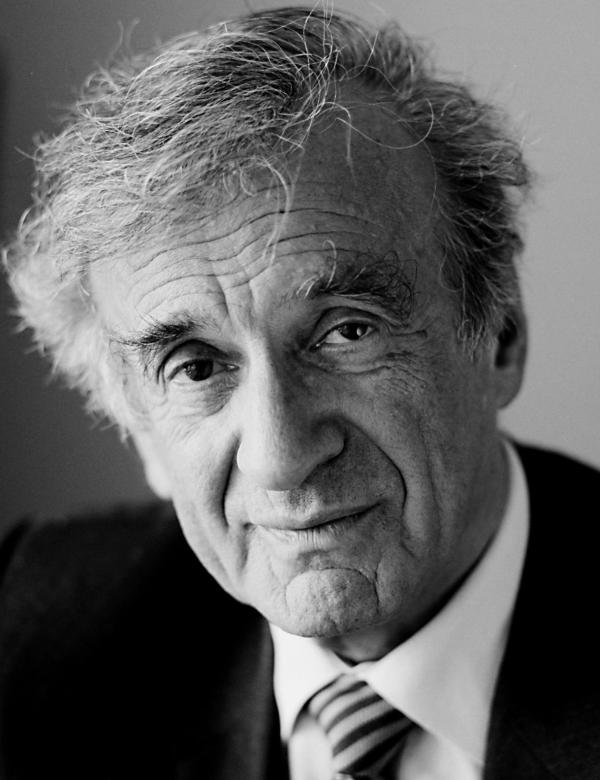

Elie Wiesel

National Humanities Medal

2009

Humanities Medalist Elie Wiesel.

—Photo by Sergey Bermeniev

Humanities Medalist Elie Wiesel.

—Photo by Sergey Bermeniev

“What does it mean to remember?” asks Elie Wiesel in his memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea. “It is to live in more than one world, to prevent the past from fading and to call upon the future to illuminate it.” For more than half a century, through his writing, his teaching, and his advocacy, Wiesel has been ensuring that the world does not forget one of its darkest moments. He bears eloquent witness to the atrocities of the Holocaust and has become a committed voice against injustice in the world today.

Born in 1928 in Sighet, Romania, Wiesel grew up in a traditional Hasidic Jewish community, where he studied Talmud every day and hung pictures of famous rabbis in his room like posters of movie stars. He describes it as a tradition that allows one to question God, even complain, while still believing that God is all powerful and all knowing. His quiet life in this small shtetl was shattered on May 16, 1944, when he and his family—his mother, father, grandmother, two older sisters, and little sister Tzipora—were packed into cattle cars with the rest of the Jews from Sighet and deported first to the Nazi concentration camp Birkenau, where his mother and little sister were murdered upon arrival, and then on to Auschwitz. He was fifteen years old. Wiesel managed to survive the next year in the camps. In the winter of 1945 he watched his father die. Weeks later, on April 11, he was rescued when the Americans liberated Buchenwald.

More than ten years later Wiesel wrote about his experience of the Holocaust. He was encouraged to by an unlikely friendship with another writer, French Nobel laureate François Mauriac. After a few years in a French orphanage with other surviving Jewish children, Wiesel studied at the Sorbonne and began working for an Israeli newspaper. As a journalist he was granted an interview with Mauriac. Wiesel’s first meeting with the great writer, and devout Catholic, was commemorated in a 1955 newspaper column by Mauriac, and again in his forward to Wiesel’s first book, Night. “That particular morning, the young Jew who came to interview me on behalf of a Tel Aviv daily won me over from the first moment,” wrote Mauriac. Their conversation that day turned personal—Mauriac sharing his memories of the German occupation and Wiesel confessing that he was one of the Jewish children Mauriac recalled being deported in cattle cars. Mauriac urged Wiesel to write about what happened and then pushed to get it printed by a reluctant publishing industry that considered the book too morbid to sell. One critic predicted that “Elie Wiesel is a one-book writer.” It was printed in Yiddish by an Argentinian press as Un di velt hot geshvign (And the World Remained Silent), and then finally in its French and English translations in 1958 and 1960. Since then it has been translated into more than thirty languages and is read as part of high school and college curricula worldwide.

Wiesel has said that “if I had not written Night, I would not have written anything else.” And the world would have been deprived of a great voice. Writing, he says, requires a willingness “to plumb the unfathomable depths of being…. Ultimately, to write is an act of faith.” Wiesel has gone on to write more than forty books, including A Beggar in Jerusalem, a Prix Médici winner; The Testament, a Prix Livre Inter winner; and The Fifth Son, winner of the Grand Prize in Literature from the City of Paris. “All my subsequent works are written in the same deliberately spare style as Night,” Wiesel writes. “It is the style of the chroniclers of the ghettos, where everything had to be said swiftly, in one breath…. Every phrase was a testament.” But invariably, he is most recognized for Night. “Books have their own destiny,” says Wiesel. “I only know that my other books are so jealous of Night. They come into my dreams that turn into nightmares, saying, ‘Why do you favor one book over us?’”

Even as a boy in Sighet, Wiesel was compelled to write. He would run off to the city hall to compose Bible commentaries on the town’s only Hebrew typewriter. Twenty years later Wiesel went back and, remarkably, found his notebook with his commentaries among other books and papers that were taken from Jewish homes and kept in a synagogue. He continued his practice of writing in notebooks and journals soon after liberation. He also continued his studies. “Every day I study Talmud,” he says. “I may be the oldest teacher around, and I might also be the oldest student around.” In fact, Wiesel continues to teach at Boston University, where he has been the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities since 1976, and has never taught the same course twice. “That’s why I have students who come for years and years and take my courses. It is an exchange of gifts, teaching.”

In 1978, President Jimmy Carter appointed Wiesel chairman of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust. The result of that commission was the building of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, which opened in 1993 and has since welcomed nearly thirty million people from around the world. “I was involved in it with every deep fiber of my being,” says Wiesel about planning the museum. The museum has placed remembering the victims of the Nazis at the center of its mission through exhibitions that offer their names, their pictures, and their personal stories, and through its ongoing research on the Holocaust and discussions of subsequent atrocities.

In 1986, Wiesel was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Nobel committee heralded him as “a messenger to mankind; his message is one of peace, atonement and human dignity…. The message is in the form of a testimony, repeated and deepened through the works of a great author.” Soon after, he founded with his wife, Marion, the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, dedicated to combating “indifference, intolerance, and injustice through international dialog.” Recently, the foundation gathered the names of forty-five Nobel laureates in an open letter supporting Iranians who dared to protest the results of their presidential election. The letter was published as a full-page ad in the New York Times and the International Herald Tribune last August. He explains, “I thought no one had the right to let them feel that they live in solitude and were abandoned by the whole world.”

By Amy Lifson