In this excerpt from Sister Novelists, Devoney Looser tells the story of Jane and Anna Maria Porter, whose novels of love and war earned them a devoted following in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries in Britain and around the world.

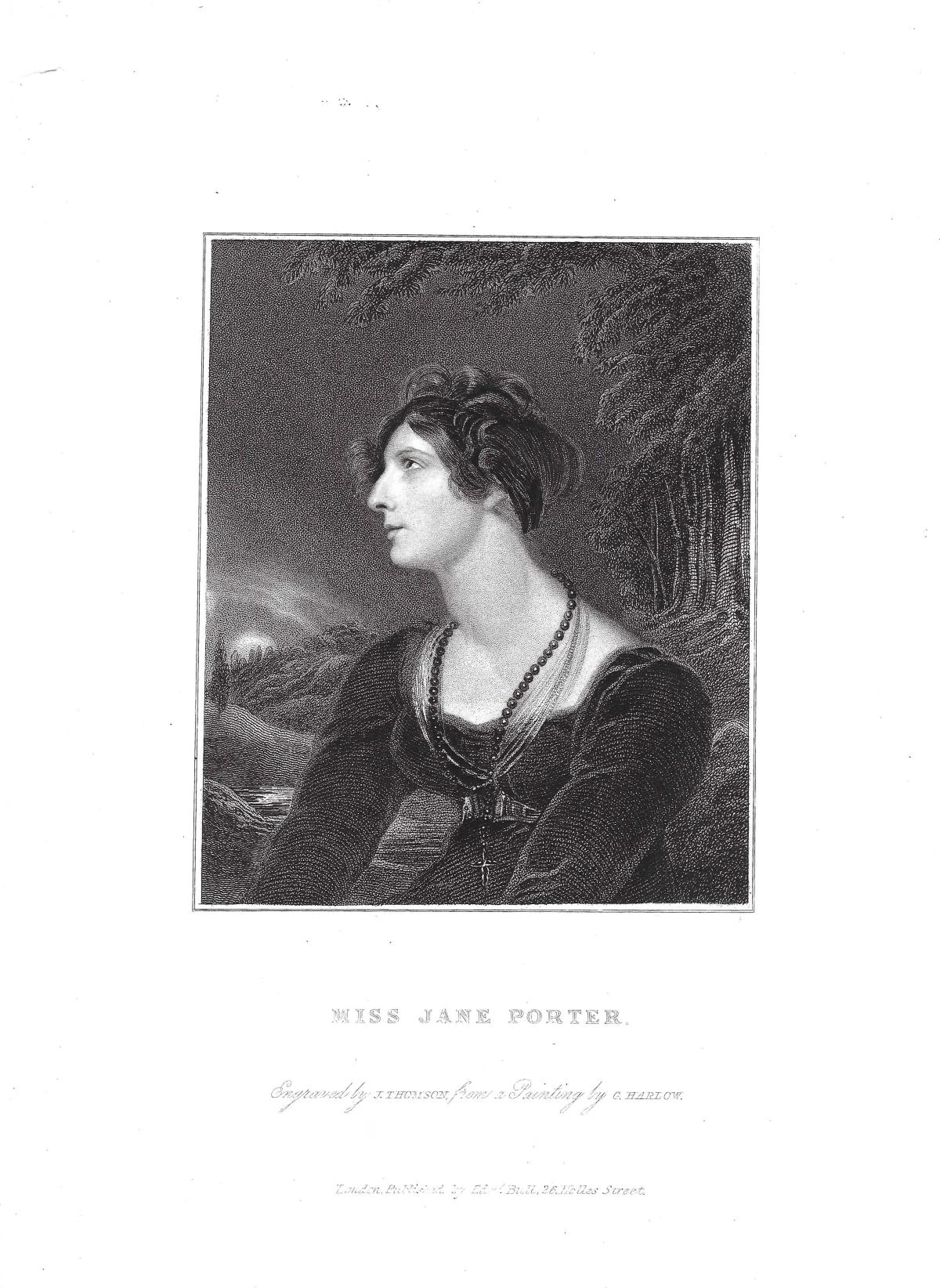

Miss Jane Porter and Miss Anna Maria Porter were the most famous sister novelists before the Brontës. People went to great lengths to see these female curiosities, who were hailed as literary wonders in Regency London. The sisters were known to be beauties; they’d sat as models for famous painters. They traveled in the same circles as celebrity actors, poets, activists, publishers, and politicians. They hobnobbed with nobles and royalty. A marquess, it was said, once paid to get a glimpse of them.

But not everyone approved. At the beginning of their careers, anonymous reviewers repeatedly told the ambitious sisters they should give up on novel-writing—and on having ambitions. Yet most readers ended up in awe of their literary powers. Their dozens of heartrending, uplifting novels of love and war were seen as so true to life that it seemed impossible the sisters hadn’t been on battlefields themselves.

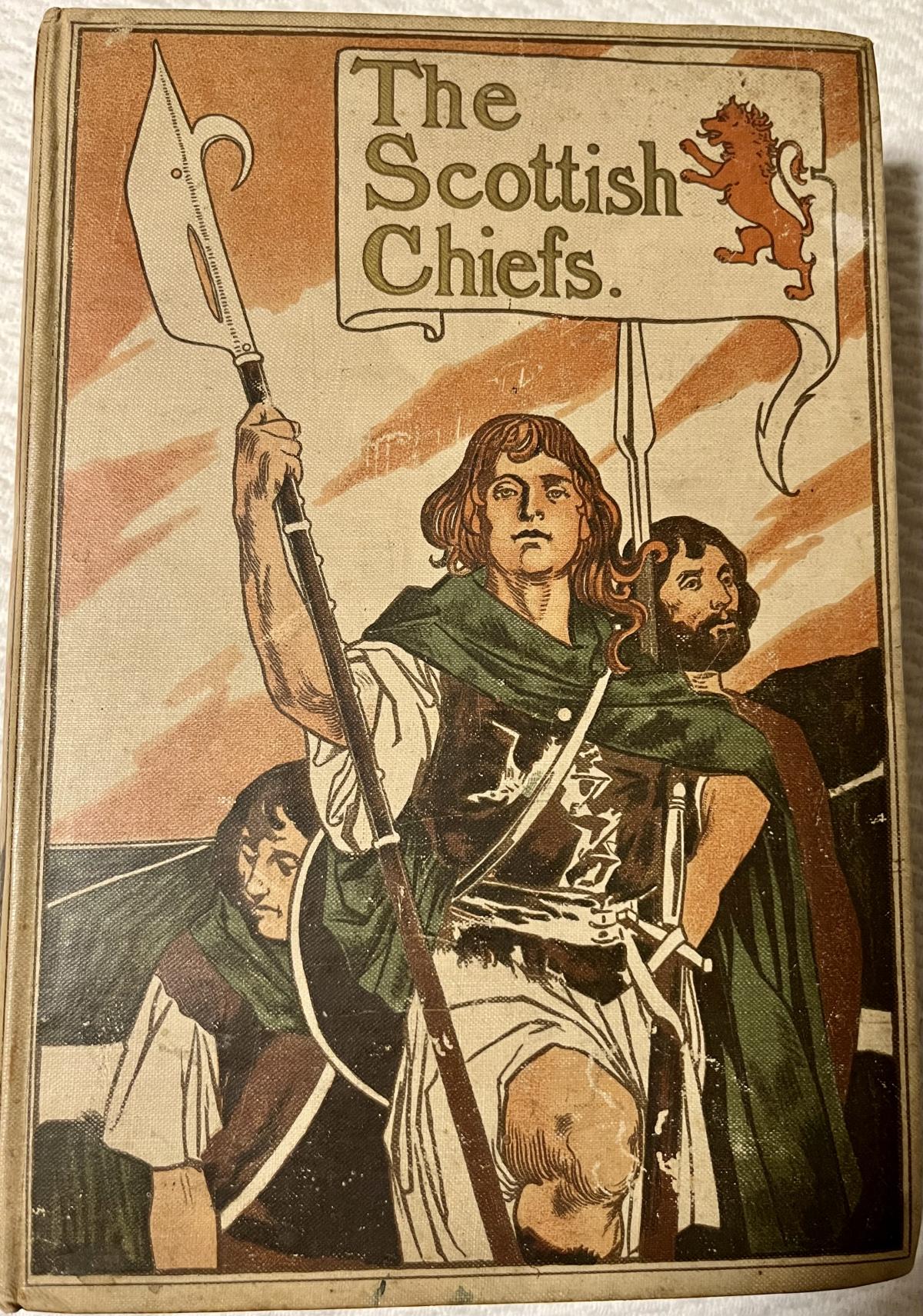

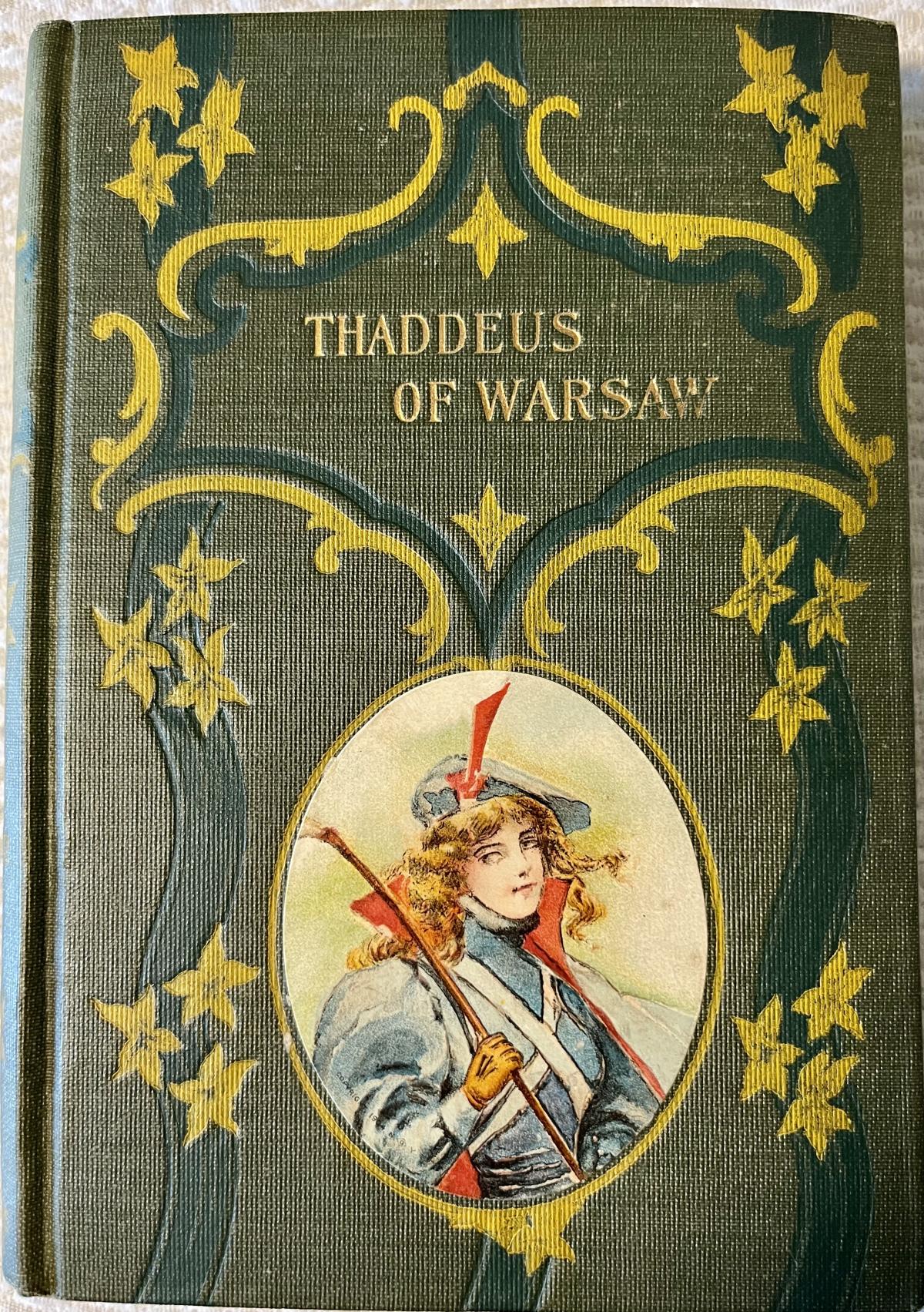

The Misses Porter gained global fame, with Jane the more famous and Maria (as she was called) the more prolific sister. Jane’s best-selling historical novel The Scottish Chiefs (1810) was said to be Queen Victoria’s favorite book. Across the Atlantic, it was President Andrew Jackson’s favorite. Novelist William Thackeray, author of Vanity Fair, remembered The Scottish Chiefs as the first novel he’d read as a boy. He’d so cherished it that he couldn’t “read to the end . . . of that dear delightful book for crying,” because finishing it would have been “as sad as going back to school.” Jane’s earlier novel of war-torn Poland, Thaddeus of Warsaw (1803), was also a literary phenomenon. Emily Dickinson’s well-worn copies of Jane’s two best-selling novels have dozens of folded-over page corners, showing intense engagement with the books. Fans told Jane they stayed up all night reading Thaddeus of Warsaw, losing themselves in its pages. Her signature books about history’s underdog war heroes in nations fighting off tyrants were considered politically dangerous enough to be banned by Napoleon.

Until the end of her life, Jane’s novels were widely read, rarely out of print, and translated into many languages. After she died, her works lived on, although they were shortened, and then relegated to children’s literature. The Scottish Chiefs was abridged with illustrations by N. C. Wyeth in the 1920s. In the 1950s, it was featured as a Classics Illustrated comic book. Later still, Jane’s novel served as the probable, though uncredited, source text for Mel Gibson’s Academy Award–winning film Braveheart (1995). But by then, the name Jane Porter was best known as Tarzan’s wife, and the original Jane Porter’s less celebrated sister, Anna Maria Porter, was no more than a footnote.

None of this was predictable, neither the rapid rise to fame nor the gradual forgetting. The Porter girls came up in the world from what the late eighteenth-century elite would have called nothing. Such girls, born portionless, had few prospects. Then the sisters became fatherless. Without male relatives to depend on, downwardly mobile single girls might hope to become seamstresses or, with some education, governesses. If attractive and good with numbers, they might marry tradesmen. The world might have expected the Porter sisters to become wives to struggling medical men like their late father.

But the Porters, who loved reading books from an early age, broke the mold. From a very early age, the sisters began to amuse each other with the products of their pens. They wrote long, loving letters, full of silly jokes and make-believe intrigue. They chose outlandish pseudonyms and scrawled playful postscripts to each other at the end of dutiful letters to their uneducated, widowed mother. In her early teens, Maria teased Jane about her melodramatic prose and bad handwriting, declaring that her sister’s topsy-turvy commas looked drunk.

Soon the sisters were exchanging letters in rhyming verse. In one poem-letter, Maria closed with, “I’ll sheath my pen, then stir my fire / and sign myself your fond Maria-r.” It’s how we know she pronounced her name with a low back vowel. Maria grasped early on that the life of the mind and pen could serve as a pleasure-filled battle of rapier wit, even for struggling girls confined to the domestic routines of stoking household fires. For Maria and Jane, their pens were their swords. The Porter family’s shabby series of rented hearths and homes were places that lit up their imaginations. When Mrs. Porter, their plainspoken mother, declared their London lodgings looked like a dog hole, Jane disagreed. She said it was the manner of a place that determined its elegance, not its size. The sisters imagined greater things, then almost wrote them into being.

Jane and Maria, armed with no more than a few years of charity school education, had little help in learning how to write. They became each other’s first audience. Together they built word-worlds, took oaths of sincerity, and expressed mutual admiration. One of the sisters’ favorite words was “blazing.” In their letters, passions blazed. Gossip blazed. Beaux blazed. Each sister told the other that her fiction blazed with genius.

They decided, against all prevailing advice, to seek print. In 1790, Jane, at age fourteen, wrote a poem about a young female author who stayed up late, writing by candlelight. The author dreamily records her visions of mythical gods, muses, and cupids. She writes about Venus’s eyes shooting forth a fatal blaze that inspires creativity in the girl-author. But in the middle of this reverie of night-writing, the poem’s speaker is interrupted by a knock on her door. Her male friend has come to report disappointing news. His efforts to sell her writings have been in vain. The booksellers have risen up against the girl’s attempt to publish. Nevertheless, she’s undeterred.

“One cries I’m fool or rather mad,” she complains of the booksellers. “Others my works are cursed bad. / I start and vow it can’t be true, / And then sit down to write to you.”

That trusted “you” for Jane—the one who kept her writing, despite the criticisms of the male-dominated publishing world—was Maria. The young sisters soon turned from writing childish letters and light verse to serious poems, short stories, essays, histories, novels, pamphlets, and plays. They wrote of the horrors of war, the beauties of the natural world, moral philosophy, classical history, friendship, and families. They found friendly editors in newspapers and magazines. The once-skeptical book publishers were eventually won over.

Jane and Maria grew up similarly as authors but became distinctly different women in looks and personality. Maria—the more impulsive, younger sister—was a social being, lively and loquacious. Those who knew her best worried that she fell in love too readily, not only with attractive men but with friends, children, dogs, cats, birds, and breezes. She was thought pretty, with a round, girlish, pleasing face, azure eyes, and blonde hair, producing bright, sunshiny good looks. She could draw people in with her gentle, joyful enthusiasm.

Jane was called the more beautiful sister—tall, with long, auburn hair and striking features. She projected a graceful, calm placidity. Later in life, she could command rooms upon entering them, with her conspicuous good looks and quiet authority. It took her some years to leverage that power, due to an early, awkward shyness that masked her great inner strength. From a young age, Jane was a sought-after adviser. Her own mother relied entirely on her eldest daughter’s sound judgment.

Jane and Maria’s opposite personalities could have inspired Jane Austen’s sister-heroines, Elinor and Marianne Dashwood, of Sense and Sensibility (1811), although there’s no proof of connection. In situations where Maria rushed in, Jane carefully considered. From their youth, the Porter sisters were likened to two contrasting poems by venerated seventeenth-century author John Milton. His “Il Penseroso” describes the serious man in deep thought—learned, melancholy, and pensive—while “L’Allegro” investigates the happy man of mirth and play. Jane’s nickname was “Il Penseroso,” and Maria’s was “L’Allegro.”

It was understandable that the sisters would find nicknames in the male-authored literary canon. Both revered history’s great men. In their books, they advocated for what then seemed a pressing need in Britain—inspiring rudderless young men of talent to become upstanding sons, brothers, husbands, and military heroes who might lead nations and slay villains, particularly during the Napoleonic Wars. Yet, as much as they revered heroes, the sisters recognized how cruelly limited their own options were in not having been born male.

“But my love, had you been born a Man with your head & heart what an ornament to society you would have been,” Maria wrote to her sister. “I love you more than ever, Jane!”

The sisters worshipped history’s great women, too—although there would have seemed fewer of them. They also sought out living examples of female greatness. In their teens, they formed friendships with famous and infamous women of genius. By their late twenties, the sisters were known as female geniuses themselves. Jane and Maria’s brilliant literary careers helped transform the “authoress” into a more respectable, formidable type. The obstacles they faced in doing so were unintentionally captured in a single sentence from a male literary acquaintance. He wrote, “I liked these two sisters exceedingly, although they were authoresses.”

Female authorship in the early nineteenth century was fraught. Educated women weren’t supposed to do anything for pay because it was said to tarnish femininity and jeopardize fragile middle-class standing. Elites couldn’t decide whether a scribbling woman was a wonder or a monster. Once such a woman published under her own name, the die was cast. Although fame had been something the Porter sisters prized in their youth, especially Jane, it came at a price. “I seriously and sincerely declare that nothing but necessity ought to have made me an authoress,” Maria confessed after publishing her sixth book. “I see that I was never meant for one.” She often felt she wasn’t cut out for public life.

The necessity that compelled her to authorship was financial. The Porter family’s three chronically debt-saddled brothers offered little help to their widowed mother and unmarried sisters—a dereliction of traditional masculine duty. The conventional way for the Porter sisters to secure their future—and the future comfort of their “dearer than self” mother—would have been to marry well. But neither sister took a mercenary approach to love. They refused the prevailing idea that securing a well-off husband was a necessary business transaction. At the same time, they boldly negotiated the sale of their own writings.

There’s no question that the perfect heroes Jane and Maria dreamed up in the pages of their books had an impact on the men they imagined marrying. The sisters’ ideals for male intelligence, charisma, and virtue were high, but the men they fell for proved very wide of the mark. And both sisters fell hard—often for colorful, charismatic men who were living double lives—in an era when a polite woman wasn’t supposed to discover her own feelings for a man until he’d revealed his own first. Another problem was that most educated men of the time had their own visions of a perfect wife, and she bore little resemblance to a clever, talented literary woman. It was thought unseemly for her to sully a good reputation by immodestly publishing her works.

For the Porter sisters, it was a catch-22: While single, they needed to write to support themselves. They maximized profits by publishing under their own names. But pursuing literary careers made it less likely they’d find the heroic husbands they desired. Extraordinary men were sometimes fascinated by bold, intellectual women with public reputations, yet such men were encouraged to marry subservient, delicate, and unworldly helpmates. Ideally, these self-effacing innocents were also rich.

These limiting beliefs carried over into the literary world. Female authors relied on fathers or brothers to sell their writing to publishers, most of whom were male, because it was polite and expected. Jane’s early poem describing her male friend’s unsuccessful attempts to sell her writing acknowledges that custom. But without the benefit of effective help from a father, brother, or male friend, Jane unconventionally stepped into the role of literary agent. She got the best deals she could for herself and Maria. The sisters took care of their own business, although, as Jane put it, “Men of Business are not always at the command of our sex.”

The sisters used both stereotypically masculine and feminine traits in their negotiations. They felt they had to. “Booksellers, are like Lovers,” Jane once wrote to Maria. “We must be coy-ish, if we would keep advantage.” Maria, too, understood the publishing game. “At present, money is our aim, and everything that is fair and honest must be attempted to obtain it,” she told Jane.

With this philosophy, and pressing economic need, Maria published book after book, to collect the sums each title brought. Jane faithfully recopied and lightly edited Maria’s rapidly crafted works and painstakingly composed her own. The sisters worked so hard, with their different habits of composition, that they often wrote themselves sick. Despite difficult circumstances, their talents found expression. Their achievements were immense.

Jane and Maria’s groundbreaking fiction was historically researched, morally uplifting, and brilliantly inventive. Their signature sensitive male protagonists cried at home and battled abroad. They married resilient, chaste women, after having fought off desirous femmes fatales. The stories involved deception, cross-dressing, madness, imprisonment, and murder. These novels were meant to entertain but also to lead readers into the further study of history. Most of all, their books were meant to inspire admirable behavior and good character.

The Porters’ fiction was exceptionally important in its time. Their stories are sprawling, and their characters well drawn, the result of minute social observation and extensive historical research. Yet the descriptions and coincidences might sometimes strike today’s readers as laying it on a bit thick. The good characters are unbelievably good. The moral lessons are pat. That was the expectation then for higher sorts of literature, especially from polite female pens. The sisters dutifully followed those conventions.

But the place where Jane and Maria weren’t afraid to step off the beaten path to show life as it was, was in their private letters. Because their emotionally raw and confessional correspondence wasn’t designed for other readers’ eyes, the sisters often went to great lengths to conceal its contents. They used initials and mythological names to hide the identities of suitors, rivals, and enemies. That way, if a letter were intercepted before delivery, or its pages seen by a curious brother, their communications might be concealed. The sisters sometimes used banal phrases as secret codes. They plotted the use of invisible ink. They trusted, encouraged, and advised each other, in affairs of authorship, as well as the heart.

“With sisters, who are together all day, and generally all night—they cannot look nor move without observation,” Jane once described her relationship with Maria. “Hardly a thought can pass in their minds, but must be seen to each other.”

Jane called herself the echo of her sister’s feelings and sentiments. Maria boasted that no one who ever met “my Jane” lost sight of her again willingly. When one sister made a new friend, the other longed to be introduced. “Is there any person, dear to my Mother and sister,” Maria wrote, “that can fail of becoming so to me?”

Their letters proved a training ground, not only for lifelong, sisterly love but also for practicing the craft of novel-writing. Jane and Maria recorded scenes they witnessed, and entire conversations they overheard, to capture the adventures of their daily lives. Their letters became a storehouse from which to craft fiction. When Maria wrote to Jane from Brighton about the way moonlight shined on the ocean, Jane encouraged her to save the passage, to insert in some future book. “All such contemplations are as useful to us, as they are delightful,” Jane wrote, “for they form the veins of gold from which we work our future fabricks in ‘fairy land’.”

The sisters wrote often, too, to friends and family. Jane shared with Maria her secrets of success as a correspondent. When she wrote to people, Jane said it was generally just as she talked to them—more in their own strain than in her own. Jane tried on voices and identities to please listeners and recipients.

One famous and wealthy friend, Thomas Hammersley, who served as banker to the Prince of Wales, told Jane people would want to save the letters of “such a mind like yours.” He predicted, “Every paper which comes from you will be worth preserving.” He wanted her to think of posterity and collectors as she composed them. “May I take the liberty of making a remark which will be to the advantage of your other correspondents as well as myself,” Hammersley wrote, “to leave a margin in the folding part of the paper where I have marked. Your letters may then be pinned or stitched together without any of the writing being obscured.”

Of that suggestion, Jane wrote to her sister, “I could not but smile at his hint, . . . I, who would wish to have them all burnt as soon as the receiver has read them!”

It’s fortunate they weren’t destroyed. Two distinguished literary men once declared that Jane’s private letters would put her on a par with eighteenth-century literary greats like Jonathan Swift and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. These male friends believed Miss Jane Porter would someday be ranked among the illustrious females of her country, if her letters were collected and published. So far, very few have been.

Jane was amused that her correspondence was so prized, but she came to acknowledge its value. She once wrote to Maria about their letters, “We ought to collect these histories of our own times.” By the end of their lives, the sisters had exchanged thousands of pages of observations and reports about their acquaintances and friends, including the era’s most famous novelists, poets, artists, actors, and military men, as well as several royals and many others of rank and title. Jane and her admirers fanned the flames of her celebrity into the Victorian era. At her death, she was called one of the most distinguished novelists Britain had ever produced.

The pathbreaking experiences of the Porter sisters made possible the careers of Austen, the Brontës, and George Eliot, until each of these followers outpaced the sisters in fame and reputation. Memory of their literary achievements in historical fiction, which gradually faded, deserves to be reignited. Yet posterity may decide that their greatest masterpiece is a vast, uplifting, and heartrending correspondence, filled with stories of literary intrigue, financial disasters, and secret lovers. The Porter sisters describe it all in throbbing detail, giving it to us straight—what it was like to try to live and love as brilliant, accomplished, and cash-strapped women writers, in the whirl of the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries in Britain. The lives of these remarkable sisters may sometimes read like a novel, but it’s a true, blazing history.