Celebrity interviews are such a part of today’s culture that we might be forgiven for assuming they’re a modern invention.

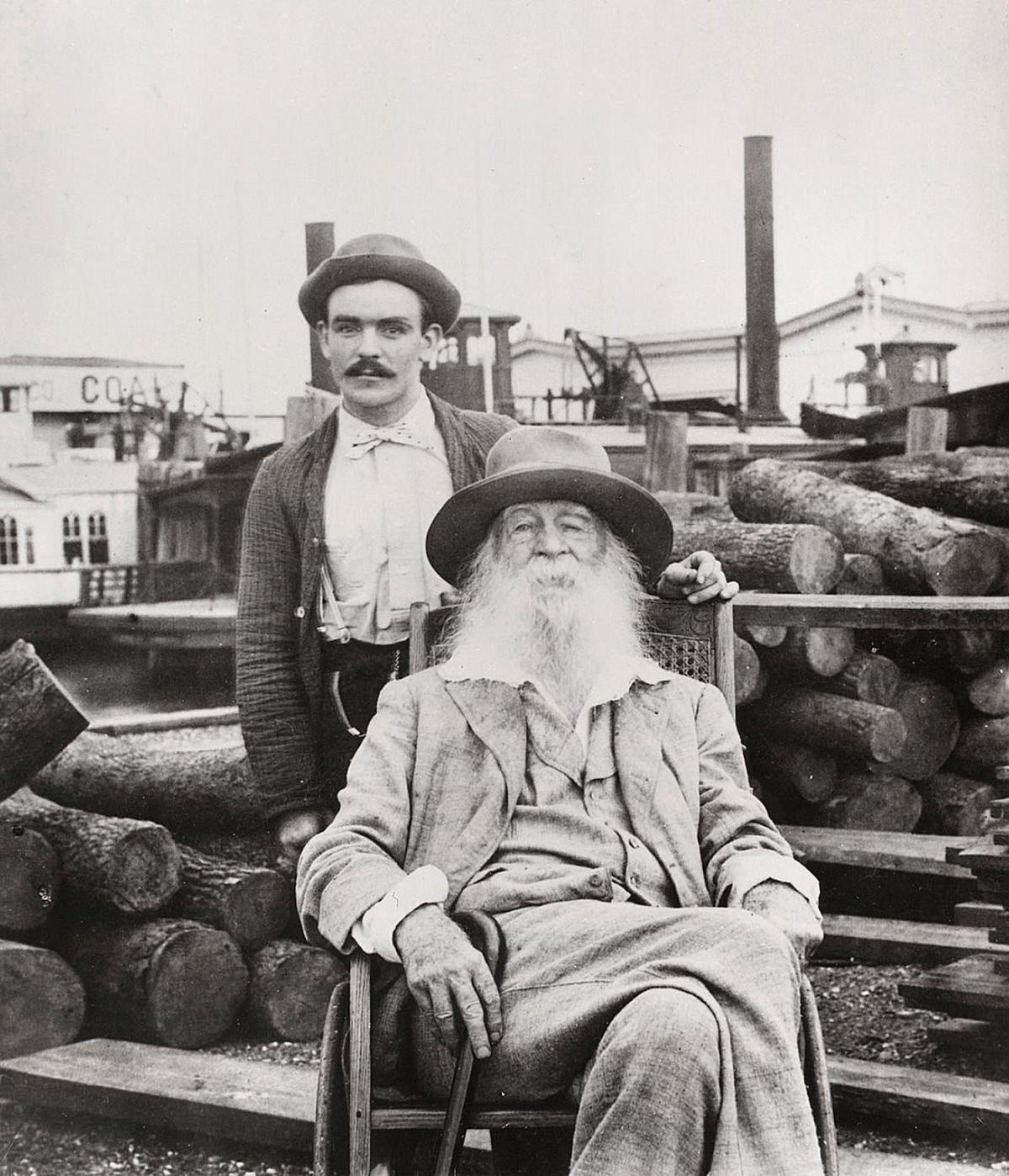

But in his final years, poet Walt Whitman (1819–1892) was visited almost every day by Horace Traubel, a bank clerk and journalist, who asked Whitman questions about his life and work and copiously recorded the answers.

Whitman’s responses eventually filled nine large volumes, encompassing a publishing project that had to be carried on by others when Traubel died before his series was completed.

Traubel (1858–1919) apparently wanted his account of Whitman’s views to be as expansive as Whitman himself, most famous for his epic poem of American life, Leaves of Grass, first published in 1855 and repeatedly revised.

If anything, the legacy of Traubel’s chronicle, titled With Walt Whitman in Camden, after Whitman’s residence in Camden, New Jersey, has been complicated by its thoroughness. It’s full of so much marginalia, including references to the Camden weather and Whitman’s housekeeping issues, that all but the most ardent Whitman fans are likely to lose interest.

But just in time for the bicentennial of Whitman’s birth—he was born on May 31, 1819—scholar Brenda Wineapple has distilled some of Traubel’s best material into Walt Whitman Speaks, a slender, 221-page volume from Library of America, a nonprofit publisher of classic American literature.

Whitman was old and in poor health when Traubel began the interviews. The poet clearly saw them as a way to communicate from beyond the grave. “I want you to speak for me when I am dead,” he told Traubel, adding that “you will be called on many a time in the future to bear witness—to quote these days, our work together, the talks, anxieties—the victories, defeats.”

Like many a later celebrity, Whitman seemed to see the interviews as a form of performance. He often speaks in certitudes, as if crafting aphorisms for a literary salon. “I take it,” he says, “there are qualities—latent forces—in all men which need to be shaken up into life: to shake them up—that is the function of the writer.” About his native tongue, Whitman was equally provocative: “Perfect English and perfect sense don’t always go together!” He was opinionated about human nature, too: “One’s egotism carries him a great way towards endurance. It is so with me—I have stuck and stuck—through a something within me which my enemies would think hopeless conceit.”

“I believe now more than ever,” Wineapple tells readers in an introduction to Walt Whitman Speaks, “that Walt Whitman remains an original, a man far ahead of his time who insisted on being himself.”

Wineapple groups her selections of Whitman’s observations into chapter topics like “Writing,” “Art and Artists,” “Love” and “Friendship.” In Wineapple’s distillation of Traubel’s magnum opus, Whitman is sometimes serene, often iconoclastic, but seldom dull.

Whitman recalls that Ralph Waldo “Emerson’s face always seemed to me so clean—as if God had just washed it off. When you looked at Emerson it never occurred to you that there could be any villainies in the world.” Whitman dismisses as overblown the “cult worship” of Shakespeare. “I do not think,” he sniffs, “Shakespeare was the all in all of literature.”

Assessing Henry David Thoreau’s legacy, Whitman says one thing “keeps him very near to me: I refer to his lawlessness—his dissent—his going his own absolute road let hell blaze all it chooses.”

About his own work, Whitman mentions his desire to create a book “for the pocket. That would tend to induce people to take me along with them and read me in the open air: I am nearly always successful with the reader in the open air.”

Walt Whitman Speaks seems like a fulfillment of Whitman’s desire—a small, portable volume, easily taken outdoors, where Whitman is still good company two centuries after his birth.