Walking along Elliot Street in Brattleboro, Vermont, on a sunny August afternoon, the air was full of voices from the past as I sauntered by the modern headquarters of the local fire department. The streets echoed with the sounds of daily commerce but listening to an audio story about the history of the site—one of many stops on the Brattleboro Words Trail—I was back with Dr. Robert Wesselhoeft, a German émigré who founded the Brattleboro Hydrotherapy Establishment in 1845. The doctor’s regimen of bathing, intense exercise, ingestion of copious amounts of water, rest, and simple food was known as the Wesselhoeft Water-Cure and attracted writers like Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to the town for a dose of the soggy treatment.

Turning onto Main Street, it was the words of Frederick Douglass, who spoke at the old town hall on January 4, 1866, that followed me. Douglass intended to give a speech about voting rights in town, but he pivoted to speak about the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln instead.

In West Brattleboro, I wandered the landscape that inspired the iconic horror writer H. P. Lovecraft and his eerie 1931 story “The Whisperer in the Darkness,” checking over my shoulder as I listened to accounts by local middle school students of Lovecraft’s source material—tales of nonhuman remains washing down into the valleys after the historic Vermont flood of 1927.

And as I drove the winding hills and valleys south of town, my companion was the voice of artist and writer Shanta Lee reading the poem “Bars Fight” by Lucy Terry Prince, one of the earliest known African-American poets and a formerly enslaved woman who created a rich and multifaceted life for herself and her family in early Vermont. Along with her husband, Abijah, Prince farmed, fought to defend her land from racist neighbors, and created a community in Guilford, Vermont, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Lee’s reading and additional historical context by author Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina added layers of meaning to the physical places where the Princes’ lives unfolded in moments both extraordinary and mundane.

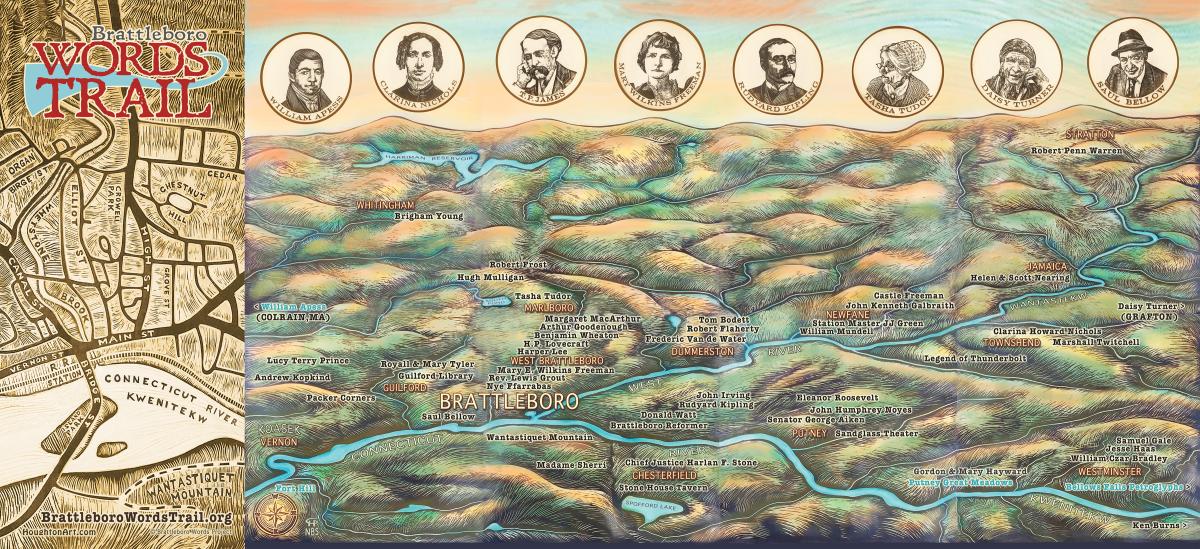

The Brattleboro Words Project, funded by a 2017 NEH Creating Humanities Communities matching grant, celebrates the unique literary and historical legacy of Brattleboro and the surrounding region. The area is known for its lively book scene, with a thriving literary festival and library, multiple independent new and used bookstores, institutions of higher education, and many full-time and part-time resident writers. It’s known, too, for its associations with literary luminaries like Rudyard Kipling, Robert Frost, and Saul Bellow, and titans of the American printing industry.

In addition to the Brattleboro Words Trail app, residents and local organizations have produced a book titled Print Town: Brattleboro’s Legacy of Words, ceramic map murals created by artist Cynthia Parker-Houghton, and a dizzying variety of public events. Performances, lectures, and workshops celebrate the expansive cast of characters who, through their words and writing, have made this corner of Vermont a home for story in all its forms.

The stories reach back to the original inhabitants of Vermont through the trail’s inclusion of Abenaki Sokoki petroglyphs carved in stone along the confluence of the Wantastekw (West River) and the Kwenitekw (Connecticut River). Submerged since the construction of a nearby dam in 1909, the carvings, along with another petroglyph site farther north, represent thousands of years of Abenaki presence in the region.

From the beginning, the organizers envisioned something more than a tourist attraction. They wanted to use a place-based approach to invite both visitors and locals to engage more deeply with the region’s history, one connected to specific locations and the people who lived in them, and to enlist community members of all ages in the creation of the trail.

William Edelglass, the project’s principal scholar, was teaching at nearby Marlboro College when he learned about the NEH grant from his Words Trail cofounder Lissa Weinmann, a writer and producer. Weinmann, who is also a partner in a community arts center located across the street from the former site of the Brattleboro Hydrotherapy Establishment, serves as the producer of the Words Trail and director of the Words Project. Edelglass, whose research explores the power of place in shaping lived experience, was immediately interested in the concept. “Focusing on place was a way to bring people together,” he said.

The idea of building a community around stories was what excited Weinmann. She described the power of learning about history while standing on the piece of earth where it happened. “It roots you when you know what happened before,” she said. “It forms a connection with other human beings.”

A team of researchers, scholars, and project leaders from the Brattleboro Literary Festival, Marlboro College, Write Action, the Brattleboro Historical Society, and the Brooks Memorial Library applied for and were awarded the NEH grant. A fundraising effort began, and, with the help of hundreds of volunteers, the Words Trail was launched in 2020.

By teaching community members to research and record the audio stories for the app, the project became more than the sum of its parts. Volunteers, including students from local schools, completed research, wrote scripts, recorded stories, and edited their pieces. Community members who thought they knew the history of the places they frequented learned how much more there was to find. Some of the associations, like Kipling’s many connections in Brattleboro and Dummerston through his wife’s family, were already well known. But others were plucked from obscurity or brought back to life after being lost to time.

Write Action member and writer Rolf Parker-Houghton, who served as principal historian on the project and helped produce Print Town, said that he loves the serendipitous nature of the project. Researching and writing about history, he said, is an “avenue for finding joy in place.”

That joy extended to the creation of the maps that illustrate the trail. Cynthia Parker-Houghton described the process of becoming absorbed in the landscape and its many people when she created the sgraffito ceramic murals as a companion piece to the trail. Making the map, she said, became “a way for people to access these stories.” Large-scale versions of the murals will be installed in Brattleboro’s Amtrak station in 2023.

Traveling from storied spot to storied spot, I found that I began to be more aware of and curious about the spaces in between. Lee, who works as a public intellectual, including as a Vermont and New Hampshire Humanities Council speaker, agreed. “Something about the project makes us look closer at the gaps,” she said. Focusing on a place “opens up opportunities to deal with the bruises” of painful, unjust, and traumatic events in history. “It forces us to grapple with the past. History becomes living and breathing.”

For Weinmann, using a physical location as a jumping-off point roots the work of historical inquiry. “Time is changing,” she said. “Place is solid.”

While the places it recognizes are solid, the trail will grow and change. Weinmann said that the project leaders have already gotten tips about more wordsmiths connected to the Brattleboro region and that more places will be added to the route. Additional audio will be added to existing stops as part of the concept of “deep mapping,” or looking at counternarratives and multiple perspectives of a site over time. “It was a sacred responsibility to us to reflect the community back to itself,” Weinmann said.

At the Brattleboro Retreat Farm north of town, the app has Rich Holschuh, an Indigenous cultural advocate and member of the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs, and other experts contextualizing a Daughters of the American Revolution monument with information about the existing Abenaki presence and history of the site before colonization.

“The meaning of a place is always contested,” Edelglass said. “One person’s gorgeous, beautiful place is the site of another person’s loss or exclusion.”

Many of the stops on the trail center on long-dead authors, but contemporary Vermont writers are included, too, and their stories add a layer of reflection about the experience of trying to make a living as a working writer in Vermont, with all the challenges and meaning it brings. Brattleboro’s municipal building is paired with the words of local crime writer Archer Mayor. Tom Bodett, a writer and broadcast personality who lives in Dummerston, was recorded talking about coming to understand his vocation as that of a storyteller. “It adds meaning to a life when you have to describe it,” he said. “Our brains force everything into a narrative.”

Sandy Rouse of the Brattleboro Literary Festival, and one of the project leaders, said that the town’s setting is central to the work of celebrating contemporary writers. “The festival has always been place-based,” she said, bringing writers and their stories out into the community for events at meaningful locations.

I finished up my day on the Words Trail by leaving Vermont for Massachusetts. I turned around and drove back to stop at the Vermont Welcome Center on Interstate 91 in Guilford, where a recently installed state historical marker honors the legacy of Abijah and Lucy Terry Prince. Reading the words on the plaque detailing the extraordinary lives of these early New Englanders, I heard Lee’s voice reading Prince’s words once again. They traveled through time and space to reach me in the town where she has taken her place in a far-reaching and growing community of wordsmiths.