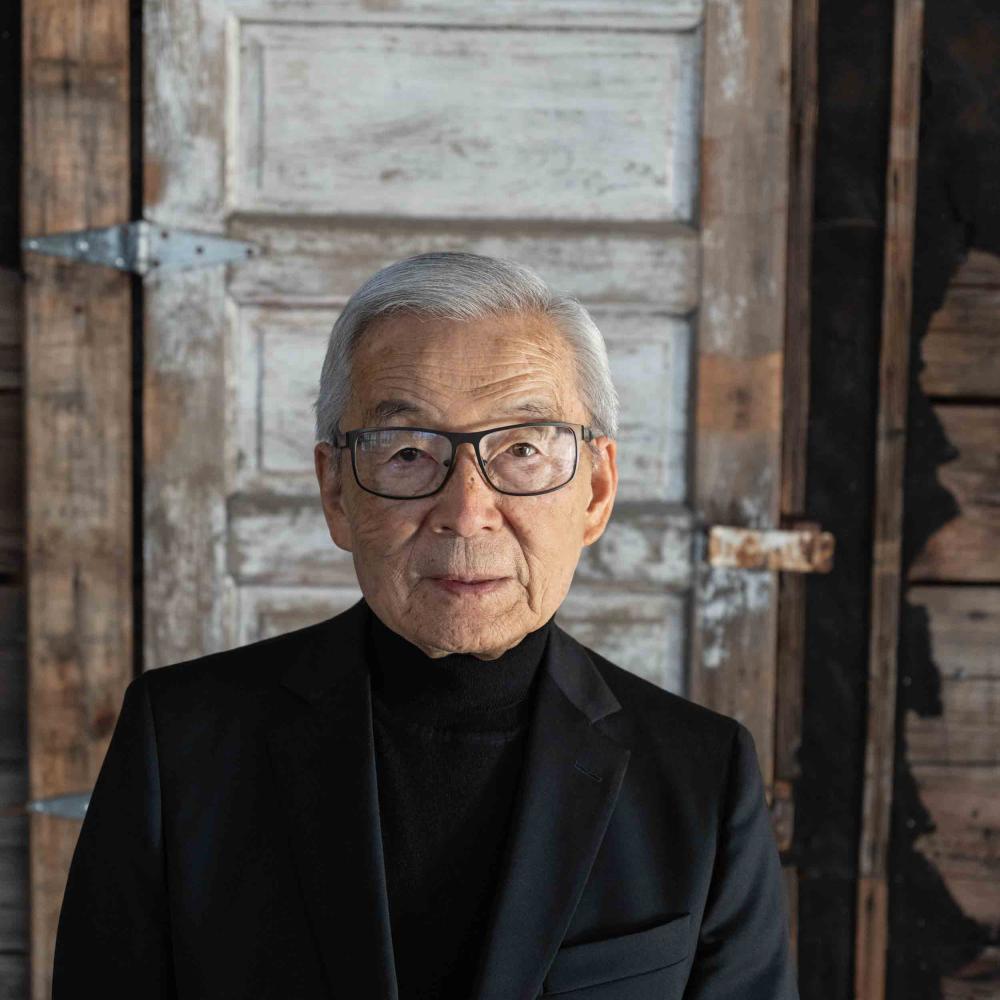

Born in San Francisco in 1933, Sam Mihara was nine years old when he and his family were sent by the United States government to Heart Mountain War Relocation Center in northern Wyoming.

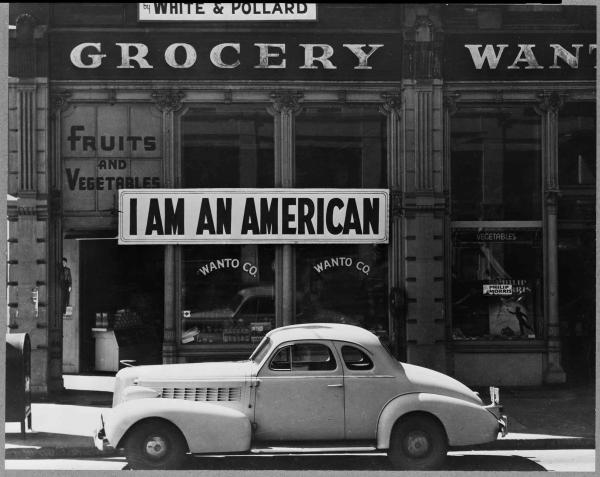

More than 120,000 Japanese Americans, many of them U.S. citizens, were thus forcibly removed from their homes and, without due process, imprisoned, en masse, amid the hysteria that followed Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, which drew the United States into World War II. The act of sending Japanese Americans to live in confinement at a total of ten different large-scale camps in the western United States has been called internment, detention, incarceration, and worse. President Truman and many others referred to these detention centers as “concentration camps.”

An engineer and an executive, Mihara worked for more than 40 years for Boeing before retiring in 1997. In 2011, he began devoting his time to speaking publicly about his own experience and the greater ordeal of Japanese Americans during World War II.

SHELLY C. LOWE (NAVAJO): So good to see you, Sam. It is so wonderful to be here at the Japanese American National Museum. You know, this institution has done a lot to tell the history of Japanese Americans in this country but also the difficult history of Japanese incarceration. But before we talk about that, tell me about your childhood and what life was like before the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

SAM MIHARA: Well, keep in mind I was pretty young. I grew up in San Francisco, in the heart of what they called “Japantown,” and we lived in a three-story Victorian in the middle of San Francisco, and I had a very, very pleasant childhood.

My parents were quite successful. My father was an editor of a major newspaper, an English-Japanese bilingual newspaper. Our immediate family included my two parents, an older brother, and myself. But our house was very large. So we had my four grandparents, an aunt, and a dentist and his wife in the three-story Victorian house. We spoke Japanese to our parents and grandparents, but we spoke English to all our school-age friends. We celebrated Easter, Christmas, and other American holidays. But we also celebrated Japanese events, like Boy’s Day and New Year’s Days (usually the first three days of the new year). We ate American dishes like hamburgers and spaghetti. And we also enjoyed Asian dishes like sukiyaki, sushi, and chow mein. I was in grammar school, and life was quite comfortable until the attack on Pearl Harbor and until President Roosevelt signed the executive order that gave the military the power to remove us. It turned out that out of the five military district leaders in the country, only one decided to remove Japanese from the West Coast and his name was Lt. General John DeWitt. Japanese Americans were singled out among other nationalities. DeWitt did not remove German or Italian families. After that, all hell broke loose. The government forced us out of our homes and moved us to a terrible place in northern Wyoming.

LOWE: So your father was an editor. Did you have conversations in your home about what was going on, about the war? Or did you feel like all this was just coming out of nowhere?

MIHARA: On December 7, 1941, while the attack on Pearl Harbor was taking place, I was in a neighborhood theater. On December 8, I remember seeing the headlines and I asked my father why Japan would do such a thing. And his answer was that he did not know. I don’t know why they did that. More important, I found out my father and my mother were very worried because they were not American citizens. They were Japanese, called aliens at that time, and they were very worried because they feared the government would force them to go back to Japan and leave the kids here. So that really bothered them.

LOWE: You were made to go to Heart Mountain. How did that trip unfold? And what happened to everything in your three-story Victorian house?

MIHARA: It was really devastating for most families. General DeWitt gave us only one week to take care of our property, store whatever things that were valuable, and report to the buses to take us away. I remember my father was very concerned as to what he was going to take with him.

The government said you can only take one suitcase. There’s a display of suitcases here. Everything we brought with us had to fit in one suitcase. We didn’t know where we were going. We only learned that we were going to Heart Mountain after we got to Heart Mountain.

My mother packed my suitcase with California-type clothing. We had no idea. That first winter the temperature fell to minus-28 degrees. It was really tough, but that was the nature of what had happened to all of us in one short week.

Most people lost their property. They lost their homes and much else. There were Japanese farmers who had fruit farms: They lost their property because they were forced to sell at a very small price. I know of one family that had a strawberry farm near San Jose, California, and about 14 acres. They were forced to sell for a very small amount of money, like $25 an acre, and recently the Apple Corporation bought a similar sized property for the total amount of half a billion dollars.

A lot of people lost their homes in San Francisco, but, fortunately, my father had connections. He knew a white attorney in San Francisco who with his wife took care of our home while we were gone. After the imprisonment, though not immediately, we were able to go back to our home when we came back to San Francisco. But it was a very traumatic time. People lost a lot of property.

LOWE: Was your family able to pick up where they had left off when they got out of internment? What about your parents?

MIHARA: Well, my father had a medical problem, a case of glaucoma. He had had it since college, but in San Francisco he was able to find a specialist who knew how to treat it.

At Heart Mountain, however, no one knew how to take care of glaucoma. There were general practitioners, doctors who knew how to take care of emergency problems, but no one knew how to treat glaucoma. And General DeWitt would not let my father go home for even a short visit to see his specialist. As a result, my father went blind and never saw again. That was a financial disaster. He lost his source of income, and it really was a tough time after the war.

LOWE: You were nine years old when you went to Heart Mountain.

MIHARA: Correct.

LOWE: Did you understand what was happening? What was it like to have a childhood that was so disruptive?

MIHARA: During the week, we were busy going to school, grammar school. By the way, the grammar schools were terrible. They only had non-certified teachers from within the prisoner ranks. No outside teachers at my grade level were brought in to help.

Outside of school time, there was a real problem. What to do with ourselves? We had a lot of time on our hands and my brother noticed that sometimes the guards were sleeping in the guard towers.

One day they never showed up to work. So my brother said, “Let’s go have some fun.” We went to the barbed wire fence, spread it apart, and walked outside. We went looking around the countryside, and the first thing we found were Native American arrowheads from the Crow Tribe on the ground. The Heart Mountain area was part of the Crow Indian territory prior to the reservation relocation. So we started collecting arrowheads.

And then my brother noticed there were rattlesnakes. We didn’t have rattlesnakes in San Francisco. This was going to be fun. So my brother taught me how to capture a rattlesnake. You create a stick with a forked end, and you just stab it to hold the snake down. Then we would do things like cut off the tail. We made a collection of rattlesnake tails. And we had some other ways of occupying ourselves or having fun.

LOWE: I learned that the local Boy Scout troops would come to Heart Mountain. Did you do Boy Scouts?

MIHARA: I was Cub Scout age, but my brother was Boy Scout age. There were some 12 different Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops at the camp. It was a very active program. Our parents helped to create it to keep the young people busy. One of my friends was Norm Mineta. He lived in San Jose. He was my brother’s age, and he was in the Boy Scouts. And there was a young fellow in the town of Cody, Wyoming. His name was Alan Simpson. He became a senator, a retired senator now, but in those days he was a Boy Scout. He came to camp and he developed a friendship with Norm Mineta, who later served in the House of Representatives and as the secretary of transportation. The bond between these two men, which started in the internment camp, continued to grow, and was finally memorialized in the Simpson-Mineta Institute, which now exists at the Heart Mountain site. The Boy Scout system helped develop relationships and keep the young people busy and that was very, very important, you know.

LOWE: One of the most well-known names from this time was Fred Korematsu. Who was he, and why should we know Fred?

MIHARA: Fred was very unusual. He was Nisei, which means his parents were Japanese immigrants but he was born in the U.S., and a little bit older than me. He was one of three Japanese Americans who refused to go to camp. The reason why Fred refused to go was that he had a girlfriend, not just any girl. She was a white girl in the Bay Area, an Italian girl. Fred didn’t want to go to camp, so he went to a plastic surgeon to make him look Anglo, not Japanese.

The surgeon failed. Fred still looked Japanese. As a result, the police caught him. A lower court found him guilty of disobeying Lt. Gen. DeWitt’s orders and the case went to the Supreme Court, which agreed with the lower court. They didn’t take up the issue of constitutionality. They simply said, You disobeyed General DeWitt’s orders and so you have to go. As a result, that case became very famous as an example of the leadership of the country ignoring our constitutional rights.

There were two more who had resisted, but those are the only three recorded objections. Everyone else, 120,000 of us, decided to go along with the imprisonment.

LOWE: What brought about the end of internment?

MIHARA: Well, a different decision from the Supreme Court that was handed down on the same day the Korematsu decision was issued. This decision involved a lady named Mitsuye Endo, a Japanese American citizen of the United States whose rights were violated by imprisonment. So the attorney filed a lawsuit and the Supreme Court decided, unanimously, by nine to zero that you must let her go and let the rest of the people go because the War Relocation Authority did not have the power to remove and detain American citizens without evidence of espionage.

Shortly after that my father asked the government if he could return to San Francisco to make work arrangements. The government told my father not to go back to San Francisco because the hate was so terrible. So we first went to Salt Lake City, but it didn’t work out. Business was not very good and so mother insisted we go back home.

So, in 1948, more than six years after Pearl Harbor, we went back home to reestablish our lives.

LOWE: My understanding is that the government provided bus tickets for individuals and you got to choose where you would go. Is that how it worked?

MIHARA: Yes, the bus took us from Heart Mountain to Salt Lake City. We had trouble finding housing but finally found a place in a low-income part of town. My father tried to establish a business in Salt Lake City, selling cultural items from Japan, but it turns out there’s not much of a market in Salt Lake City for Japanese artifacts. That’s when mother said, “No. We’ve got to go back home.” So after three years in Salt Lake City, we left.

LOWE: Your family went through these years of hardship, but then you did very well for yourself. Tell me a little about your education and career.

MIHARA: We finally got home to San Francisco and our whole family was facing a lot of hate, but our parents figured out the solution to the problem is to make sure the young people get a good education.

They focused on getting us the best possible education they could afford. And if you live in San Francisco, the most affordable best education was at Berkeley across the bay. They couldn’t afford Stanford, but they could afford Berkeley. Many of my friends went to Berkeley. And most of them became professionals, doctors and lawyers and pharmacists, and they’ve done very well.

LOWE: You went to Berkeley as well?

MIHARA: I went to Berkeley. In high school, I was interested in math and sciences, and a good friend of mine recommended I major in engineering. So I went to Berkeley and majored in engineering. I went to UCLA Graduate School and earned a master’s in engineering and the Boeing Company—at that time it was called Douglas Aircraft but now it’s called Boeing—offered me a job. The wages were unbelievably high. I had never earned so much money in my life.

I had a great 42-year career at Boeing. I really enjoyed helping develop rockets, rockets that put up satellites, rockets that went to the moon. It was a great, great time, and I owe my thanks to Boeing for treating me so well. After I retired, I started speaking about what happened during the war.

LOWE: So you went to Berkeley, studied at UCLA, and started working at Boeing. Did you face a lot of prejudice in those years in these places?

MIHARA: I understand the question, and the answer is I did not detect any hatred against Japanese as such, but I did clearly hear from other students about hate against others, in particular against Jews, in particular against Latinos. I heard about people using derogatory terms for other minorities. So I knew prejudice existed, but I never heard anyone talk bad about Japanese at that time, no.

LOWE: So, you’re going to be giving the NEH Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities and you come out of a non-humanities profession and career. Tell me how you transitioned then and why was it so important for you to turn to humanities and use the tools of humanities to tell your story.

MIHARA: I was in retirement. I wanted to continue having fun in my retirement. About 15 years ago, I received a call from the folks at Heart Mountain who had received a call from the Department of Justice, which was planning on a conference of lawyers who worked for the Department of Justice, and they were looking for somebody who could remember what happened at the camp.

So I went to the conference and there was a room of about a hundred attorneys, and I noticed something interesting. The lawyers were seated in order of rank. The most senior lawyers sat in the front and the youngest lawyers sat in the back.

I started my lecture by asking two questions. Question 1: How many of you have heard the name Fred Korematsu? No one in front raised their hand. Way in the back, though, were three young attorneys who had their hands up. So I gathered that 97 percent of the lawyers who worked for the Justice Department had never heard of Korematsu. That’s terrible.

I asked my second question. How many of you have heard the name Mitsuye Endo? No one raised their hand. So I thought, Oh, this is going to be easy. They know nothing about important events of our incarceration. So the stories of what happened to Korematsu and Endo became the framework for my talk.

I found out that the leader of that conference later sent a message to all the U.S. Attorney offices in the country saying, You must hear Sam. So I wound up talking at many DOJ offices. I spoke to a teachers’ conference, a history teachers’ conference, and I found out that hundreds of teachers wanted to hear me teach at their schools. I’ve now spoken to over 500 schools and, at last count, it’s around 120,000 students that I’ve taught all over the country and overseas.

LOWE: Well, that’s a very large impact, I think.

MIHARA: Yes.

LOWE: So, you know, you’ve had these years to tell this story, and then to process it for yourself. We talked a little bit before we started this interview about what it means to accept what has happened and what it means to be patriotic after the history that you’ve lived through.

MIHARA: One might ask, Did I lose faith and patriotism in the U.S.? Did I become bitter? The answer is that I was angry for a while, but I quickly learned that it does not help to remain bitter. And it is far better to educate people so the same mistakes will not happen again.

Well, you know, another important question is, Could it happen again? And my answer is it already happened because after 9/11, when the government rounded up over a thousand Muslim Americans and put them away in detention. So it happened.

Today, there are immigrants, children of immigrants, mothers with children who are being imprisoned today, and I’ve been to some of those prisons in Florida, Texas, Arizona, and California. I’ve interviewed some of the people, and I’ve learned the conditions are not very good. It’s no place to detain people, especially children, and so I’m against this process of continuing to build more prisons and there must be a better solution than we have today about the immigration problem.

Placing young people in prison is not the right answer. Hopefully, there will be a better answer some day.

LOWE: Do you still find that individuals are not aware of this history of Japanese American internment?

MIHARA: In my talks, I have found many people, many young people especially, are not being taught what happened. Once in a while, I’ll hear a response like, Oh, I remember hearing something about putting some Japanese into prisons, but that’s all they know. They don’t know why. They don’t know what the conditions were. And very few people know that it could happen again.

LOWE: What do you think needs to happen for us to make sure that this history is a part of the knowledge that everybody in this country learns and knows and understands?

MIHARA: There was an important congressional hearing on internment. It cited several factors that made internment possible in the first place.

One, there was hate. Two, there was a lot of hysteria with newspaper headlines and billboards urging people to demand that we be removed. There was also greed, people who wanted our property. But, most important, there were leaders of the country who failed to honor the Constitution. When Roosevelt signed the executive order, directly in violation of the Constitution, he denied our liberty and our rights, our civil rights.

LOWE: Do you ever talk about what came out of World War II, particularly the atomic bombs that were dropped on Japan?

MIHARA: My opinion is that dropping the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was a bad decision. If there had to be use of a bomb, it would have been more humane to select targets that are not harmful to the public, perhaps military targets. To create havoc and destroy families with a single bomb is not physically good or morally good. I wish they had done something else.

LOWE: The United States government formally apologized for the internment of Japanese Americans. How did that play out in the Japanese American community?

MIHARA: Well, when I saw the apologies in writing, I thought that was good news. It was nice to have apologies from the leadership of the country, but an apology alone doesn’t keep it from happening again.

In my talks, I present evidence of these apologies. I show letters signed by presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. It helps but it’s not the perfect solution. I wish more people, more leaders of this country, would apologize, but I’m grateful that at least Reagan and George H. W. Bush felt it was important to put it in writing. That was very, very appreciated.

LOWE: So I asked about this because we just had an apology from President Biden for the U.S. government’s role in the federal Indian boarding school system, which in many cases treated Native Americans in a way almost similar to what was done to Japanese Americans with incarceration camps. And there are other connections to Native Americans in this history. The Gila River Reservation in southern Arizona, for example, was the site of one of the incarceration camps. Is there an ongoing relationship between tribal communities and families that were in the incarceration camps located on the reservations?

MIHARA: The answer is yes. I’m quite familiar with the situation at Heart Mountain. That area and most of Montana and northern Wyoming was once the territory of the Crow Tribe. So it became very important for us as historians to make sure we recognized that this was their land before we got there, and so we’re taking steps to honor that background.

For example, we have an organization at Heart Mountain called the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation and the director of our historical activities is a fellow named Johnny Tim Yellowtail, who was a descendant of the Crow. He is helping to integrate the legacy of the Crow Tribe into our activities. At the last pilgrimage, we had Crow members participate in events so that people who come to our pilgrimage will learn the background of the Crow people in our history.

LOWE: What kind of historical research have you done? Have you been in the archives? Have you had to go and look and find some of this information for yourself?

MIHARA: The answer is yes. I did the best I could to source information. I read all of the minutes of the congressional hearing. That was a good source. But I wanted to learn more. I wanted to learn the answer to the question why. Why did people do those things?

Well, I could not get a why from General DeWitt because he’s dead. He’s buried, and I couldn’t talk with him, but I was able to find people who knew about major events during that time.

Fred Korematsu has passed, but his daughter, Karen Korematsu, is still alive and active, so I interviewed her. I did not know why Fred Korematsu resisted and she told me. She told me about his girlfriend, and then I wanted to find out what motivated Mitsuye Endo’s lawsuit, so I interviewed Jim Purcell. He is the son of the original attorney, James Purcell, who filed the Endo case. Jim told me his father had learned about the conditions in the camp, that people were living in horse stalls. So James decided to do something that no other white attorney would do, which is to file a lawsuit against the government saying it was unconstitutional. Thanks to Jim Purcell, the son, for telling me that story.

So that’s how I developed my background to learn the answer why. Why did these important people do what they did? That’s the heart of my talk: to explain to people that it was a humane reaction to the injustice that had happened.

LOWE: I like that. I often tell people that when we do work in the humanities, you know, it’s easy to do the who, what, when, and where. The hard part is often the how and the why, so I appreciate you trying to answer the why of the situation.

So what do you hope comes out of telling this history? What do you want individual young people in 50 years to be thinking and doing to move this work forward?

MIHARA: Yes. A lot of young people ask me, “What can I do? I’m only a student.” I point out, no, you can do something.

The cause of this injustice was primarily the leadership. The leaders of this country can decide to either honor the Constitution or ignore it. You have to help make sure that we don’t have those leaders taking those actions. So learning about what happened and taking steps to make sure that our leaders make the right decisions to honor the Constitution, that’s the best, most important thing to do. That’s what I try to teach.

LOWE: I don’t have any other questions. Is there anything else you want to share, any other highlights?

MIHARA: Well, I really appreciate the efforts of NEH. I really appreciate the honor of being selected, and I’m very grateful to your efforts to bring this to light and to bring such a large audience.

I realize I’m the first Japanese American to be honored and that’s always a nice thing to be able to say.

LOWE: You’re the first Japanese American and you’re probably going to be one of our oldest lecturers, which I think is absolutely fabulous.

MIHARA: I’ll be ninety-two in February. Well, I guess I’m the oldest, also the first Japanese American, the first former prisoner, and the first rocket scientist to receive the award. Lots of firsts.