In The Gift, Lewis Hyde’s classic 1983 study of the anthropological intricacies of gift-giving, the author equates this fundamentally social act with the very root of art-making, asserting that our connection to the constantly renewed waters of creativity is carried in the fragile and intricate interpersonal choreographies that determine an artwork’s movement from one hand to another. “A work of art is a gift, not a commodity,” he neatly summarizes; “where there is no gift there is no art.”

In the late nineteenth century, when Kaiser Wilhelm II wanted to cement Germany’s diplomatic relations with the fading Ottoman Empire, he arrived bearing gifts, including a jewel-encrusted gold pocket watch decorated with a miniature portrait of himself, a large rococo clock, two nine-branch candelabra, and, a little later on, one of his personal state-of-the-art revolvers, complete with jewel-encrusted ivory handle. Not to be outdone, His Imperial Majesty, Abdülhamid II, the thirty-fourth Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, not only reciprocated with a variety of obligatory jewel-encrusted artifacts, but crated up the entire elaborately carved decorative limestone façade of the eighth-century Umayyad Caliphate palace of Mshatta—a recently excavated (in what is now Jordan) archaeological treasure of incalculable value, and perhaps the most munificent personal gift in recorded history. Certainly the heaviest shipped internationally.

The residue of this relationship—including the slightly surreal revolver with its diamond “W” monogram and a single monumental rosette from the Mshatta façade—make up just a small portion of “Gifts of the Sultan: The Arts of Giving at the Islamic Courts.” This ambitious and curatorially innovative exhibition assembles more than 225 works of art from America, Europe, and the Middle East into an engaging mosaic currently on view at LACMA (the Los Angeles County Museum of Art). Next it travels to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, for display in the fall of 2011, then on to the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar, for Spring 2012.

The basic idea is to examine more than a millennium’s worth of the history of Islam and Islamic art through a very specific social lens. “We hope that ‘Gifts of the Sultan’ will introduce new audiences to Islamic art by focusing on a practice shared by all cultures—gift exchange,” said Linda Komaroff, exhibition curator and LACMA curator of Islamic Art. While this appears at first to be a simple and elegant method for spotlighting some of the greatest achievements of artists and craftsmen throughout the Islamic world—like most cultures, Islam puts on its best aesthetic face for courtship and the reception of honored guests—it reveals the complex social circumstances underlying the creation and circulation of most artworks.

The decades-long, jewel-encrusted, one-upmanship between Kaiser Bill and Abdülhamid II, for example, served as stage dressing for an intricate political negotiation involving German military advisers and the Baghdad Railway—a web of intrigue whose fallout extended to the Armenian genocide and World War I. A radiant green velvet kaftan from sixteenth-century Iran is embossed with elaborate silver embroidery in an ornate geometric latticework studded with taboo figurative cameos—which may have been a deliberately provocative gesture when gifted by the Shah Muhammad Khudabandah to Ottoman Sultan Murad III, as it was given in the middle of a war in which Iran lost substantial territory to the Ottomans. Why send an offensive bathrobe to a foe who’s busy pummeling your armies? Plus Muhammad Shah was almost blind. What was going on here? Sometimes the negative spaces can be as compelling as the pattern itself. Two impressive, large-scale, oil-on-canvas portraits of Fath ‘Ali Shah—the ruler of Persia during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries—testify to his court’s remarkable patronage of the arts, but also to his desperation to form alliances with England and France in the wake of Russia’s aggressive annexation of Georgia. The earlier of the two portraits depicting the young, uncrowned—but already extravagantly bearded—shah was a gift to the Court of Directors of the East India Company; the later depiction, showing the shah in full regalia, was presented to Napoleon. Neither country responded, and Persia lost to the Russians twice, eventually capitulating to a series of increasingly punitive treaties. When an angry Persian mob assassinated a Russian ambassador, Fath ‘Ali sent a groveling gift of eighteen precious manuscripts and his largest jewel—the 88.7 carat Shah Diamond, which remains in the Kremlin. Gifts as decorative punctuation in sweeping historical epics of passion, tragedy, and revolution. Sweet! Well, bittersweet.

“Gifts of the Sultan” is divided into three appropriate sections: personal gifts, pious donations, and state and diplomatic gifts, and each is as remarkable for the tangled narratives they embody as for the beauty of the artifacts themselves. Almost. The sensually exquisite and formally breathtaking craft of these works tend to overwhelm any rationalizations or narrative context. The storytelling dimension remains undiminished; the aesthetic ones simply outdazzle it.

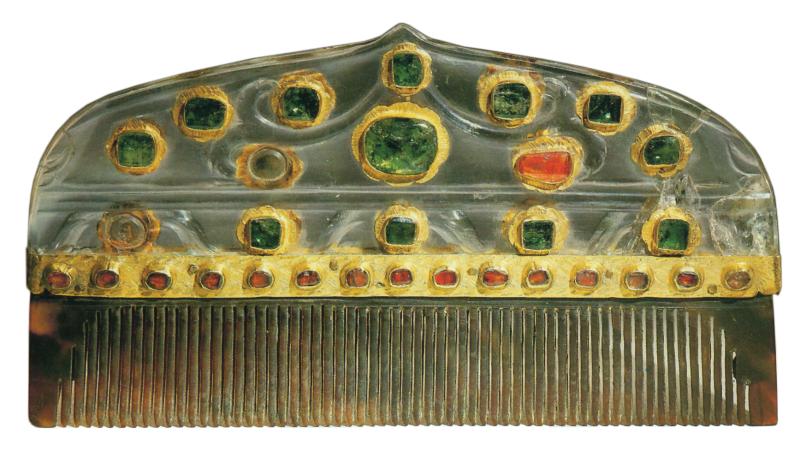

Everything is jewel-encrusted. A sumptuous late sixteenth-century Turkish comb carved from horn or tortoiseshell is set in a medieval rock crystal handle inlaid with gold and set with emeralds and rubies. An ornamental jar from the seventeenth-century Indian Mughal empire is carved from a single piece of pale nephrite jade, set in gold floral motif mounts studded with rubies, emeralds, pearls, and turquoise. Garnets and diamonds cluster amidst intricate settings of gold, silver, and bronze worked with decorative engraving, granulation and hammering in the complex, layered mathematical latticework patterning and wildly inventive calligraphic flourishes that evolved in response to Islam’s suspiciousness toward representational artwork.

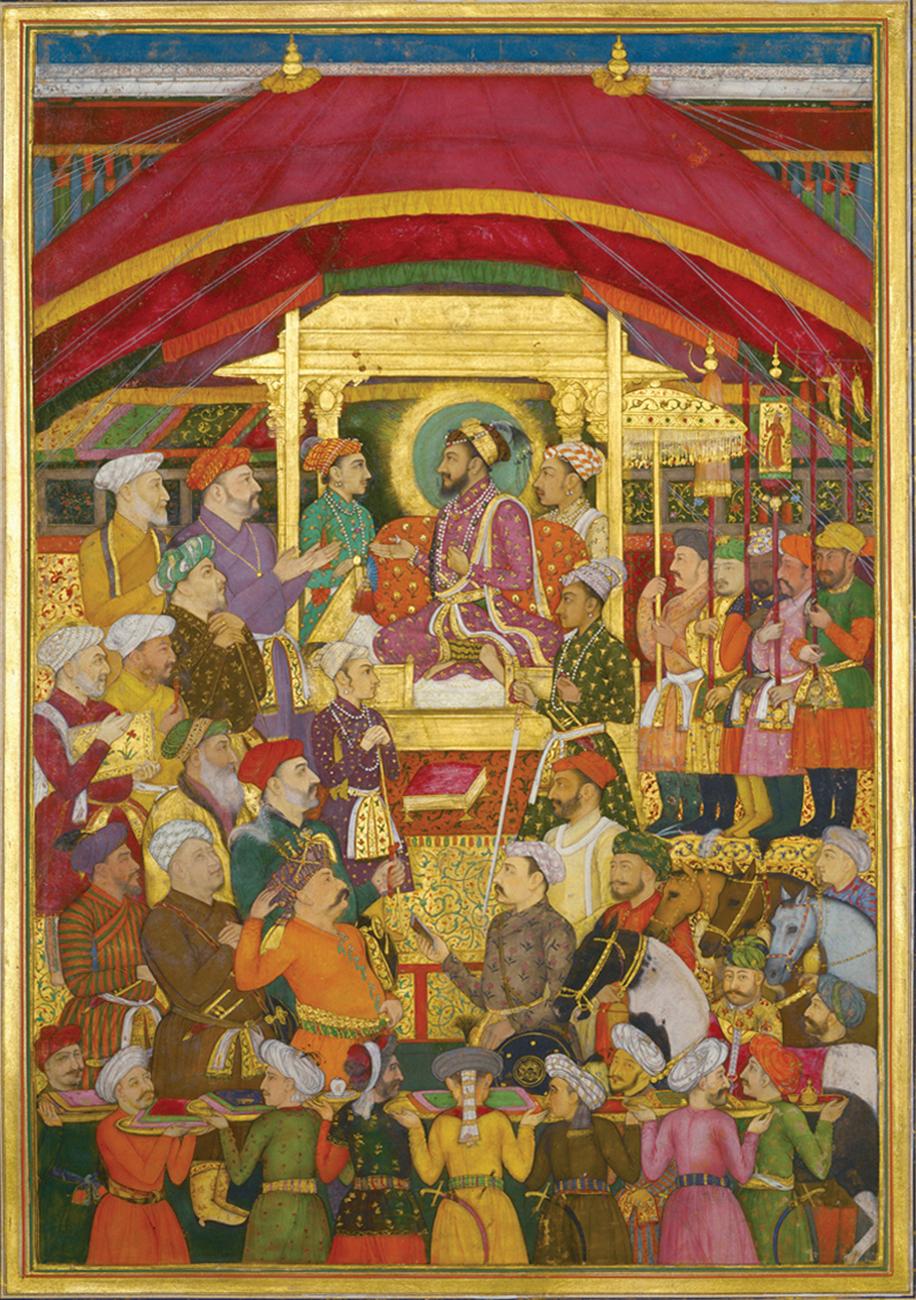

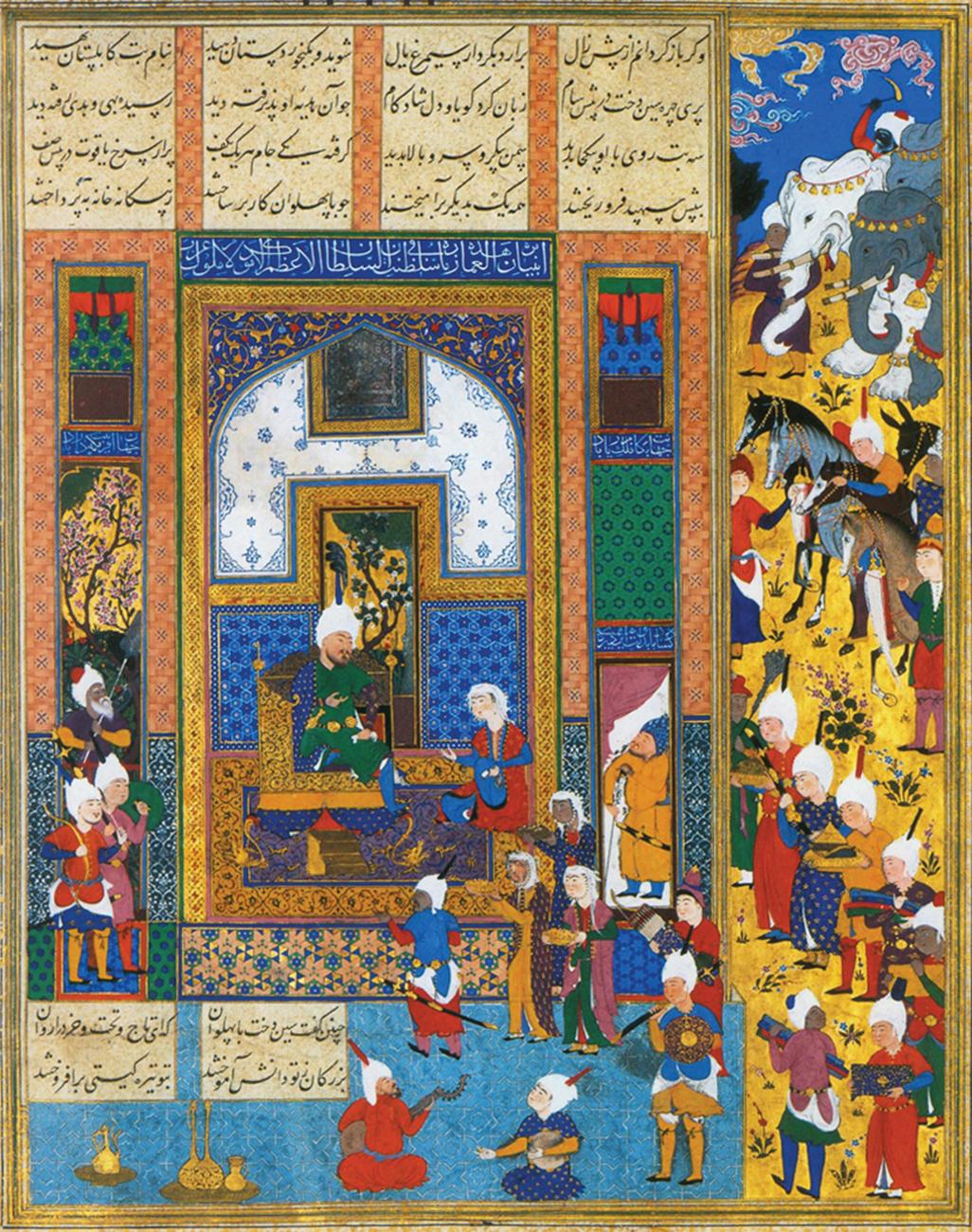

Although not rare, Islamic figurative painting is not the central measure of artistic progress or accomplishment it is considered in the West. “Gifts of the Sultan” includes many painstaking miniatures rendered in opaque watercolor—many of them depicting lavish or noteworthy exchanges of gifts, such as the fifteenth-century image of Timur (aka Tamerlane) receiving a complimentary giraffe from Egyptian ambassadors. Livestock—both the exotic and practical varieties—were among the most common gift items. Along with such desirable presents as precious aromatics, lavish displays of food, and perishable textiles like silk and leather, they are present here only in pictures.

In Islam, the most significant art practice has arguably been calligraphy, which took the lead early and eventually came to adorn virtually any available surface. There are spectacular examples of calligraphy brushed onto paper scrolls in ink made from gold and lapis lazuli, wrapped around ornate silver candlesticks, carved along the perimeter of a single section of ivory elephant tusk, inlaid into rare wood with mother-of-pearl, and engraved along the edge of a steel dagger, then inlaid with gold. Some of the most exquisite and innovative examples appear in illuminated manuscripts of the Qur’an, some dating to the first millennium CE.

While many of the most precious items in the exhibit fall into the social realms of the personal and diplomatic, some of the most impressive are spiritually motivated. Such gifts include an astounding array of lamps and candlesticks, a fabulous mosque-shaped Qur’an chest made from walnut and inlaid with ebony, ivory, and mother-of-pearl, and sections of the enormous, elaborately embroidered veil, or kiswa, that drapes the Ka‘ba—the great black cubical building that is the most sacred architectural site in Islam—and is traded out annually at the time of the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca required of the faithful. There is a simultaneous grandeur and humility in these ephemeral architectural garments—baroquely decorated skins for a minimalist monument—that outstrips most contemporary art.

Over the last decade, much attention has been paid to a field known as “Relational Aesthetics,” which posits a radical reorientation of professional art-making away from self-absorbed studio practice and into the world of interpersonal negotiations. While this has made for the serving of some very delicious meals of Thai food in gallery and museum spaces, LACMA’s thematic arrangement of undeniable artifacts delivers a knockout punch to the claim that this is anything but the underlying engine of every creative act. Drawing on twelve centuries of invention, devotion, and craftsmanship, “Gifts of the Sultan” demonstrates that an artwork and the cloud of human stories that activate its presence in the world are one and the same—you can have your jewel-encrusted revolver and shoot it off, too!