libel cases involving “public figures,” a category of individuals it defined as any person who is not an elected official but who gets involved in public life, even in a minor way. Some have argued that this “public figure” doctrine has no relationship to the “central meaning” of the First Amendment as declared in Sullivan, the right to criticize public officials. Recent critics, including Supreme Court justice Neil Gorsuch, have pointed out that our social and media landscape have changed with the rise of the internet and social media, affecting the ease with which people can be defamed, and that libel law should be adjusted to reflect these realities.

Sullivan has gone down in history as a case about freedom of the press. The civil rights dimension has been obscured in most discussions. The opinion barely mentioned the Civil Rights Movement because Brennan wanted to achieve a broad ruling that would protect freedom of speech and press beyond the civil rights context. The media covered Sullivan as a case about free speech and not about civil rights.

Yet no one reading the headlines in 1964 could have ignored Sullivan’s relationship to the Civil Rights Movement. Sullivan was the product of marches in the streets in Birmingham; it was the result of the onslaught of libel cases coming from the South and the threat that they posed to the press. It was the consequence of beaten and bloodied Freedom Riders and Bull Connor’s attacks. It was the vindication of a growing public consensus in favor of civil rights. The Warren Court knew that civil rights could not be achieved without protections for freedom of speech, assembly, and association. Through First Amendment cases involving the Civil Rights Movement, the Court began forging a body of free speech law that would strongly protect not only civil rights activists but all dissenters, from antiwar protesters to hate groups like the Westboro Baptist Church.

This article was adapted from the author’s 2023 Constitution Day lecture at the Law Library of Congress.