When humorist Will Rogers died in a plane crash in Alaska in 1935, millions around the world mourned his passing. For V. V. McNitt, Rogers’s death was a practical as well as a personal loss. McNitt managed the McNaught Syndicate, which distributed Rogers’s highly popular column to newspapers across America. What would McNitt do now without his star writer?

He thought he’d found a replacement with Alice Roosevelt Longworth, the sharp-tongued daughter of the late President Theodore Roosevelt. In short order, her new feature, “What Alice Thinks,” was in 75 newspapers, a seemingly auspicious beginning.

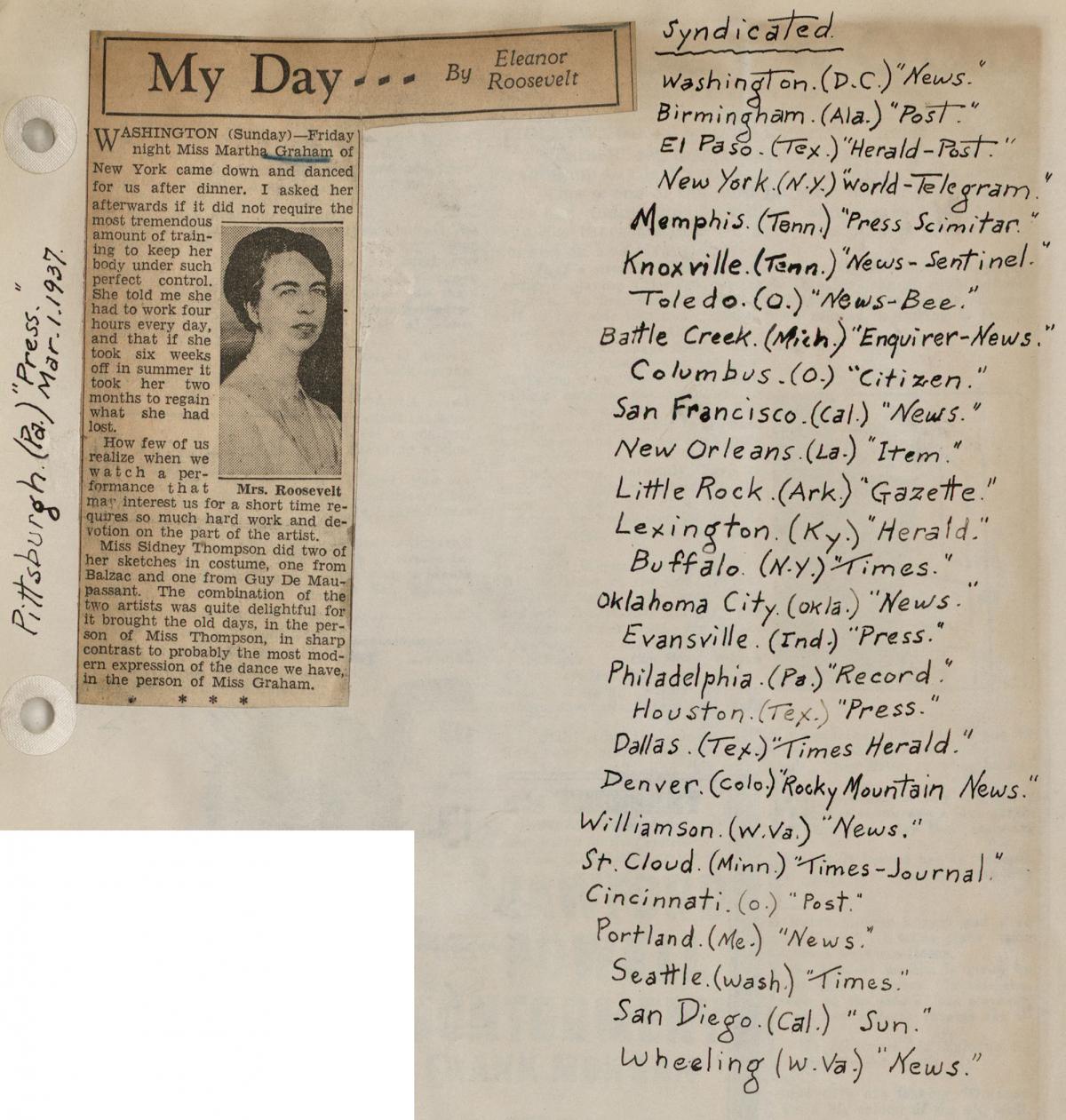

Then a rival company, United Feature Syndicate, recruited First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to compete with her cousin. Longworth’s column quickly fizzled, and ER would go on to write her column, “My Day,” six days a week for nearly 30 years.

“My Day” far outlasted Eleanor’s time in the White House, ending only with her death in 1962. The sheer frequency of “My Day,” which ran with very few interruptions during its decades of publication, also extended ER’s influence immeasurably. She would become an almost daily presence in the lives of her audience in a manner that anticipated the social-media age.

When Roosevelt’s name was floated as a possible vice-presidential running mate for President Harry Truman in 1948, she demurred. “As an elected or appointed official,” biographer David Michaelis notes, “she would have felt that any office was a demotion or a constraint. Now free to speak her mind, she was uniquely influential because her audience was listening. Through her column she could give her opinion on matters six days a week. Firmly, unscoldingly she was there each day to remind people that a powerful America was supposed to be above racism, had a responsibility to find ways to give basic decencies to the poor.”

Roosevelt shattered many precedents in her time as first lady from 1933 to 1945. As the wife of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, she was the first first lady to drive her own car, travel by plane alone, and hold her own press conferences. Though from a wealthy family, Eleanor also insisted on earning her own money through speeches, radio appearances, and her writing, which included books and magazine and newspaper articles.

Her work as a newspaper columnist invites obvious ethical questions. In routinely using her column to promote a presidential administration in which she also had a key role, ER was clearly playing both sides of the fence. Critics also accused her of using her media gigs to financially profit from her role as first lady.

Roosevelt shrugged off the complaints, suggesting that, regardless of her White House duties, she’d be writing and speaking, anyway. “I did both before my husband became the President,” she wrote in a 1938 column, “and I hope I shall continue to do so after he ceases to be President. I have no illusions about being a great speaker or a great writer, but I think in some of us there is an urge to do certain things, and if we did not do them, we would feel that we were not doing the job which we had been given opportunities and talents to do.”

ER also defused criticism by donating much of her money to favored causes. Her earnings usually exceeded FDR’s presidential salary.

“If she made hundreds of dollars per broadcast and thousands per lecture, and many more thousands for her daily column,” writes biographer Blanche Wiesen Cook, “only Republicans chafed—especially when they learned that she gave virtually every dollar she made away to causes she believed in, through the American Friends Service Committee.”

Roosevelt’s modesty about her writing skills also served to lower expectations. She wasn’t often considered, even by many of her admirers, a memorable literary stylist.

“There were no grace notes or obvious influences,” Michaelis observes of her prose. “‘My Day’ was not writing for effect, or to be remembered; it was to get something done.”

“She was no writer; her prose style was pedestrian and awkward,” Hazel Rowley declares in a generally flattering book about Eleanor and FDR. “She was no intellectual; the ‘My Day’ column would contain plenty of platitudes. But in the long run these things did not matter. She was a great communicator with a beguiling fireside quality that she shared with her husband.”

Eleanor’s first “My Day” column was, literally, a fireside chat. Here’s the opening passage from her debut on December 30, 1935:

I wonder if anyone else glories in cold and snow without and an open fire within and the luxury of a tray of food all by one’s self in one’s room. I realize that it sounds extremely selfish and a little odd to look upon such an occasion as festive. Nevertheless, Saturday night was a festive occasion, for I spent it that way.

The house was full of young people, my husband had a cold and was in bed with milk toast for his supper, so I said a polite good night to everyone at 7:30, closed my door, lit my fire and settled down to a nice long evening by myself. I read things which I had had in my briefcase for weeks. . . . I went to sleep at 10:30.

To read such a passage is to wonder if Roosevelt was a better writer than even her champions knew. At first glance, it seems little more than a homely reflection on the coziness of a winter hearth. But the essay, like its writer, points to a presence more complicated than its surface.

There is, for starters, the subversive declaration by the wife of the most famous politician in the world that what she really enjoys is being alone. It’s not a sentiment that was often openly voiced by a public figure in 1935—nor, for that matter, is it something many of today’s celebrities would candidly admit.

Also vivid is that passing reference to “my husband,” which would become a favorite euphemism in “My Day” for the president. This was a time when chief executives were routinely hailed as minor deities. Yet in this first column, as in countless ones to follow, ER has slyly cut the commander-in-chief down to size. In her telling, the leader of the free world is also a man who gets colds like the rest of us, in bed early on a Saturday night.

A glamorous picture of White House life, this is not. One might assume that ER’s vignette is a calculated study in populism, assuring Americans that the Roosevelts were, at base, pretty much like everyone else.

Yet small details, surely obvious to ER when she included them, argue otherwise. The first lady delights in a tray of food in her own room, and her readers surely know that she didn’t fetch that tray herself. She has servants to bring her dinner during a global depression leaving many citizens hungry.

That’s the thing about the “My Day” columns; they express the life of a woman who doesn’t seem to be making herself larger or smaller than she really is. Their candor captures a quality often evoked in our present-day culture but seldom realized: authenticity.

If FDR exemplified the heroic presidency as a champion of the New Deal and wartime leader on a global stage, then his wife tended to offer an alternative vision. Her columns suggested that presidents and first ladies, for all the trappings of high office, still lead much of their lives in the lowercase. They get tired. They get sick. They sometimes don’t want to be bothered.

Time magazine, commenting on “My Day,” lauded “Mrs. Roosevelt’s ability to make the nation’s most exalted household seem like anybody else’s.”

The sheer dailiness of so many of its doings made “My Day” a fixture of national life. E. B. White paid it a wry homage in 1941 when he titled one of his Harper’s Magazine essays “My Day,” then offered an account of his farm chores and chats with neighbors. Though White was a far better writer than Eleanor Roosevelt, he came to understand, as she did, that the domestic concerns of his writing were a respite for his harried readers. “To the prisoners of newspapers where wars are always raging,” Mary Marshall told readers of The Nation in 1938, “‘My Day’ is like a sunny square where children and aunts and grandmothers go about their trivial but absorbing pursuits and security reigns. In the sense of security it generates lies the deepest appeal of ‘My Day.’’’

As White and Roosevelt also grasped, successful writing usually requires a great deal of work to make it seem effortless and casual. “My Day,” for all its illusion of a few lines dashed off like a friendly note, was often a pain to get to press.

Although the words of “My Day” were Roosevelt’s own, she typically dictated her column to longtime assistant Malvina “Tommy” Thompson. Because ER’s schedule as first lady was crammed, she often didn’t get around to composing the column until midnight approached. Eleanor’s daughter, Anna, once parted a curtain on the “My Day” production line: “I used to cringe sometimes when I’d hear Mother at eleven thirty at night say to (Thompson), ‘I’ve still got a column to do.’ And this weary, weary woman would sit down at a typewriter and Mother would dictate to her. And both of them so tired.”

That sense of vulnerability informed the column, which is what often made it seem so real. Eleanor’s high-pitched speaking voice could frequently irritate listeners. When she decided to take lessons to improve it, she wrote about her challenge in “My Day” with a frankness unusual for the times. “It seems stupid,” she told readers, “not to have done this before. . . . One must take advantage of anything which can make life easier for oneself and pleasanter for other people.”

When the king and queen of England made a visit to the U.S. in 1939, a dinner at the Roosevelts’ Hyde Park estate nearly went off the rails when a huge assortment of china crashed to the floor. Sara Roosevelt, FDR’s mother, wanted the embarrassing mishap kept secret, but Eleanor wrote about it in “My Day” as a way to tell hostesses everywhere that in spite of the best laid plans, such things happen. ER also addressed the minor scandal she had caused by serving hot dogs to the royals at a family picnic. Roosevelt wondered what all the fuss was about. “I am afraid it is a case of not being able to please everybody,” she wrote, “so we will try just to please our guests.”

Roosevelt revealed much of herself in her column, but, like most writers, she didn’t discuss everything. Lorena Hickok, a former journalist who had encouraged ER to write the column, was impressed by the charm of Roosevelt’s letters and thought her conversational style could be adapted into the kind of feature that “My Day” became. Some of the many letters the women exchanged suggest they shared physical intimacy, pointing to a more complicated family life than the one portrayed in Roosevelt’s public writings. FDR’s extramarital relationships were obviously not “My Day” material, either.

Elliott Roosevelt, writing a decade after his mother’s death, argued that the woman of the “My Day” columns was just one version of their author. “She pictured herself as a calm, contented woman deeply concerned with the world and her family. . . . Only deep below the surface of her careful prose could be found an occasional clue to her conflicts.”

Perhaps a talent for knowing what to say—and what to keep unsaid—is the mark of a natural politician, which Eleanor Roosevelt surely was. It’s one reason her column remained popular even after she was widowed and no longer in the White House.

Her “My Day” column was renewed after FDR died, but with a provision that it would be dropped if it were no longer viable for her syndicate. “Strangely,” writes Rowley, “it would prove more successful than ever. Eleanor Roosevelt’s columns carried the whiff of a more heroic age in American history—an age when the whole of the free world looked to the White House for reassurance and inspiration.”

Roosevelt maintained a high profile early in her widowhood as an official at the fledgling United Nations. She later worked as a volunteer supporter of the U.N. and in many civic and Democratic party causes.

Beyond their quaint domestic observations, her “My Day” columns could also be boldly political, especially after she returned to life as a private citizen and felt at even greater liberty to speak her mind.

The concerns she voiced remain an enduring part of the national conversation. In 1959, when a Long Island tennis club refused to let the son of prominent African-American diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ralph Bunche become a member, Roosevelt vented her displeasure. “How can we in the North ask of the South the sacrifices that we are now asking if we countenance this kind of snobbish discrimination?” she asked. “If you can’t play tennis with Negroes, how come you are willing to let them be drafted into your army and die for you? I am ashamed for my white people. I am one of them, and their stupidity and cruelty make me cringe.”

Many of Roosevelt’s “My Day” columns can be read online, and they’ve also been curated in several books, such as editor David Emblidge’s My Day: The Best of Eleanor Roosevelt’s Acclaimed Newspaper Columns, 1936–1962.

They’re written with a simplicity that ER’s critics found banal and her fans found appealing. Stella Hershan, who fled Nazi-occupied Austria and arrived in the United States penniless, learned about her new country by reading “My Day.”

“Her writing was so simple, even I could understand it. From her,” Hershan said of Eleanor Roosevelt, “I learned about America.”

More than half a century after her death, Roosevelt’s “My Day” columns are a continuing instruction in the privileges and obligations of life in a free republic.

Shortly after her husband’s death in 1945, Eleanor Roosevelt offered a few words in her column about the power of civil discourse. What she said aptly summarized how she wrote—and how she lived:

Of one thing I am sure: Young or old, in order to be useful we must stand for the things we feel are right, and we must work for those things wherever we find ourselves. It does very little good to believe something unless you tell your friends and associates of your beliefs. Those who fight down in the marketplace are bound to be confused every now and then. Sometimes they will be deceived, and sometimes the dirt that they touch will cling to them. But if their hearts are pure and their purposes are unswerving, they will win through to the end of their mission on earth, untarnished.