Before people could easily post their opinions on Twitter, they traded barbs and fiery accusations via hastily typeset and cheaply printed pamphlets, oftentimes inciting fear and fueling outrage. As with some media today, there were no rules imposing fact verification or source attribution, leading to the spread of what we might label “fake news.” Back when printing presses ruled the day, such eruptions were called “pamphlet wars.”

Tracing their antecedents to sixteenth-century Europe, pamphlet wars raged with equal intensity in America. One example originated in Boston and swept through Great Britain in 1764, just as Parliament was meeting to discuss the Stamp Act, launching a pamphlet war in the United Kingdom over the fate of the colonies, political and economic reform, and more. Another all-consuming pamphlet war would take hold on American soil, this one ignited by the massacre of twenty Conestoga Indians by Pennsylvania frontiersmen. Despite its considerable paper trail, it has largely remained on the margins of American history.

The Pamphlet War of 1764, as the exchange became known, began as an unintended consequence of the French and Indian War, which ended with France ceding its North American strongholds to Great Britain and Spain. Tribes that had sided with the French, such as the Huron, Seneca, and Miami, were forced out of their ancestral homes, paving the way for British colonization. In response, these displaced Indians raided settler townships along the Ohio and Susquehanna valleys, leaving hundreds of colonists dead while sowing seeds of fear and mistrust throughout the frontier.

There should have been little unease in the Paxtang community in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, where Conestoga tribespeople had lived near colonists for years. At the Shackamaxon Treaty of 1682, Governor William Penn supposedly called for peace and goodwill between the Quakers and their new neighbors—though no official record exists, several ancillary materials including wampum belts among the Penn family possessions indicate an exchange that helped maintain the peace. That changed when rumors spread that members of the tribe were planning attacks and providing intelligence to other warring factions—both untrue. When the Pennsylvania Assembly refused repeated requests to send an armed detachment to Paxtang for protection, a group of settlers calling themselves the “Paxton Boys” formed a militia with the stated goal of defending Pennsylvania’s western frontier. After mounting a failed attack on a community of Delaware Indians, they trained their anger on the Conestoga. What happened next was reported by Benjamin Franklin in A Narrative of the Late Massacres, in Lancaster County, of a Number of Indians, Friends of this Province, By Persons Unknown, a pamphlet printed in Philadelphia early in 1764:

On Wednesday, the 14th of December, 1763, Fifty-seven Men, from some of our Frontier Townships . . . came, all well-mounted, and armed with Firelocks, Hangers and Hatchets, having travelled through the Country in the Night, to Conestogoe Manor. There they surrounded the Small Village of Indian Huts, and just at Break of Day broke into them all at once. Only three Men, two Women, and a young Boy, were found at home, the rest being out among the neighbouring White People. . . . These poor defencseless Creatures were immediately fired upon, stabbed and hatcheted to Death! . . . All of them were scalped, and otherwise horribly mangled. Then their Huts were set on Fire.

Fourteen remaining Conestoga were moved to the nearby Lancaster jail by local magistrates to keep them safe from further attack, but on December 27, the Paxton Boys arrived and butchered the group of mostly women and children. Franklin recounted the second round of massacres in Narrative with equal horror:

Fifty of them, armed as before, dismounting, went directly to the Work-house, and by Violence broke open the Door, and entered with the utmost Fury in their Countenances. When the poor Wretches saw they had no Protection nigh, nor could possibly escape, and being without the least Weapon for Defence, they divided into their little Families, the Children clinging to the Parents; they fell on their Knees, protested their Innocence, declared their Love to the English, and that, in their whole Lives, they had never done them Injury; and in this Posture they all received the Hatchet! Men, Women and little Children—were every one inhumanly murdered!—in cold Blood!

Next, the Paxton Boys set out for Philadelphia as their ranks swelled to two hundred fifty men. On February 7, the caravan was met on the outskirts of the city by a delegation sent by the governor and council that included Franklin. The Paxton Boys agreed to end their rampage and vent their frustration in print. The ink-drenched battle that followed pitted neighbor against neighbor, and would account for nearly a fifth of all publications printed in Pennsylvania in 1764.

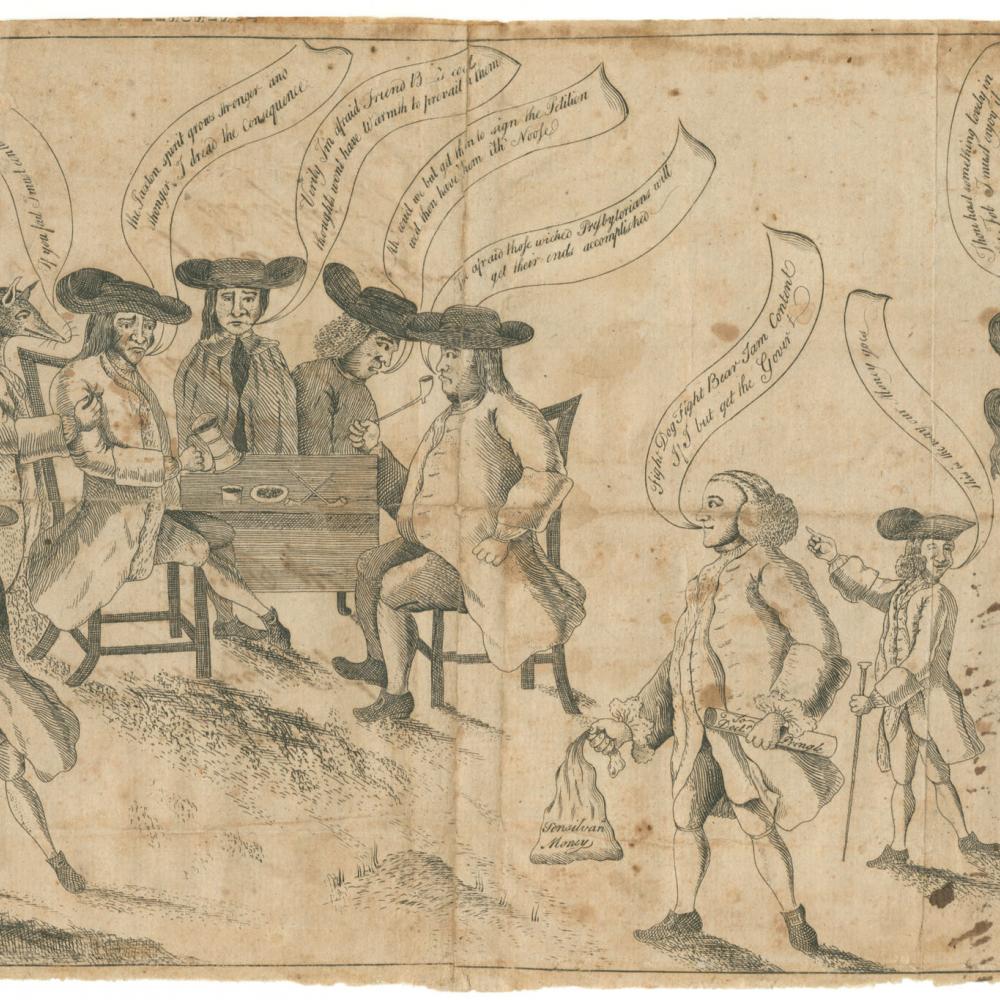

At issue were fundamental questions of personal freedom and adherence to the law of the land, along with angry concerns as to whether the government had done enough to protect its citizens. There were other massacres of native people at this time, some even bloodier and more egregious, though few generated more debate and recrimination, with charges of treason and hypocrisy flowing back and forth. Political cartoons depicted Quakers and Indians riding colonists like horses, suggesting Philadelphia’s elites, including Benjamin Franklin, cared little for their frontier brethren. Pro-Paxtons, meanwhile, were caricatured as country bumpkins and said to be no better than those they had butchered. In short, each side painted the other as fakes and frauds.

Much of Franklin’s writing on the topic can be found in the Franklin Collection at Yale University, considered the most extensive archive of material by and about this Founding Father. Since 1976, NEH has funded the editing and publication of that massive effort, which is estimated to reach 47 volumes upon completion. Those documents have slowly been digitized and many are now accessible via an online database.

Franklin was a prolific pamphleteer, with examples dating from 1729, when he turned to the format to argue for paper currency in the colonies. He employed the medium again in 1764 on the heels of the Conestoga massacres. His emotions and political leanings on full display as he attempted to win over his Christian audience, Franklin opened Narrative by naming the dead, underscoring their English names: “Peggy was Shehaes’s Daughter. . . . John was another good old Man; his Son Harry helped to support him. . . .” Having reeled in his reader, Franklin employed all his skills of persuasion to portray the massacres as nothing less than a bloody, unprovoked attack and a public repudiation of the rule of law.

Meanwhile, the pro-Paxton delegation printed pamphlets, sharing their side of the story, proving completely adept with the format. The earliest pro-Paxton material came from Matthew Smith and James Gibson, the de facto leaders of the Paxtang frontiersmen. No less than a week after meeting Franklin and the Quaker delegation, Smith and Gibson had already completed Declaration and Remonstrance of the distressed and bleeding Frontier inhabitants of the Province of Pennsylvania, which quickly became one of the more influential pro-Paxton pamphlets.

Interestingly, the first part, A Declaration, had been composed prior to the meeting—an indication, perhaps, that the pro-Paxton delegation was already well aware that they would need to prove their case to the public. It was later combined with the second part, Remonstrance, and published as one. Together, the pair of writings laid out the justification for murder as an eradication of enemies of the Crown:

THESE Indians known to be firmly connected in Friendship with our openly avowed imbittered Enemies; and some of whom have, by several Oaths, been proved to be Murderers; and, who, by their better Acquaintance with the Situation and State of our Frontiers, were more capable of doing us Mischief, we saw with Indignation cherished and caressed as dearest Friends— But this alas! is but a Part, a small Part of that excessive Regard manifested to Indians beyond his Majesty’s loyal Subjects, whereof we complain: And which together with various other Grievances have not only enflamed with Resentment the Breasts of a Number, and urged them to the disagreable Evidence of it, they have been constrained to give, but have heavily displeased, by far, the greatest part of the good Inhabitants of this Province.

In this fiery testimony, the Paxton Boys are faithful British subjects and their actions merely the unintended consequences of the Assembly neglecting its duty to defend the people of Paxtang against “his Majesty’s worst of Enemies.” This salvo served as a rallying cry for victims of Indian raids who believed, as Franklin sarcastically wrote in Narrative of the Late Massacres that, “if an Indian injures me, does it follow that I may revenge that Injury on all Indians?”

In his NEH-supported book, Revolutionary Networks: The Business and Politics of Printing the News 1763–1789, Framingham State University associate professor Joseph Adelman explores how printers helped facilitate political discourse and ideology during the American Revolution, and the Pamphlet War of 1764 was one example of printers shaping public opinion: “[Pamphlets] could be published quickly and sold relatively cheaply. That speed meant that pamphlets could serve as a medium of rapid response that allowed for greater elaboration than the newspaper.” Not incidentally, the “business of protest” proved lucrative for colonial printers who often teetered on the edge of financial stability. “Pamphlets in the colonial revolutionary era often tend to spring from these local disputes,” Adelman explained. “Newspapers carried local discussion and local conversation, but were geared towards local advertising and news from elsewhere. Pamphlets came out in the local community the day that they were ready, and had an impact locally.” And printers were only too willing to oblige paying customers with an opinion to share.

The Pamphlet War became so intense that Philadelphia pushed ahead of Boston in published pieces for the year. Eventually, the pro-Paxton faction prevailed, and in a record election turnout booted out of office most Quaker Assembly members, among them Benjamin Franklin, who had become the top target for Pro-Paxton pamphleteers. And although Governor John Penn called for the Paxton Boys to be tried for their crimes, none ever were.

“This small group of vigilantes upended the peaceful settlement at Conestoga Indiantown, and set a violent precedent for westward conquest,” Will Fenton of the Library Company of Philadelphia told me. He is the creator of Digital Paxton, a recently completed, online, open-access archive of printed materials and manuscripts generated during the Pamphlet War of 1764. It wasn’t just Pennsylvania’s first pamphlet war, Fenton says, but a turning point in colonialism and westward conquest. “Supporters of the Paxton Boys and their critics chose the press as their weapon of choice, battling in print in a way not so different from the Twitter wars of today.” Additionally, he explained, “the Pamphlet War marked a new development in early American print culture, where satire, political propaganda, and fake news shaped debate and opinion.”

Currently, Digital Paxton comprises 69 pamphlets, three books, nine political cartoons, sixteen art works, sixteen broadsides, 26 newspaper and periodical issues, 128 manuscript records, and 3,000 print-quality images, all free to examine on the spot or to download. Twenty research libraries and cultural institutions, including the American Antiquarian Society, the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, the Library of Congress, and the National Archives have contributed material to the online repository.

“Digital Paxton is by no means comprehensive, but I hope that students and researchers treat this database as an invitation to further inquiry,” Fenton said. “In fact, I hope it is used as an entry point to explore, for example, Haverford College’s Quaker and Special Collections or to become a reader at the American Philosophical Society.”

Notably missing in these historical documents, however, is the Conestoga perspective. To retell the story of the murders, the library published a graphic novel—which is rather fitting since much of propaganda from 1764 appeared as engravings and political cartoons. “The graphic novel is the ideal vehicle for social justice,” said Fenton. Since Art Spiegelman examined the Holocaust in his award-winning Maus series, graphic novelists have embraced this form to speak directly to young people about difficult topics.

Author Lee Francis and illustrator Weshoyot Alvitre were tapped to breathe life into this book, entitled Ghost River:The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga and published in the fall of 2019. Francis, a member of the Laguna Pueblo from Albuquerque, New Mexico, founded Red Planet Books & Comics. His first graphic novel dealt with the Native American code-talkers from World War I to the Korean War. “I focus on stories by peeling away the pop culture narrative that has dominated our native understanding,” Francis said.

Francis and Alvitre trekked to present-day Lancaster County with Fenton to see where the massacres occurred. En route, Francis noticed a farmhouse flying a large Confederate flag. “The spirit of the frontier in rural Pennsylvania was still very much alive,” recalled Francis. “But to do this right, we had a responsibility to go into the community and talk to the Conestoga and Susquehannock. Although the Conestoga did not write down their experiences, this legacy was passed down orally.”

Francis and Alvitre pored over the Paxton pamphlets at the Library Company and at other institutions, paying particular attention to Quaker diaries and letters. “There are multiple sides to every story,” Francis said. “Franklin doesn’t even show up in this book. It’s not about him, or Penn, or the Quakers. It’s about the indigenous experience.”

Alvitre, a member of the Tongva tribe, mimicked the ink style used in many of the Pamphlet War cartoons by working with earth-based pigments and ink pens from the 1800s. “I want the book to convey history,” she said, “but in a way that impacts you on an emotional level because there is no skin color associated with compassion for each other.”