On October 25, 2018, NEH Chairman Jon Parrish Peede spoke at the Governor’s Awards in the Humanities in Columbia, South Carolina. Below, a revised version of his remarks.

As humanists, we see our duty as not only preserving artifacts, or underwriting research, or presenting exhibitions and films, but as the nearly sacred duty of pointing the way for the next generation, so that they, too, can live meaningful, impactful, fulfilling lives.

Today, we honor four people who have taken this calling to heart: Anne Walker Cleveland, a dedicated educator and library supporter; Bobby Donaldson, a distinguished scholar and administrator; Sara June Goldstein, a champion of the literary arts; and Cecil J. Williams, a chronicler and truth-teller who spent a career behind the camera so that essential stories of the civil rights movement—and, indeed, our nation—will never again be obscured.

I am proud to be here with all of these honorees.

I am here out of respect for Randy Akers and his team at South Carolina Humanities. And there is another reason as well: Cecil J. Williams.

It is a rare gift in life when you get to publicly thank someone who took a chance on you when it really mattered.

Cecil took a chance on me.

When I was 25 years old, which was itself some 25 years ago, I acquired and edited Cecil’s foundational book on the modern South and the state of South Carolina, Freedom & Justice: Four Decades of the Civil Rights Struggle as Seen by a Black Photographer of the Deep South.

In many ways, it was a usual transaction: a potential book offered to a university press in a subject area where the press has experience. But, in other ways, the publication of Freedom & Justice continues to stand out.

I was less than a year into serving as an editor at Mercer University Press. I had not long been out of graduate school, where I studied under Bill Ferris—who was soon confirmed as NEH chairman—and where I studied under the brilliant Bob Brinkmeyer, who now directs the Institute for Southern Studies at the University of South Carolina.

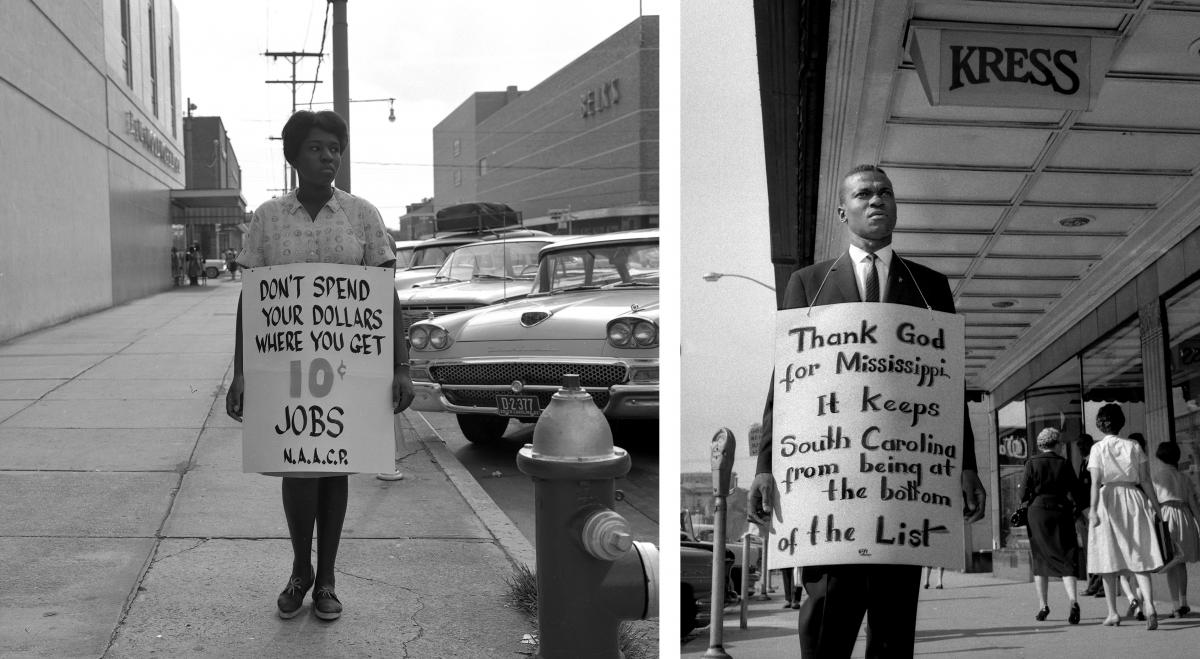

It wasn’t enough that I was green in my job. I even looked it. I was mistaken at conferences for an undergrad. Cecil didn’t care—he had been a stringer for Jet in his teens. Compared to him, I was a late bloomer. He struck me then, as now, as a man who doesn’t much care for artificial barriers.

This is another way of saying that he was—and is—a humanist.

Cecil and I didn’t dwell on the superficial elements that could have divided us. We were more than a generation apart in age, of different races, representing different fields of humanities expertise and different political affiliations, but we held the same core principles, the same commitment to democracy.

I knew that our university press was not the first one he had approached; such matters never bothered me as an editor. That book came our way in time, which was blessing enough.

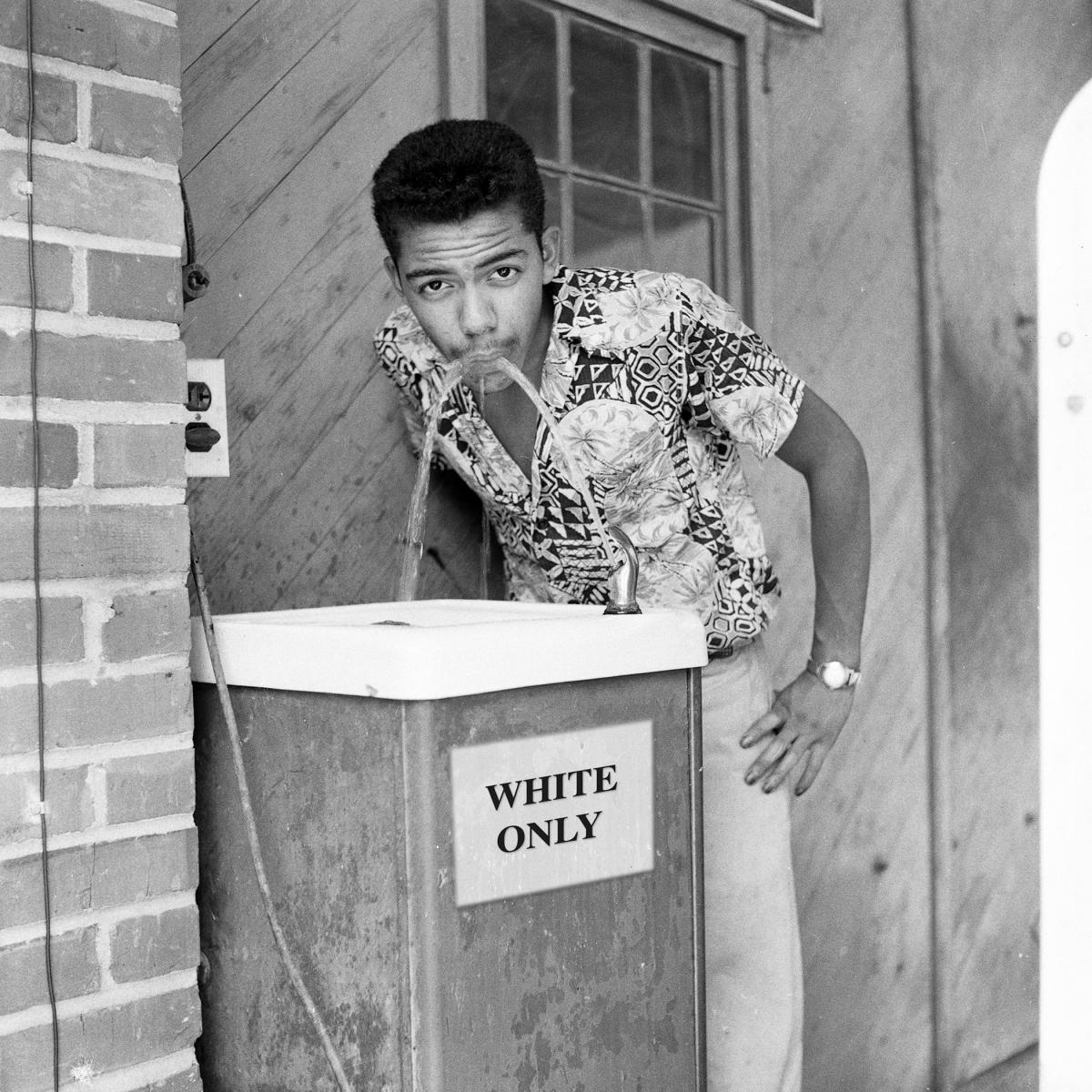

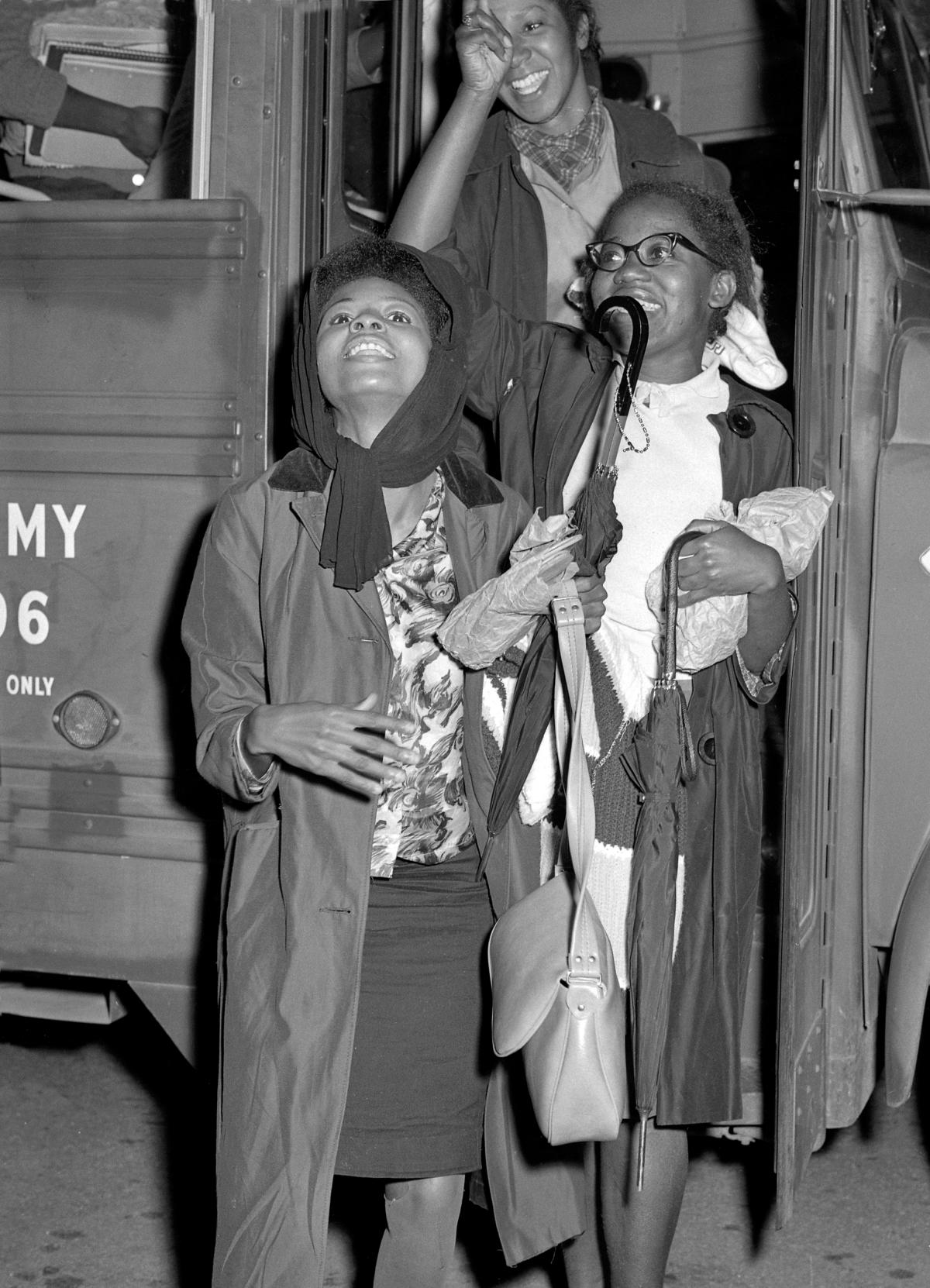

We included 200 large-format, black-and-white photographs in the book, turning away thousands more. Documenting the Orangeburg Massacre—the killing of three students and wounding of 27 on the campus of South Carolina State College—was a particularly heavy responsibility. Though this tragedy at a historically black college happened two years before the similar Kent State Massacre, it is little known by the public and little noted in textbooks. I cannot overstate how much pressure we felt when this history was entrusted to us, and we had to decide together what made it into the book and what did not.

Every transformative scholar I know, every artist of deep merit, has to sooner or later give himself or herself over to “trust.”

Cecil trusted me to produce his book, for which I remain grateful. We spoke by phone and email and in person about how to create a sustainable narrative. We experimented with font families, page dimensions, binding cloth samples, headband colors. Tracked de-bossing and smyth-sewing costs. We worried over how to best reproduce the photographs for the printer in Michigan.

Word processing was the norm by then. But there was no way to integrate so many high-resolution scans into a computer file. And even if such a massive file could be created, there was no laser printer at our university press capable of producing camera-ready pages at the appropriate quality level. We had to create the entire book in a pre-digital manner, calculating the size and placement of photographs by hand, using proportion wheels.

Cecil developed every selected photograph from original negatives. I edited his text and captions, cut the laser-printed prose into ribbons of paper with an X-Acto knife, sprayed an aerosol glue on special, large grid paper, and put down the prose and photos and rolled over them with a heavy roller pin, doing my best to follow the margins that were marked in blue pencil. I produced the pages often at night, in an aerosol fog, because I didn’t want all of my false starts to be observed by my colleagues.

Late in the process, when Cecil and I were happy about how his book was taking shape, I showed it to my managing editor. He liked it. He also noticed that some captions used the phrase “left to right,” while others said “L to R.” Those pages had to be redone completely. New photographs printed, everything done again, because the grid paper was too tacky to release the text or prints.

I wear bifocals today because of Cecil’s book. But, frankly, I never quite wanted that project to end.

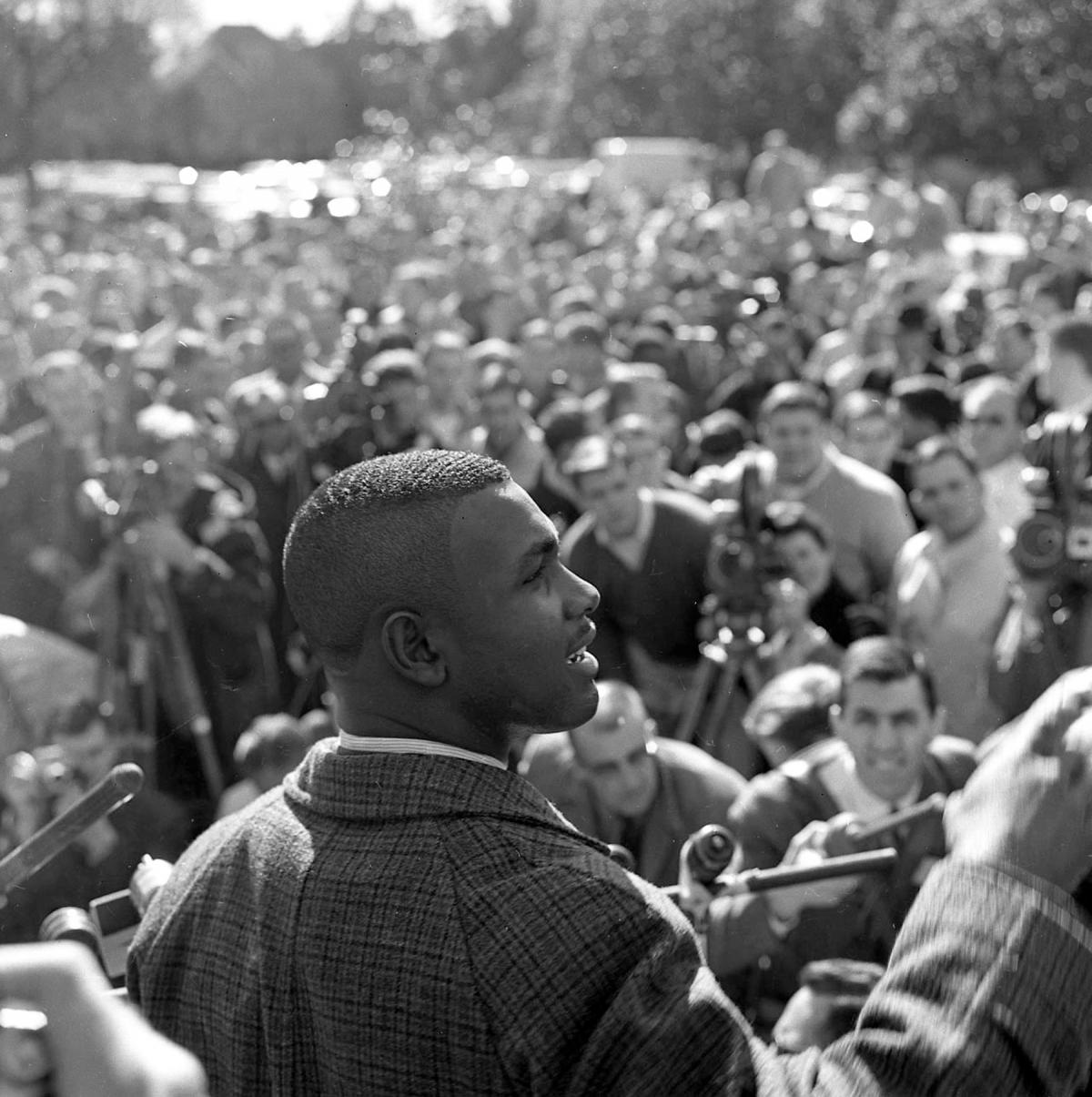

Harvey Gantt’s integration of Clemson College, John F. Kennedy’s announcement of his run for the presidency, Billy Graham’s revival crusades—Cecil had captured it all.

Cecil had a VHS tape to accompany the book, educational materials for schoolchildren, a proposal for changing the South Carolina flag while also showing the flag in historical context with others that had flown over the territory that became the state.

Cecil likes to do things on a big scale.

One of the complexities of his book sprang from that same impulse. He wanted—and ultimately got—a book that is more than a foot wide. No publisher that expects to actually make money would have agreed to that idea. So, who made the decision? In truth, the photographs did. They demanded a level of presentation. They demanded a level of attention. They demanded—they deserved—respect.

And, in his soft voice, Cecil J. Williams spoke for them.

He testified for them.

And they testified for him, and for thousands of others.

Those photographs are going to keep testifying for a long, long time into the future.

Cecil, thank you, my friend, for your courage, your goodness, your example, your service.