We all know the Academy Awards, some know the National Book Award and the Pulitzers. But few outside of the children’s book world know of the Caldecott Medal, given each year by the American Library Association to “the artist of the most distinguished American picture book for children.” Some famous winners have been Ezra Jack Keats for The Snowy Day and Maurice Sendak for Where the Wild Things Are.

A traveling exhibition is introducing this award and its honorees to the larger public. “Young at Art: A Selection of Caldecott Book Illustrations” is traveling around the country through 2024, and was on view in Houston last winter, with support from Humanities Texas. It is organized by ExhibitsUSA, using illustrations in the collection of Wichita Falls Museum of Art at Midwestern State University in Texas.

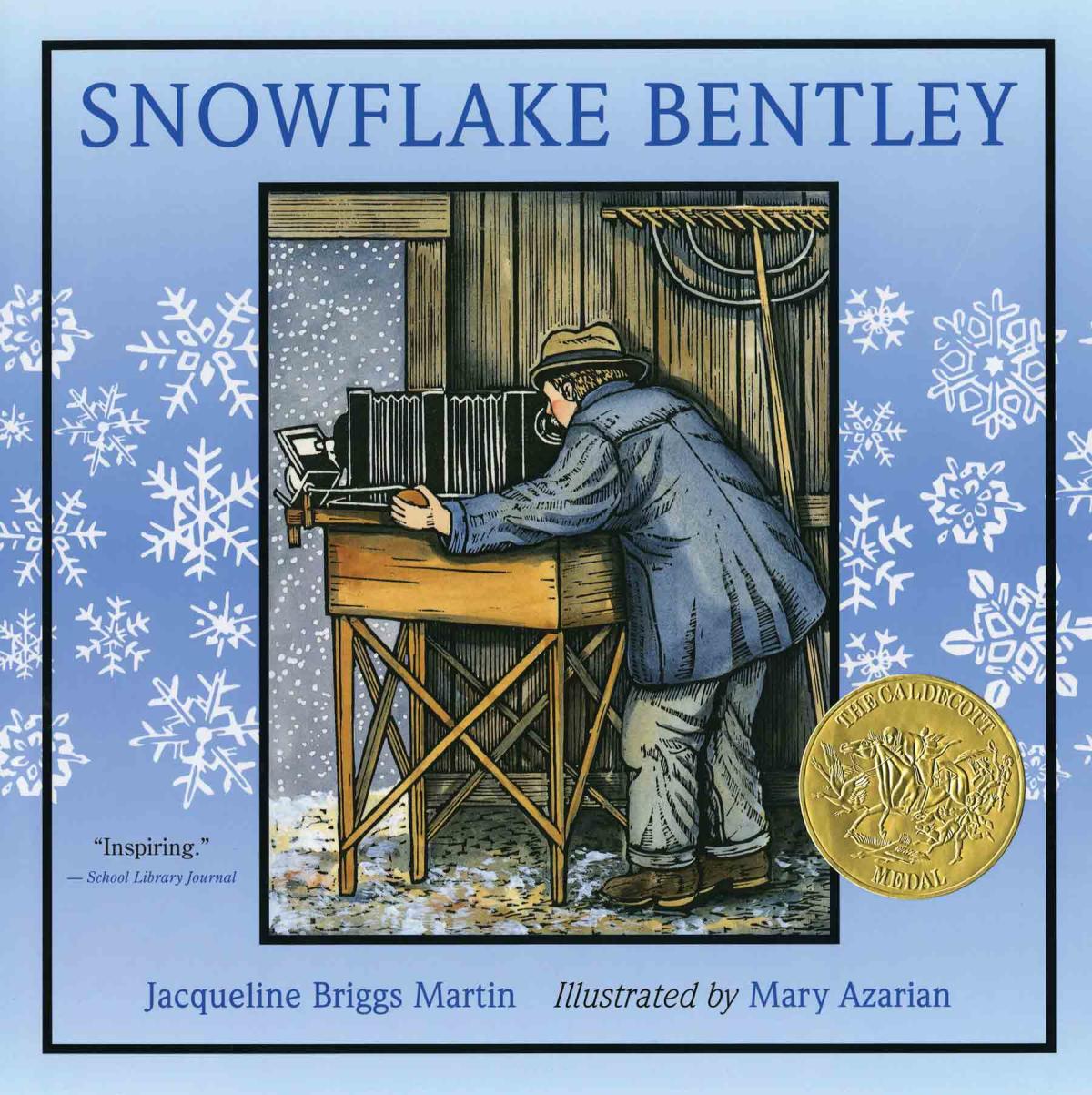

The recipient of the Caldecott Medal is the illustrator, who may or may not be the writer, too. When the illustrator is not the writer, how do artist and writer work together to create a “distinguished” picture book? Of course, there is no formula for such work. Every Caldecott-winning book has a different backstory, including the book I wrote, Snowflake Bentley.

I love words, but I cannot draw. Typically, I write the words for a children’s picture book, over many months, and send that text to an editor. If the editor accepts the manuscript, s/he is the one who chooses the illustrator. That is what happened with Snowflake Bentley (1998), a picture book about a Vermont farmer who lived from 1865 to 1931 and loved the beauty of snow crystals. First came the words. Then my editor, Ann Rider, chose Mary Azarian, a Vermont woodcut artist, to illustrate the book. A picture book is always a team effort, and the editor is an important part of the team, ensuring one consistent vision for a book.

As illustrator and writer, Mary and I did not toss ideas back and forth, talk on the phone, or collaborate directly in any active way. I did not actually meet Mary until the American Library Association convention when the Caldecott award was presented.

But I believe there was a deeper collaboration involved in the creation of Snowflake Bentley, a collaboration of spirit. Winter is Mary Azarian’s favorite season. She loves snow. So do I. In researching the book, I went to Jericho, Vermont, Wilson Bentley’s hometown, saw the camera he used to take more than 5,000 photographs of single snow crystals, studied the Jericho Historical Society’s collection of Bentley family photographs and memorabilia, talked with archivist Ray Miglionico. In researching to make the art for the book, Mary went to the same small museum, studied the same photographs, talked to the same archivist. We did the same research!

From the time I first read of Wilson Bentley in a 1979 Cricket magazine he was my hero—a man who loved the beauty of snow so much that he devoted his life to sharing that beauty. In faraway Iowa, where I live, I remembered this Vermonter every time it snowed. In her Caldecott speech, Mary said, “I had developed a great fondness and admiration for [Bentley] and I wanted to help tell his story.” Mary brought her own touches to Bentley’s world—a beautiful rendering of snow, a black and white cat (inspired by her own cat). Her work added layers of meaning to the words.

We did not need to actively collaborate. We were united in affection for Wilson Bentley and united in purpose—to tell a good story.

The nature of collaboration may vary but telling a good story is always the goal. And for my book Creekfinding (2017), telling a good story involved more active collaboration. First the story: A few years back, a man named Michael Osterholm purchased a farm in northeast Iowa. He wanted to restore the prairie. One day, a neighbor told him, “I caught trout in your cornfield when I was a boy.” Osterholm knew there must have been a creek running through the field. He determined to restore the creek to its original path. Neighbors said that would be impossible. But Mike did it. He said, “It was as if the water remembered.”

When the creek was ready, Mike added brook trout. He reported that insects came back to the creek—thousands of insects, birds came back, frogs came back. How did they find that creek? How did frogs learn there was a creek where there had not been one for five decades? I had to know the answer, had to write the story.

And this time I wanted to choose the illustrator—Iowa City scratchboard artist and long-time friend Claudia McGehee. Her passion for the beauty of nature shows in all her work. I knew she would be the perfect partner for this project. And, to my delight, she agreed. From the very beginning, this was a collaborative project. We talked with a local geologist and learned about the unique porous limestone rock in northeast Iowa that lets rainwater percolate down to form underground pools that bubble up to the surface as springs, which then create creeks.

Claudia and I studied Mike Osterholm’s slides, talked about the story. When I eventually presented the story to publishers, it was with the understanding that Claudia would be the illustrator.

After the manuscript was accepted by the University of Minnesota Press, Claudia began to do the work of illustrating. We live only a few miles from each other, so I was able to look at her work in progress—a rare treat.

We consulted, made small changes, such as removing a sidebar that cluttered a quiet prairie scene, or rearranging our telling of the sequence of trout-egg hatching—all to make the book more cohesive, more accessible to readers.

Both the making of Snowflake Bentley and Creekfinding involved trust, respect, and openness to being surprised. Our lives and our work are better when we can partake of these qualities. And these two books were better because of collaboration.

Just as two eyes give us a greater depth of vision, I believe collaboration—hearts, minds working together—results in greater depth of a story, greater understanding in every aspect of our lives.