Aviation was in its relative infancy in the late 1920s, so women flyers had plenty of opportunities to break records. In 1927, Ruth Elder was the first woman to attempt a transatlantic flight, breaking an over-water record. In 1928, Amelia Earhart was the first woman to make a full transatlantic crossing, though she regularly demurred and clarified that she wasn’t at the controls for most of the flight. In 1929, Alaskan bush pilot Marvel Crosson set the women’s altitude record, flying just short of 24,000 feet.

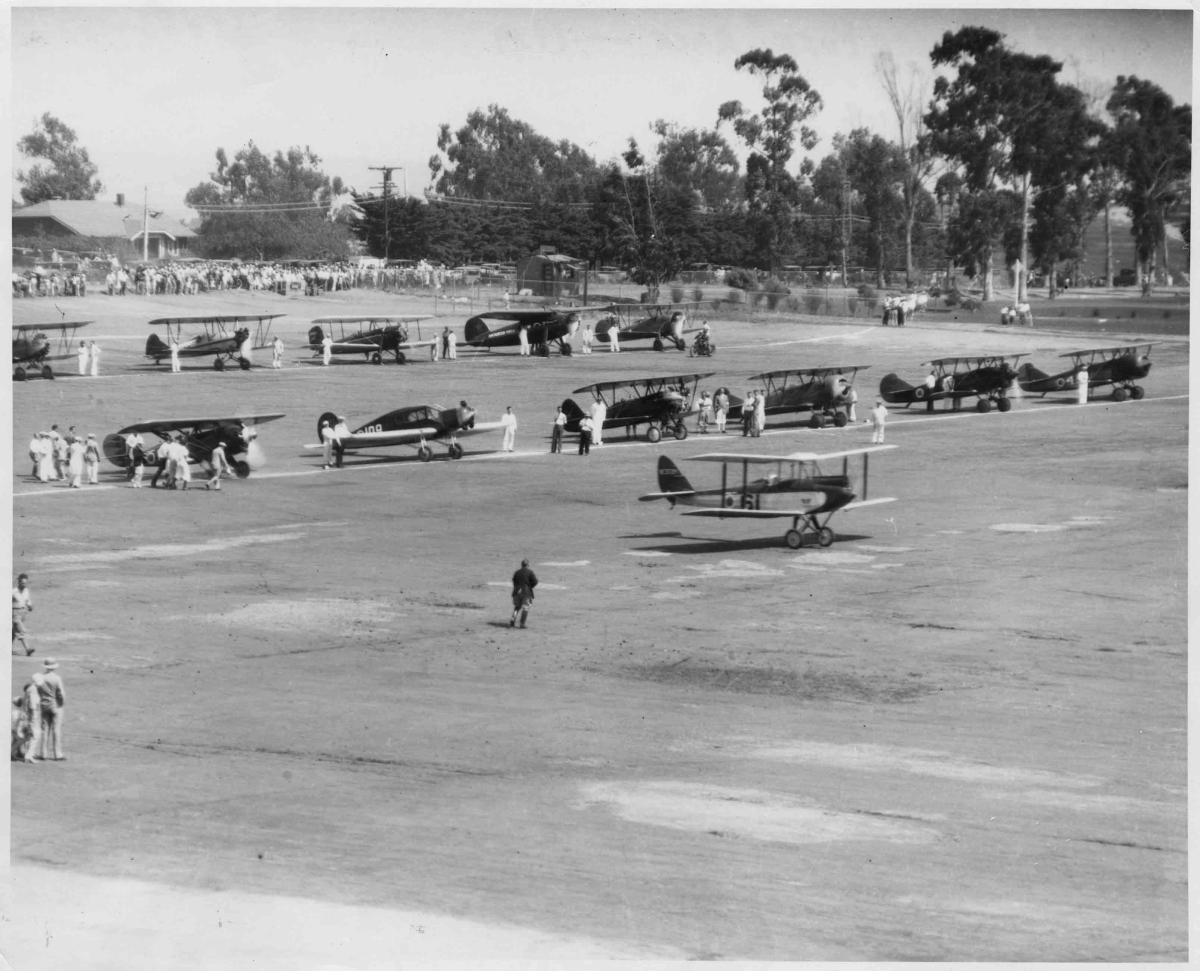

By 1929 so many women were testing boundaries that the National Exchange Club, a service organization, made a women’s air derby its national publicity project for the year. Twenty women signed on to fly a route of roughly 2,700 miles from Santa Monica, California, to Cleveland over nine days in August, making stops across the Southwest, Texas, Great Plains, and Midwest.

The women were competing for $8,000 in prize money, but the bigger stakes were convincing a skeptical public that women ought to be flying at all. Derby participants came from a range of backgrounds. Elder was a beauty queen and silent-film actress, and Earhart was the celebrated “Lady Lindy,” but Crosson was a Kansas-raised farm girl and Florence “Pancho” Barnes was a cigar-chomping wife of a minister. Phoebe Omlie and her husband, Vernon, were barnstormers who also taught flying in Memphis. (Among Vernon’s students was future Nobel Prize-winning author William Faulkner.) But they were united in their love of flying and their determination to quiet the critics. “They had a common enemy, which was the negative views of women in aviation,” says Natalie J. Stewart-Smith, an Arizona-based researcher of women flyers who lectures on the 1929 derby as part of the Arizona Humanities speakers bureau.

The flyers had an advocate in syndicated columnist Will Rogers, who covered the event. But his offhand remark on the first day of the race—“It looks like a powder puff derby to me”—was seized on by journalists and other observers who sought to diminish the race and its participants.

In light of the misogynist criticism, it’s not surprising that many of the flyers were concerned that they were being undermined in ways that went beyond negative press and sexist gossip. Before the race’s start, an unsigned note circulated among the flyers, saying, “Beware of sabotage.” Elder’s takeoff from San Bernadino was delayed when oil was found in her gas tank. Thea Rasche, a German flyer, had to make an emergency landing outside Calexico, California, and a mechanic reported that her gas line was clotted with “rubber, fibre, and many other impurities.” Not far away, the wing wires on Claire Fahy’s plane suspiciously snapped, forcing her out of the race.

“There isn’t a consensus [about sabotage], but the women did feel it would’ve been foolhardy of them not to take those suggestions seriously,” Stewart-Smith says. “Because it is their lives in the balance if something did happen.”

The worst came to pass on August 19, when Crosson’s plane crashed near Wellton, Arizona, a desert town outside of Yuma. Crosson’s body was found nearby; she had evidently jumped from the craft to her death before the crash. The likeliest explanation, according to the plane’s manufacturers, was carbon monoxide poisoning from the open-cockpit plane’s engine fumes. But the incident intensified speculation about sabotage, and critics seized on the tragedy as evidence that women were unfit to fly.

Among the loudest was Texas oilman Erle P. Halliburton, who told a newspaper after Crosson’s death that “women have conclusively proven that they cannot fly. Women have been dependent on men for guidance for so long that when they are put on their resources they are handicapped.”

Earhart, echoing the sentiment of her fellow flyers, was unbowed: “Who is this Halliburton? Who is he to pass judgment on our abilities?”

The derby was exhausting—in addition to the time in the air and all the scrutiny on the ground, the flyers were expected to attend banquets and press events at each stop. But 14 flyers successfully made it to Cleveland on August 26, with Omlie taking the prize in the light-plane class. Louise Thaden, who in 1936 would win the Bendix trophy in a New York to Los Angeles race competing against men, won in the heavy-plane class. Organizers rushed to place a horseshoe of roses around her neck. Feeling the prick of thorns on her body, she politely suggested the arrangement be placed on the nose of her plane instead.

The women were quick to take advantage of the attention the derby offered, and soon formed a group of licensed women pilots, the Ninety-Nines. (The name comes from the number of charter members.) Thaden stewarded the group in its early days, but in 1931 Earhart became its president, allowing the Ninety-Nines to build on the name of the best-known female flyer in the country. “The race was in August, and the first meeting was in November,” Stewart-Smith says. “They needed Earhart up front. She was the face people would recognize.”

Over time, the role of women pilots and the Ninety-Nines’ advocacy would change, from pushing for acceptance of women as commercial pilots (which wouldn’t happen till the 1970s) to STEM-focused advocacy today. In 1929, though, the goal was much simpler, Stewart-Smith says, “that people take the women pilots as seriously as the pilots took themselves.”