On April 8, 1892, the Boston Evening Transcript published an unusual letter to the editor. Tucked near the bottom of the page between a Washington gossip column and a literary chronicle, the writer of the short note, titled “Perilous Stuff,” warns his fellow readers about a piece of fiction he recently encountered in a local magazine. “It is a sad story of a young wife passing through the gradations from slight mental derangement to raving lunacy,” he writes. “It is graphically told, in a somewhat sensational style, which makes it difficult to lay it aside, after the first glance, till it is finished, holding the reader in morbid fascination to the end. It certainly seems open to serious question if such literature should be permitted in print.”

The letter writer was not the only one disturbed by “The Yellow Wall-Paper.” More than a year earlier, the editor of the Atlantic Monthly refused to run the story in his own publication. He had written a curt reply to its author:

Dear Madam,

Mr. Howells has handed me this story. I could not forgive

myself if I made others as miserable as I have made myself!Sincerely yours,

H. E. Scudder

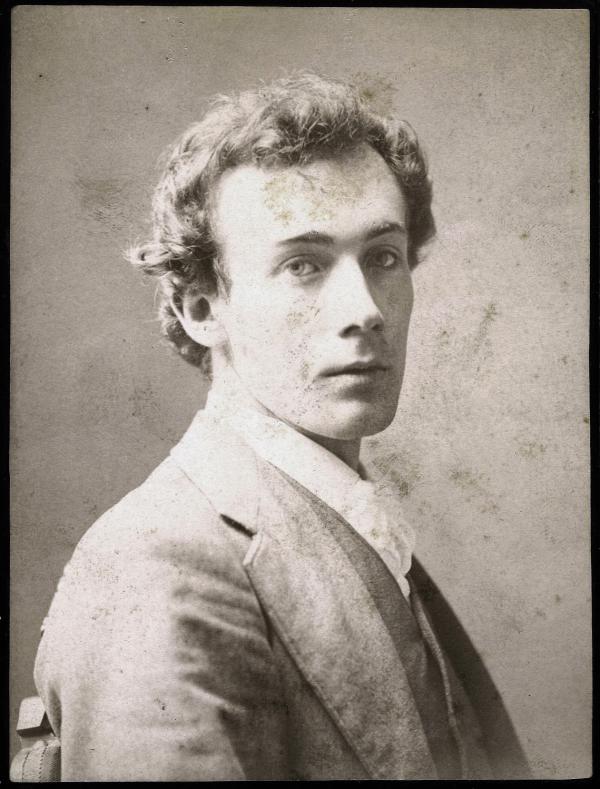

Even by the standards of rejection letters, it was a brutal note. When Charlotte Perkins Stetson, a thirty-year-old single mother living in Pasadena, received Scudder’s response, however, she shrugged it off. She was not a woman who was easily discouraged, perhaps because she had experienced worse things in her relatively short life. “This was funny,” she would later write. “The story was meant to be dreadful, and succeeded.”

If you were an undergraduate English major, or if you were ever required to read an anthology of American literature, there’s a good chance that you came across “The Yellow Wall-Paper” at some point. The protagonist, a new mother suffering from what would now likely be considered postpartum depression, is taken on a country vacation to recover from her “nervous troubles.” Ordered not to overexert herself by her physician husband, prohibited from writing or socializing with company, and deprived of any sort of mental stimulation, she becomes increasingly obsessed with the patterns in the lurid yellow wallpaper of her bedroom. As the days pass, she eventually descends into madness.

The gothic story, with its unsettling and ambiguous ending, has become a classic of feminist literature. It is also autobiographical—a fictionalized account of the debilitating depression that Stetson (better known by her second husband’s last name, Gilman) experienced after the birth of her daughter, Katharine, a time when, she said, she “came so near the border line of utter mental ruin that I could see over.”

In the years since “The Yellow Wall-Paper” was rediscovered by critics in the 1970s, the story has drawn in readers who have offered up their theories about its possible meaning. “The Yellow Wall-Paper” is a protest against the patriarchy, against the suffocating domesticity of motherhood and marriage. “The Yellow Wall-Paper” serves as a critique of yellow journalism. “The Yellow Wall-Paper” reads as an indictment of industrial capitalism. (Author Jennifer Lunden has noted that wallpaper of the era frequently contained arsenic capable of forming a toxic gas that could sicken oblivious women while they decorated their homes.)

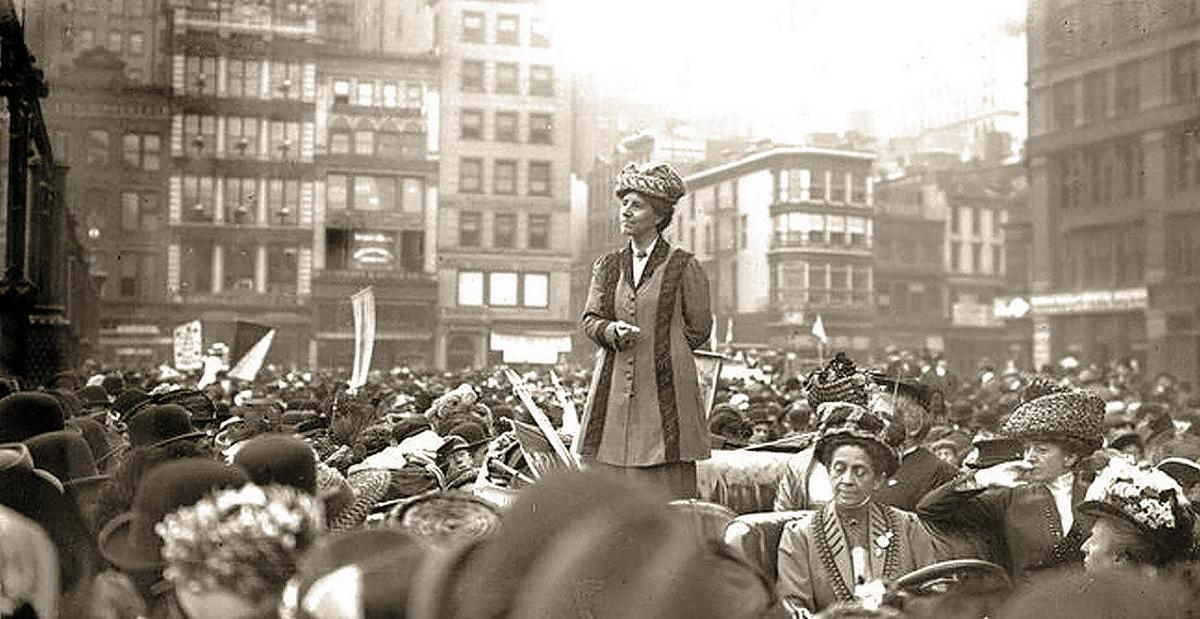

If “The Yellow Wall-Paper” evokes “morbid fascination,” if it holds the reader uncomfortably against his will, its author has made a fainter impression on readers outside of the scholarly community. In her heyday around the turn of the twentieth century, Gilman was a prominent voice in the women’s suffrage movement, a social activist, and an internationally read author whose work was translated into several languages. (It didn’t hurt that she was related on her father’s side to the famous Beechers of New England, great granddaughter of the renowned preacher Lyman Beecher, and grandniece of the author Harriet Beecher Stowe.) She is also the author of a prodigious body of work, as a new collection released in August by the Library of America shows. The volume weighs in at more than 900 pages, and it does not include Gilman’s articles or nonfiction. But while the names of Gilman contemporaries like Susan B. Anthony and Jane Addams remain well known, a reference to Charlotte Perkins Gilman usually elicits a vague squint. It’s a name you know you should know, the squint says, but the details are hazy—or perhaps you never knew them at all.

The details go like this: In 1888, with two train tickets and ten dollars in her pocket, Gilman set out to cross the country with three-year-old Katharine, accompanied by her friend Grace Ellery Channing. Gilman was on her way to California and leaving her husband, Charles Walter Stetson, behind in Rhode Island. Gilman was resolved to escape the marriage she believed to be the source of her deteriorating mental state. She saw it as a matter of survival, a stark choice, as she put it, “between going, sane, and staying, insane.”

In Pasadena, Gilman cobbled together what she would later refer to as her “professional ‘living.’” She taught drawing to children and wrote articles and poems that she sold for a few dollars each—or gave away—to progressive papers in her newly adopted hometown. There were two political causes, in particular, that offered Gilman “a platform for her talents,” her biographer Cynthia Davis writes. One was the women’s movement, an interest that “drew upon her own difficult experiences.” The other was nationalism—like many intellectuals at the time, Gilman was entranced by Edward Bellamy’s socialist utopian novel, Looking Backward—and it was the latter that allowed her to “experience her first taste of fame.” She possessed a knack for setting polemic into pithy rhymes that caught the attention of those who shared her political views:

Said the Socialist to the Suffragist:

“My cause is greater than yours!

You only work for a Special Class,

We for the gain of the General Mass,

Which every good ensures!”

Her writing began to gain her recognition, and she received fan mail from the novelist (and fellow Bellamy enthusiast) William Dean Howells, among others, along with invitations to lecture at women’s clubs around Pasadena.

In 1891, at a meeting of the Pacific Coast Women’s Press Association, Gilman met and fell in love with a fellow writer named Adeline Knapp (one of several women she would have romantic relationships with during her life). Later that year she moved with Katharine to Oakland to live with Knapp and run a boarding house while she worked to advance her literary career. The new freedom and her growing reputation likely felt exhilarating, but they did not make Gilman’s life easy. In fact, Davis writes, Gilman would remember her years in California as some of the most difficult in her life.

Just as many writers before her, Gilman soon learned that literary fame did not guarantee financial success. (She noted that she never received “a cent” for her most famous short story when it finally appeared in the New England Magazine.) Nor did it liberate her from the domestic obligations she despised, responsibilities that only increased when Gilman took in her mother, who was suffering from breast cancer. In Oakland, Gilman churned out pages tirelessly. She was also raising her daughter, tending to her terminally ill mother, and nursing several ailing residents who lived in the boarding house she was running in her spare time. The relentless demands of caretaking must have made her feel as though she were bailing out a sinking boat with her two bare hands. “I did all the housework and nursed mother till I broke down,” she recalled later. “Then I hired a cook and did the nursing till I broke down; then I hired a nurse and did the cooking till I broke down.”

“Broke down” was not an exaggeration. Gilman frequently suffered from periods of what she referred to as “humiliating weakness,” dark stretches of days or weeks when she found herself unable to write a single sentence, read her correspondence, or make even basic decisions. Lunden has speculated that Gilman’s neurasthenia may have been a version of an illness of the times similar to chronic fatigue syndrome, although Gilman, an athletic woman who relished exercise and took pride in her feats of strength, insisted that the problem was mental and not physical. “A sympathetic lady once remarked, ‘Yes, it is a sad thing to see a strong mind in a weak body,’” she wrote in her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. “Whereat I promptly picked her up and carried her around the room. ‘Please understand,’ said I, ‘that what ails me is a weak mind in a strong body.’”

Gilman’s “weak” mind possessed an analytical bent. Late in her life, she would crunch the numbers and calculate that she had lost a total of 27 years of working time due to her depressive episodes. If we take her at her word, this makes her achievements all the more impressive. After a lengthy struggle to legally end her marriage to Stetson—a saga that was covered in excruciating, gleeful detail by the press—Gilman’s petition for divorce was granted in 1894. She had been publicly ridiculed, and her unfeminine career aspirations made her the subject of an article in the San Francisco Examiner titled “The Wife and the Writer: Should Literary Women Be Addicted to the Marriage Habit?” Gilman, in fact, had soured not just on marriage but on relationships altogether. Her arrangement with Knapp had ended badly, and the following year she scraped together enough money to escape from California and spend several months with Jane Addams at Hull-House. She had left behind debts she would struggle to repay and a tarnished reputation, but in Chicago, Gilman felt herself to be among kindred spirits, “distinguished people” and “humanitarian thinkers” like the famous sociologist Lester Ward and writers H. G. Wells and George Herron.

Hull-House may have seemed like the ideal place for a passionate, aspiring reformer like Gilman, but it quickly became clear that she was not suited for a quiet life, selflessly ministering to the poor. The mundane realities of dealing with poverty were less compelling—and less pleasant—than grappling with societal failings on an intellectual level, Davis observes. As her famous grandfather did, Gilman possessed a preacher’s heart; she wanted to call out the world’s injustices and its “many needless evils.” She left Hull-House with a new determination to refocus her literary ambitions on the sociological issues of the day.

For the next several years, she remained “at large,” writing and preaching as she traveled across the United States. (She would eventually address audiences in all but four states.) Gilman was a natural public speaker, one who could deliver her talks without notes, offer deft retorts to her hecklers, and think on her feet. While speaking at one outdoor event, she inhaled a fly, and, rather than ruin the conclusion of her talk, she reported that she “calmly swallowed it, and finished in fine style.” For her efforts, she often received enough money to cover only her travel expenses. “Will they pay you?” a friend asked before one trip, and when Gilman replied that she didn’t know, the friend exclaimed, “Don’t know—isn’t that your business?” Gilman may have liked to cultivate the image that she lived “as propertyless and as desireless as a Buddhist priest,” but, in reality, Davis says, money was “a constant preoccupation.” She may have been saving the world, but she still had bills to pay, including the outstanding debts that lingered back in California.

In 1896, she accepted an invitation from Susan B. Anthony to attend the National American Woman Suffrage Association convention in Washington, D.C., where a case of the mumps did not prevent her from speaking or addressing the House Judiciary Committee on the subject of suffrage. Her attendance was a triumph. She was honing the arguments she made in her speeches, preparing a draft of her most famous work of nonfiction, Women and Economics: A Study of the Economic Relation Between Men and Women as a Factor in Social Evolution (1898), which she would eventually pour out onto the page in an exuberant rush. The book, which argued that women’s economic dependence on men—the “sexuo-economic relation” Gilman called it—was the true cause of women’s problems, was the first in-depth work written by a woman to delve into the economic role of women’s domestic work. It was hailed by the suffragist leader Carrie Chapman Catt as “utterly revolutionizing the attitude of mind in the entire country, indeed of other countries, as to woman’s place.” The book would once again fail to make her money, but it catapulted her into the limelight, where she received both criticism and acclaim. (When she attended one dinner in 1899, the guest of honor, William Jennings Bryan, gave up his seat for her.) Her “radical views,” Davis says, made her “a prophet to some, impractical to others, and ‘perfectly horrid’ to a good many.”

They were heady times for Gilman, but they came—as success so often seems to—with a catch. The demands of life as a writer and public intellectual—the grueling travel schedule, the long hours spent hunched over a desk, working in solitude—were made easier by the fact that Gilman spent much of her time alone, accountable to no one but herself. Following the divorce, she had sent Katharine, then nine years old, back to Rhode Island to live with Stetson, who had recently married Gilman’s friend Grace. The shared custody arrangement was a sensible one for many reasons. But the intense public censure Gilman received for abandoning her child had left her defensive and deeply wounded. The accusations that she was a heartless woman who had sacrificed her child for the sake of her career played into her own ambivalence and her guilt about Katharine, painful feelings that haunted her, no matter how much she attempted to rationalize them away.

It is surprising then—or perhaps not—that the next book this “unnatural” mother published focused on childhood development and childrearing. By the time Concerning Children (1900) was released, Gilman was back to living at a fixed address in New York City, and she had once again assumed the outward trappings of a conventional feminine life. A decades-long correspondence with her younger cousin, George Houghton Gilman, had kindled into romance, and in June of that year, the two were married. Katharine had come to New York to once again live full-time with her mother. Concerning Children—which was dedicated to Katharine—included some bold proposals on how to restructure the nuclear family and advocated for the professionalization of early childhood education. What it did not do anywhere in its nearly 300 pages was touch on Gilman’s own joys or difficulties as a mother. The book’s authoritative tone projected confidence and not a single trace of the anguish she once expressed in a letter to Katharine’s “co-mother,” Grace:

This won’t do. I can’t afford to ache. Dear, I think if you could see how patiently I try to carry my patched and cracked and leaky vessel of life—how I pray endlessly for strength to do my work! . . . , to hold the attitude and do the things which to me seem right, how I have truly and fully accepted the not-having—O well, there!—We all do what we can.

What she could do was work. In 1909, just shy of her fiftieth birthday, Gilman turned her attention to her most ambitious project yet, The Forerunner, a progressive, prosuffrage monthly magazine that would delve into what she considered the “personal and public problems” of the day. Each issue contained at least one poem, a short story, and a section from two longer serialized works, one fiction and one nonfiction. Gilman wrote everything that appeared in the publication, along with advertisements for products that she used and personally endorsed. On the back of her magazine’s no-nonsense cover, she stated its purpose: to “stimulate thought; to arouse hope, courage and impatience; to offer practical suggestions and solutions.”

Several critics have pointed to The Forerunner as one of Gilman’s greatest achievements. The magazine gave her the freedom to cover whatever controversial issues she saw fit and a platform where she could spar, in print, with fellow intellectuals, such as the Swedish feminist Ellen Key and the famous journalist Ida Tarbell. It also offered the independent Gilman—who had sometimes clashed with her editors at other publications—uncontested control of everything that appeared in The Forerunner’s pages.

But editors, most writers will grudgingly admit, do serve a useful purpose. With no oversight, tight deadlines, and little time for revisions, The Forerunner’s focus was narrow, and its creative work was frequently uneven. Gilman, middle-aged, had decades of writing behind her. She was now more concerned with arguments than she was with aesthetics and no longer seemed interested in conjuring up the kind of evocative power that had made the “The Yellow Wall-Paper” so “dreadful” and ultimately such a success. She now cared, Davis says, “more about her works doing good than being good.”

More problematic for The Forerunner than creaky plots and wooden dialog is the work it contains that endorses eugenics, including a 1911 fictional work titled The Crux. The novel, which “promot[es] the reestablishment of white supremacy on the frontier,” reflects a darker strain that runs through Gilman’s ideas about society’s progress—beliefs that would deepen as she aged and later complicate perceptions of her work and her legacy.

For contemporary readers, the racist pseudoscience of eugenics is difficult to reconcile with many of Gilman’s otherwise enlightened ideas. But Gilman, unfortunately, was not alone in embracing this “new science.” Scholars such as Dana Seitler have pointed out that many white suffragists supported the eugenics movement in the early twentieth century, a time before many of its theories had been discredited and when even elite universities such as Harvard were teaching eugenics in their classrooms.

For Gilman in particular, eugenics seems to have held its own allure, one that aligned with how she wanted to see the world. Eugenics “helped her to hone her sense of what and who might best enable the collective to grow and thrive,” Davis writes. It offered a way to “expedite the journey from here to utopia.”

Utopias were always beckoning to Gilman, somewhere off in the distance, just out of reach, tantalizing and confounding her. In her novel Herland, which she published in The Forerunner in 1915, an isolated country inhabited by an elite race of women is discovered by three dumbfounded male explorers who cannot believe what they have found. Herland is idyllic. Its female citizens appear to have solved most of the technical and social problems that plague the rest of the known world, along with the messy emotional problems that are inevitably tangled up in love and family life. Only the fittest females who are worthy of motherhood bear children through parthenogenesis, a solitary process. The youngest Herlanders are tended to by professional care-givers while their birth mothers are free to pursue whatever work suits them best. These women are untroubled by guilt or the pangs of separation; they never waste time crying outside the day-care door. It seems everyone in Gilman’s utopia has either evolved past useless human feelings or else they are in possession of superhuman self-control.

This, more than anything, may be the true secret to Herland’s success, but how exactly it is achieved is just one of many questions that the book glides past. Gilman can’t give us an answer. “Mother love does not give human understanding,” she wrote in a 1913 essay. She could have been talking about herself.

Gilman had hoped that The Forerunner might bring in some money, perhaps enough for her and Houghton to purchase a house in the country, a place where she might find some relaxation and peace. It didn’t. Faced with dwindling funds, she published the final issue of The Forerunner in December of 1916. By that time, World War I was raging in Europe and the idea of “practical solutions” must have seemed deeply naïve and—like Gilman herself—increasingly the product of a bygone age.

With her fellow suffragists, Gilman celebrated the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1919, but as the years passed, Davis writes, “Her public finally tired of her.” Following a diagnosis of breast cancer and the death of Houghton, she moved back to live near Katharine, now married herself, in Pasadena—the same place where she had once launched her career and stirred up scandal. Gilman had witnessed her mother’s agonizing death from cancer. She had no illusions about what was in store for her, and she had no intention of surrendering on anybody’s terms but her own. She managed to create one final controversy when she committed suicide on August 17, 1935, after leaving a note that made her intentions clear. “I have preferred chloroform to cancer,” it read. She had followed the pragmatic advice that she had once given her readers many years ago. “Suffering remains to most of us,” she wrote, “and is to be borne by looking outside of and beyond it.”