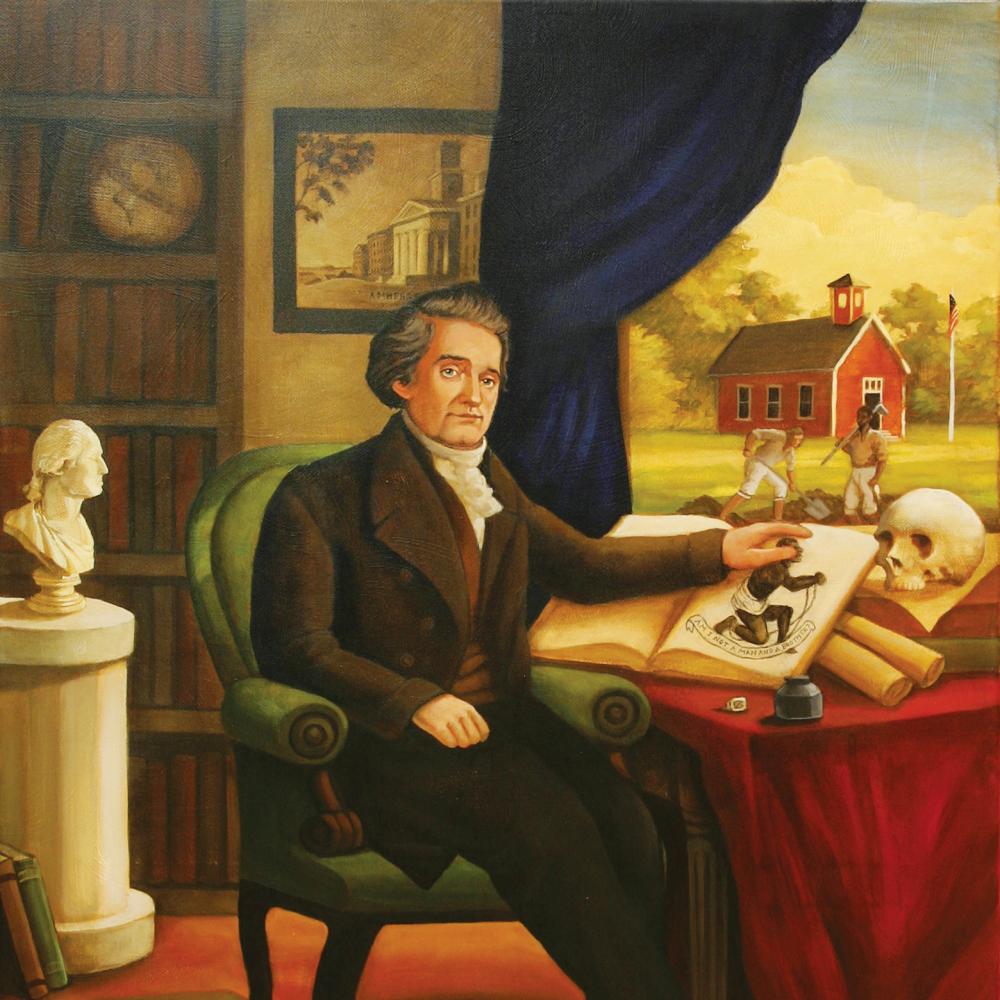

As a student at Yale and a member of the Connecticut militia during the American Revolution, Noah Webster took up the battle cry of democracy. After graduation in 1778, Webster was convinced the only way to unite the fledgling republic was through a common language and public education.

“Webster viewed education—specifically language and spelling—as part of nation-building,” says Christopher Dobbs, executive director of the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society. With the support of the Connecticut Humanities Council, the society has added educational programs and a new section called Noah’s Discovery Learning Space. “He feared that without an educated populace and a common language, the noble experiment of the United States might disintegrate. Creating a national identity was fundamental.”

While working as a schoolteacher after the war, Webster decided that every child in the new country should speak and spell the same way. He complained that American schools used textbooks, such as A New Guide to the English Tongue by Thomas Dilworth, an Englishman, that taught only English geography and English history. Webster was determined that American schoolchildren learn about American authors and heroes.

He also wanted spelling to be more phonetic, making it easier for children to learn. In 1783, he published volume one of A Grammatical Institute of the English Language, also known as The American Spelling Book, or the Blue-Backed Speller for its identifiable blue paper cover.

“Today, Noah Webster is best known as the author of the American Dictionary,” says Dobbs. “But A Grammatical Institute of the English Language was one of the most popular and influential series of textbooks ever published in America.”

Webster focused on three rules: dividing words into syllables, proper pronunciation, and correct spelling. “Many of his changes were not embraced by Americans, but others survive to this day such as striking the “u” in such words as humour, rumour, colour, etc. and in altering words such as theater (replacing the “re” ending with an “er”) and music instead of musick,” says Dobbs.

Others did not catch on, such as changing “tongue” to “tung.” To his speller, he also added precepts about George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and capitals and counties of each of the thirteen states.

To promote his “American books for American children,” Webster traveled from town to town, meeting with university heads and politicians, asking each to publicly declare his book superior to others. Many complied, including Joseph Willard, president of Harvard University, who wrote in 1784: “I Received, some time ago, three copies of your Grammatical Institute of the English Language. I have perused it myself, and put into the hands of several friends for their perusal. We all concur in the opinion, that it is much superior to Mr. Dilworth’s New Guide; and that it may be very useful in Schools.”

Webster also thought American children should be schooled in moral and civic values. One chapter of the speller titled “Lessons of easy Words, to teach Children to read, and to know their Duty” includes: “I will not walk with bad men; that I may not be cast off with them. I will love the law and keep it. I will walk with the just and do good.” Another said, “Be a good child: mind your book; love your school, and strive to learn.”

Webster later wrote that his intent was “to furnish our schools with a tolerably complete system of elementary knowledge in books of my own, gradually substituting American books for English, and weaning our people from their prejudices and from their confidence in English authority.” Webster never stopped improving his speller, revising it many times during his lifetime. It’s estimated that nearly 100 million copies were sold, used in homes and schools from 1783 through the early 1900s.

“I believe that Webster is one of America’s forgotten founding fathers,” says Dobbs. “While others attempted to create a country through war and politics, Webster did it largely, but not exclusively, through education. He once wrote that ‘in our American republic, where government is in the hands of the people, knowledge should be universally diffused by means of public schools.’ Webster realized that through education you can help shape a country’s values, ideas, and belief structure.”