My wife, Karen, and I were married in 1986. Raising a family was always part of the plan and, like other parents-to-be, we had lots of discussions about how our children would be raised, how they would be educated, and how to share our values and knowledge as parents.

Karen and I are baby boomers. We were open to possibilities our parents hadn’t considered, like moving away from family and attending college to advance our education. We discussed the possibility of homeschooling our kids as a way to pass on the best parts of ourselves. One unique consideration for us was a shared desire to give our children a strong identity, one that would be nurtured, we hoped, by passing on my heritage language and Indigenous culture. There was just one problem: I didn’t grow up speaking my heritage language and did not know its current status.

I am a citizen of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, having inherited my tribal identity through my father’s line. Karen is not Native. She is of German and European ancestry. I don’t disregard the many lines of heritage that make me who I am, but my forefathers ensured my tribal heritage was front and center in my life by reinforcing details of family and tribal history. For that reason, I was interested in strengthening that identity in my children. It’s important to note that I grew up away from my tribal community, in an urban setting in northwestern Ohio, and felt a strong urge to reconnect with my tribal community. I saw my heritage language as a way to strengthen those connections.

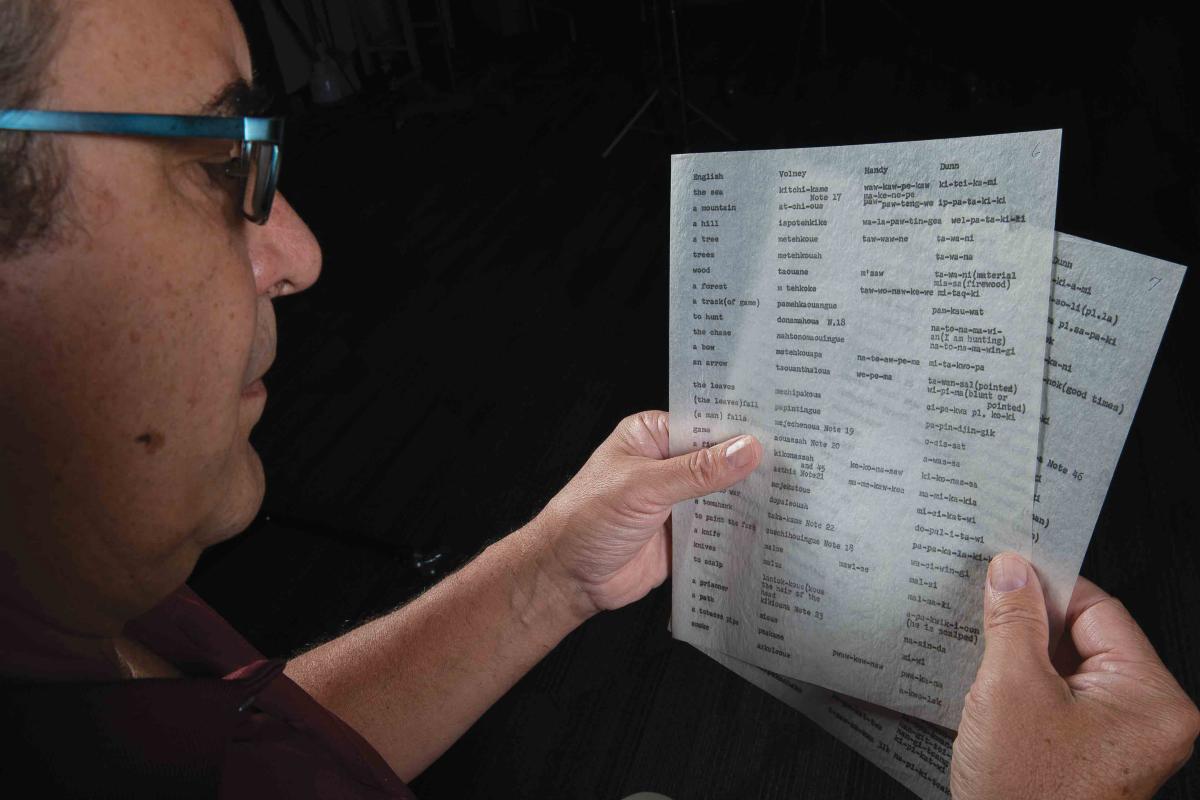

I had always had exposure to family names such as mihšihkinaahkwa (Little Turtle), amehkoonsihkwa (Beaver Woman), eepiihkaanita (Ground Bean), pimihsaahkwa (Going past), and šoowaapinamwa (Whirlwind, Tornado), but, in nearly every case, my family had lost their knowledge about the meaning of those ancestral names. In my late twenties, long after my grandfather had passed in the 1970s, I found among his belongings that had been given to me by my father several pages of language materials that piqued my curiosity. I knew this language was not from my grandfather as he had not been raised to speak his native language.

“Of course, we had a language,” I remember thinking. Was it still spoken? Was there a way I could learn to speak it? All these questions began to flow through me, and I became determined to find answers.

My father was still alive at the time, so I asked him where I might find someone who knew the language. He told me I would need to visit the Miami communities in Indiana and Oklahoma to find out, because he didn’t know. In the early 1990s, I made trips to both places, where tribal elders were living, and learned the last speakers of our language had passed by the early 1960s, about the time I was born.

Some of the tribal elders who were still alive in the 1970s were considered knowledgeable about the language, but it is not certain what level of proficiency they had. During these trips, I was introduced to both Julie Olds and David Costa, whom I would come to know very well. They would become integral to the language revitalization efforts of not only my family but of the whole Miami Tribe community.

Around the same time that I learned that the last speakers of our language had been lost, Karen and I were making a huge transition in our lives. I had been contemplating the idea of pursuing a degree, but the whole idea was a pretty scary one. Our first child had just turned one year old and another was on the way. The odds seemed stacked against us, and a handful of naysayers let us know what they thought, but we decided to take the leap and rearrange our lives so that I could go to college. This meant that we both had to leave our current jobs of nearly ten years, mine in construction and hers in teaching. We sold most of what we owned and moved to southern Ohio, where I studied environmental science at Hocking College. The two years there were critical for me to build my confidence.

Eventually, I settled into the rigors of college, so we made yet another major transition, by moving our young and growing family to Missoula, Montana, where I enrolled in the wildlife biology program at the University of Montana. At the time, I was really interested in how tribes were developing environmental departments and wanted to pursue that as a new career. After graduating with my undergraduate degree in 1996, I wanted to continue studying wildlife biology but was not accepted into the graduate program. Regardless of this setback, I wanted to continue with graduate-level studies.

During this time, I was communicating with an elder from Indiana, who encouraged me to continue working with the language. Lora Siders, who passed away in 2000, knew Karen and I were already trying to incorporate the language in our home with our kids.

During one of our phone calls, when I shared with her that I didn’t get into graduate school, she said, “You know, you seem to have a love for the language, have you ever thought about studying the language?”

As it happened, I had become familiar with a faculty member on campus named Anthony Mattina, a well-known Salishan linguist. After talking with Lora, I took a chance and walked into Mattina’s office and asked, “Tony, this is a long shot, but what do you think about me doing linguistic research at the master’s level?” To which he replied, “When do you want to start?”

I said, “How about in two weeks when the next semester starts?”

He assured me he’d go to bat for me and see what he could do. With his support, I got into the linguistics program. From there, my whole direction in life shifted. I didn’t realize it, but I was being catapulted into the undeveloped and largely undefined field of Indigenous language revitalization, which would become my life’s pursuit.

The linguistics program at the University of Montana was great for me. I absolutely loved linguistics. The training significantly aided our home-learning efforts and would lay a foundation for me to support future language development at the community level. But, as I have learned over the years, while linguistics is important to reclamation work, it takes more than a degree in linguistics to revitalize a language.

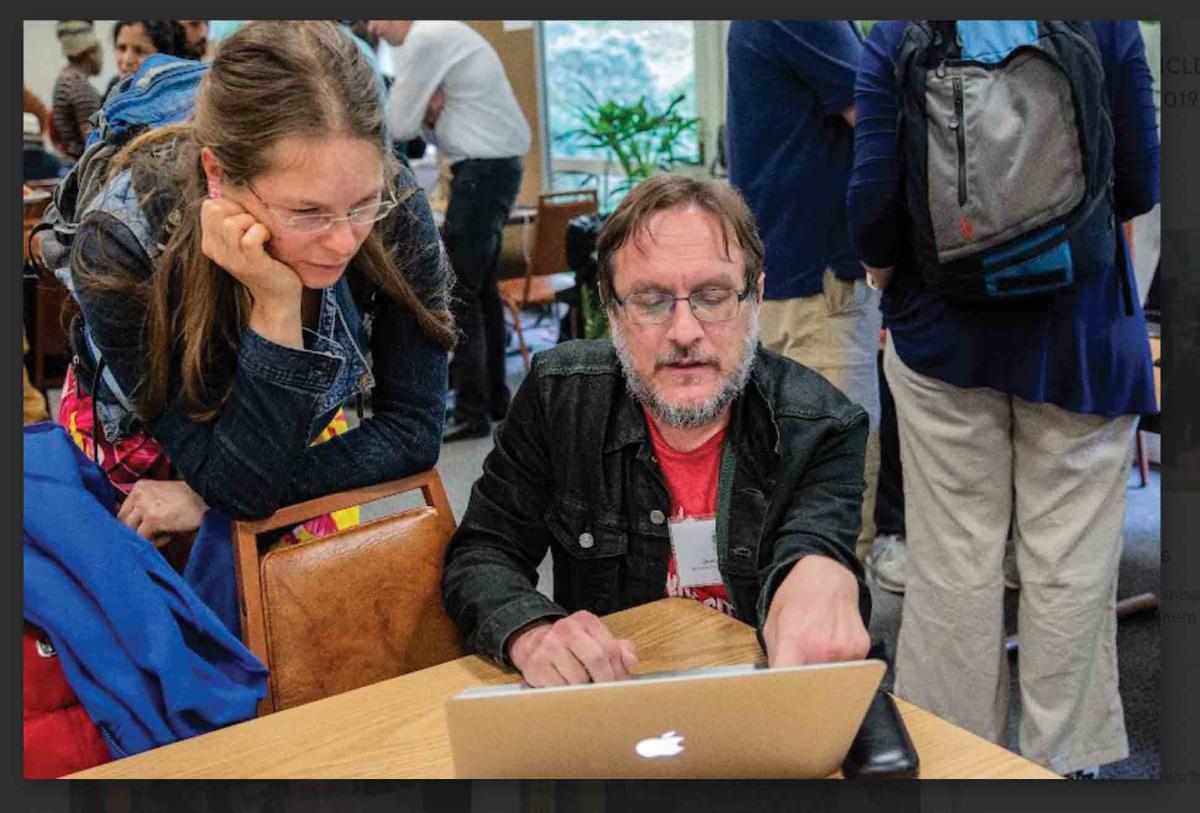

As my training advanced, I began to better understand grammar and other features of my language. I also began communicating more regularly with David Costa, who was reconstructing the grammar of the Myaamia language as part of his dissertation research at the University of California, Berkeley.

At home, Karen and I created learning aids and developed a home vocabulary to use with the children. Obviously, at this stage, the children were learning alongside us as parents. As we worked hard to develop enough vocabulary to stay in the language, it was still very topic-oriented. For the daily activities of preparing meals and taking care of the house, it was fairly easy to develop vocabulary. When the kids would slip back into English, we would pull them back into the Myaamia language by simply saying, “taaniši iilweenki” or “How is that said?” This, along with many other techniques, is how we encouraged staying in the language. We stayed in Missoula for six years, which allowed us to focus on our home efforts.

In 1996, as I was nearing the end of my coursework in linguistics, Karen and I began thinking about our next move. During the last couple of years, I had been in touch with Julie Olds. Julie is a tribal citizen who moved from Kansas City to Miami, Oklahoma, in the 1990s to be closer to the tribal community. She eventually ran for a tribal leadership position and, as she re-engaged with her tribe, she developed a strong interest in the language. In 1996, she was hired as the tribe’s language clerk, a position funded through an Administration for Native American Language grant. When I told Julie that I needed to find work, she said, “Hey, we’re hiring an environmental director. You want to come down to Oklahoma?”

I eagerly accepted and all five of us (yes, another child was born there somewhere) moved from Montana to Oklahoma, so I could take that position. My wildlife biology degree had come in handy after all. While I was working in the environmental department for the tribe, Julie and I began experimenting with some language programming for the local community, including a couple of evening programs. David Costa continued to consult with us, and, in that same year, he produced the first-ever student dictionary of the Myaamia language, which the community was very excited about. These were our first attempts to introduce language programming into the community. I began to experience the differences of community work and its challenges. Working with the community on language revitalization was different from what Karen and I were doing at home. Different in that we had more control over the language-learning environment in the home. In a community setting, you don’t have that much control over the level of engagement of your learners and what language they may fall back into after they are away from the learning environment.

At this time, there was little funding to support language revitalization at the community level. And no funding meant no jobs. A few years later, in 1999, I completed my master’s thesis on the Myaamia language remotely from Oklahoma and then left my position with the tribe to accept a position with a museum near West Lafayette, Indiana. The Museums at Prophetstown is where my family and I landed with the promise of launching language programs in the Myaamia historical homelands. After a couple of years, however, the museum opportunity began to collapse, which happened just as my fourth and final child was born. Karen and I found ourselves stuck again with few prospects.

If ever we had hit a low in our lives, this was it. After eight years of schooling, two moves, and several attempts to create community language programming, the pressures of family life with little income were weighing heavily on me. I began thinking I needed to abandon the community language efforts and get a real job to support my growing family.

In spring 2001, I called Julie yet again and said: “I can’t do this anymore.”

After a very difficult discussion, Julie said, “Well, I’ve got one more idea. Let’s call Miami University and see if something might be possible.”

Starting in the early 1970s, the Miami Tribe had begun working with Miami University of Ohio. This had resulted in a scholarship program for Miami Tribe citizens to attend the university.

I remember saying, “You go, sister, but I can’t continue doing this.” I just couldn’t imagine that a major university would consider supporting a language-revitalization effort that had no direct connection to any campus degree program. That said, you never really know what’s around the corner, what door is going to open, and whether or not you should step through it. Life is full of uncertainty, risk, and challenge.

To my shock, Miami University was willing to explore the possibility of supporting the Miami Tribe’s language interest. After negotiations between officials at Miami University and leaders of the Miami Tribe, the university came back with a commitment to fund one position for three years and call it the Myaamia Project. In university language, a project means something unofficial, so the future for this new venture was uncertain. Officials agreed to revisit the newly formed Myaamia Project at the end of three years to see if it was worthy of continuation. Miami University’s commitment included one salary position for a director, and the Miami Tribe asked that I serve as the director of the new project. It would be the first time since leaving my career in construction in 1991 that I had a decent salary with benefits.

Once more we moved, this time from near Lafayette, Indiana, to a town near Oxford, Ohio, where Miami’s campus is located. My wife and I were both tired and now raising four children. She told me that she never wanted to move again. “Make it work!” she said. And so, in April of 2001, we made one more attempt to make something stick, all while continuing our language efforts in the home.

Today the Myaamia Center (previously Myaamia Project) is 23 years old with 20 full- and part-time staff. Over one hundred Myaamia people have graduated from Miami University and nearly 50 Myaamia students are attending the university today. The partnership between the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma and Miami University is founded on respect and trust. The Myaamia Center is tribally directed, to ensure that the interests of the tribal community are always front and center in our collective efforts.

Within the community, the language and cultural revitalization effort is known as myaamiaki eemamwiciki, “the Myaamia awakening.” There is now a new generation of children growing up in the community who never knew a time when the Myaamia language was not present in their lives. The level of growth and development is astounding to me as I think back to our simple beginning. David Costa is the director of our Language Research Office and Julie Olds serves as cultural resources officer for the Miami Tribe. The three of us may have been catalysts in a process none of us could have planned, but today there is an energy and commitment that exceeds us.

David, Julie, and I came into this world in 1962. Julie and I were part of a generation born into a vacuum of loss in our families and tribal community. In the ashes left from all the horrific destruction caused by colonization we found embers that would rekindle into flames of language and cultural revitalization and make possible the new cultural bounty we enjoy today.

In the absence of language speakers, archival documentation has been the core of our effort. We created our own means of finding language documentation, processing archival content, and weaving what we would learn from those materials back into our homes and, eventually, the community. The entire process was driven by a need to pursue that which strengthened us and made us feel whole again. A journey of healing that not only reconnected us to each other as a community but to our ancestors, who were thoughtful enough to leave behind this evidence of how they thought and spoke.

Thirty years ago, I believed that learning my heritage language would help me reconnect to a part of myself that I valued. Although I had no way of knowing if I was correct in that belief, my personal journey provided more than I ever thought possible. I find myself thinking about what it is I learned from all of this, and it boils down to a simple observation. Even a little bit of language can significantly influence a child’s identity formation in relation to who they are as a Myaamia person. Family, community, language, and culture all factor into strengthening a healthy connection to others who share the same experience and interpretation of place in life. But now, as I watch my own grandchildren born into this space of revitalization, I realize that this is the generation that will not have known a time when myaamiaataweenki, the Myaamia language, was not spoken. I wonder how it will be different for them, and I look forward to learning from their experiences. I often think about how difficult it was for our ancestors to experience loss in the way they did. I am grateful for what they preserved for us, for the relationships I established through this effort, and for being alive at a time when we can rekindle that spirit of our people for a more prosperous future.