Wonder. Conflict. Fever. Conviction. Power. Struggle. Change. Hope. Two centuries of Alabama history summed up in eight words.

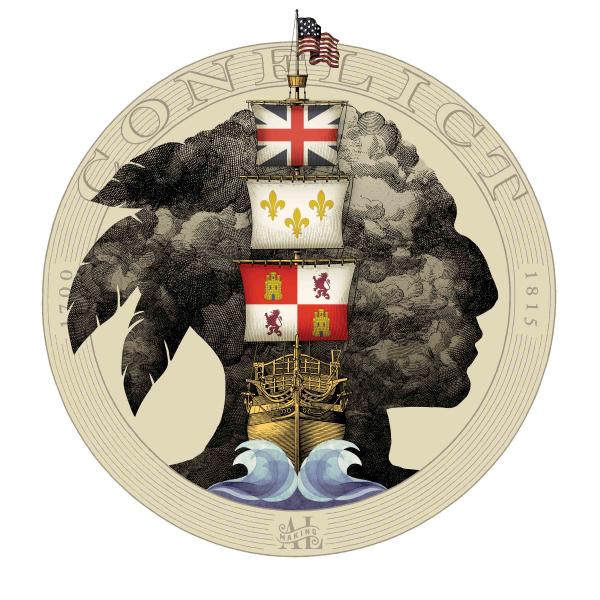

Those concepts form a storytelling framework for the Alabama Humanities Foundation’s traveling exhibit “Making Alabama,” which is journeying to each of the state’s 67 counties as part of Alabama’s bicentennial celebration. The words outline a chronological, interactive exhibit detailing periods that have defined the state, its people, and culture. For example, “conflict” describes Alabama in the eighteenth century, when France, England, and Spain all competed for a foothold in the region. “Struggle” represents the civil rights era and the United States’ fight to defeat fascism during World War II.

Laura Caldwell Anderson, director of operations for the Alabama Humanities Foundation (AHF) and curator of “Making Alabama,” spent the better part of two years compiling information for the exhibit, utilizing the AHF’s online Encyclopedia of Alabama and using visual assets—such as images of sixteenth-century pottery that had been recovered from Moundville, Alabama. Anderson, speaking as a historian and archivist, says that a chronological exhibit made sense to her.

“When we divide up the story of Alabama into themes, we fail to see that to look at the past is to see how we got where we are,” Anderson says. “Curious people don’t need a whole lot of interpretation. If they see that ‘this followed this, which followed this,’ they can draw their own conclusions about why we face the challenges we do.”

The exhibit covers some of the state’s most famous people’s stories, such as Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott, or country singer Hank Williams, who was born in Mount Olive. But it also includes some lesser-known stories, like that of Sequoyah, a Native American who created the Cherokee alphabet in the 1820s while living in what would become Fort Payne, or how 18 of the 87 delegates drafting the 1868 state constitution were black. It tells the story of the world’s largest cast-iron statue, a depiction of the Roman god Vulcan, crafted by Giuseppe Moretti for the 1904 World’s Fair, which sits atop Birmingham’s Red Mountain as a tribute to the region’s iron and steel industry. And it shows that when the black Alabamian runner Jesse Owens took home four gold medals from the 1936 Berlin Olympics, and when the black boxer and Alabama native Joe Louis knocked out German boxer Max Schmeling in June 1938, it meant more than just individual wins—they were triumphs for the entire country.

“Making Alabama” is modeled on the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum on Main Street, which sends ready-to-install exhibitions to small communities across America and encourages each locality to add their own specific stories to their programming.

“These communities buy in to being hosts,” Anderson explains. “They learn about the topic of the exhibit, they physically greet the exhibit, take it out of crates, set it up, maintain it, pack it back up—they have to be good stewards of it.”

The exhibit caretakers at Hubbertville School in Fayette County certainly subscribed to that idea while the exhibit was on display in its library in February.

High school students helped install the exhibit and fourth graders dressed up as famous Alabamians such as author Harper Lee, baseball player Hank Aaron, and author and activist Helen Keller to provide an even more interactive experience for visitors. The school produced a locally themed exhibit to run alongside “Making Alabama,” featuring photos from Fayette County’s history, birdhouses built by a community craftsman, and scorecards from 1930s pickup baseball games against the nearby rival in New River.

Hubbertville School was a natural fit to host the exhibit, says Glen Allen mayor and Hubbertville graduate Allen Dunavant, who campaigned to bring “Making Alabama” to the K–12 school. He says Fayette was one of the first counties in northwest Alabama to pass a resolution to bring the exhibit to its community.

Local students took trips to “Making Alabama” throughout its week on campus. A third-grade student on a visit to the library came away excited about sixteenth-century Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto.

“He said to me, ‘Oh my goodness, Hernando de Soto—I know all about him,” Dunavant remembers. “He started rambling off stuff. I asked him where he learned all that stuff. He said, ‘I read.’”

Anderson says she hopes “Making Alabama” will teach Alabamians, like that Glen Allen third grader, even more about their home state and inspire them to discover how diverse its ecology, economy, and population are.

Alabamians are more complicated than they sometimes let on, says Anderson. “We divide ourselves into two or three groups of people, into ways of thinking, and worry about the stereotypes people outside Alabama apply to us.”

The exhibit’s last installation, Hope, explores Alabama from the 1990s to the present, a time of reconciliation and revitalization. It cites the 2001 and 2002 convictions of the Ku Klux Klan members responsible for the 1963 Birmingham church bombing that killed four young girls. It highlights Alabama natives such as Octavia Spencer, who was born in Montgomery and is just one of two black actresses to have received three Academy Award nominations, and the Grammy-winning Alabama Shakes, a blues/rock band from Athens. As industry continues to energize the region, from the Mercedes-Benz assembly plant in Vance to Airbus’s assembly and delivery site in Mobile, the exhibit shows the state’s economic growth.

The humanities are key to conveying that message of hope, Anderson says. “They help us see one another as fully human,” she says. “If we’re going to go into our next century in Alabama and address issues that have to be addressed, we have to see one another in the context of our history and culture.

“The biggest thing I want people to take away is an interest in looking at who we want to be for the future,” Anderson continued. “The exhibit itself is about the past, but the intent is to get people to think about the future of our state and whom our state is for.”