“All great movements have their historians. Some of them have their poets. At least one has had its sculptor. Mrs. Adelaide Johnson is the sculptor of the movement for the emancipation of women.”

—Washington Post, April 4,1909

In November 1939, the New York Times ran an unusual story about an elderly woman who destroyed more than $100,000 worth of marble sculptures with a sledgehammer. The woman was Adelaide Johnson, the so-called “Sculptor of Suffrage,” and the sculptures were the busts of prominent women that Johnson had lovingly cast in white Italian Carrara marble.

For more than fifty years, Johnson had dedicated her life and whatever money she had to fulfill her dream of creating a “Gallery of Eminent Women.” But, as she explained to reporters, “swivel-chair museum experts” refused to accept her work, and now, at eighty, she was about to lose her unheated house for failing to pay property taxes. Unable to find buyers for her “white children,” as she called the statues, she decided to demolish them. Then she invited reporters to her home studio in Washington, D.C., to survey the damage.

“Chunks of marble . . . littered the floor,” the Times reported, evidence of more than a dozen statues that had been beheaded or otherwise maimed. Though she enlisted a younger friend to wield the sledgehammer, Johnson issued the order, promising to destroy every piece within the week.

Johnson’s house was located at 230 Maryland Avenue, N.E., just two blocks from the U.S. Capitol, where her most famous statue resided in the storage area known as “the Crypt.” Despite her earlier artistic success, by 1939 she faced eviction, homelessness, and obscurity. Countless artists have suffered for their craft, but few have suffered as much as Adelaide Johnson and for so little reward. Her fate speaks to the challenges facing female artists throughout time, but even more so to our collective refusal to take seriously women’s contributions to American history.

Johnson lived through the peak era of American civic commemoration. She watched as dozens of monuments were erected to Civil War veterans in the nation’s capital, and she witnessed the construction of both the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial. She corresponded with the leaders of the brand-new Smithsonian National Museum, and she petitioned the National Gallery of Art to buy one of her pieces as soon as it opened. She felt naively confident that women would be included in these emerging national shrines. In 2020, as we contemplate the suffrage centennial and the meaning of public statuary, women’s place in our shared national story is still far from secure.

Sarah Adeline Johnson was born in 1859 on a farm in Plymouth, Illinois. The Johnsons raised sheep for wool, which they spun into cloth to sell, and by age ten Sarah was making the family’s clothes. Her artistic talent surpassed sewing, and her parents saved enough money to send her to the St. Louis School of Design, opened by suffragist Mary Foote Henderson to “enable women to earn their own livelihood, and promote a more general appreciation of art.” Sarah earned top prizes, but she remained frustrated by the contrast between her talents and her limited options. In the hope of becoming a professional artist, she changed her name to Adelaide, which she thought had more flair, and moved to Chicago in 1879 to attend the Chicago Art School. Immediately upon arrival, however, she lost her entire savings to a pickpocket and opened a decorative arts firm instead.

After triumphing over many hardships in her first 20 years, Johnson took as her motto “Know what you want and you will surely get it.” But she never could have anticipated the windfall that enabled her to train as a sculptor in Italy. One morning in January 1882, as she rushed to her studio in the Central Music Hall, Johnson stepped into an open elevator shaft and fell 20 feet. Her fractured skull and leg bones required months to heal, and her right leg shrank more than three inches. Rather than accept the small settlement offered by the building owners, she took them to court and won a remarkable $15,000. With her cane in hand, Johnson left for Europe in June of 1883, the first of nearly 30 such voyages.

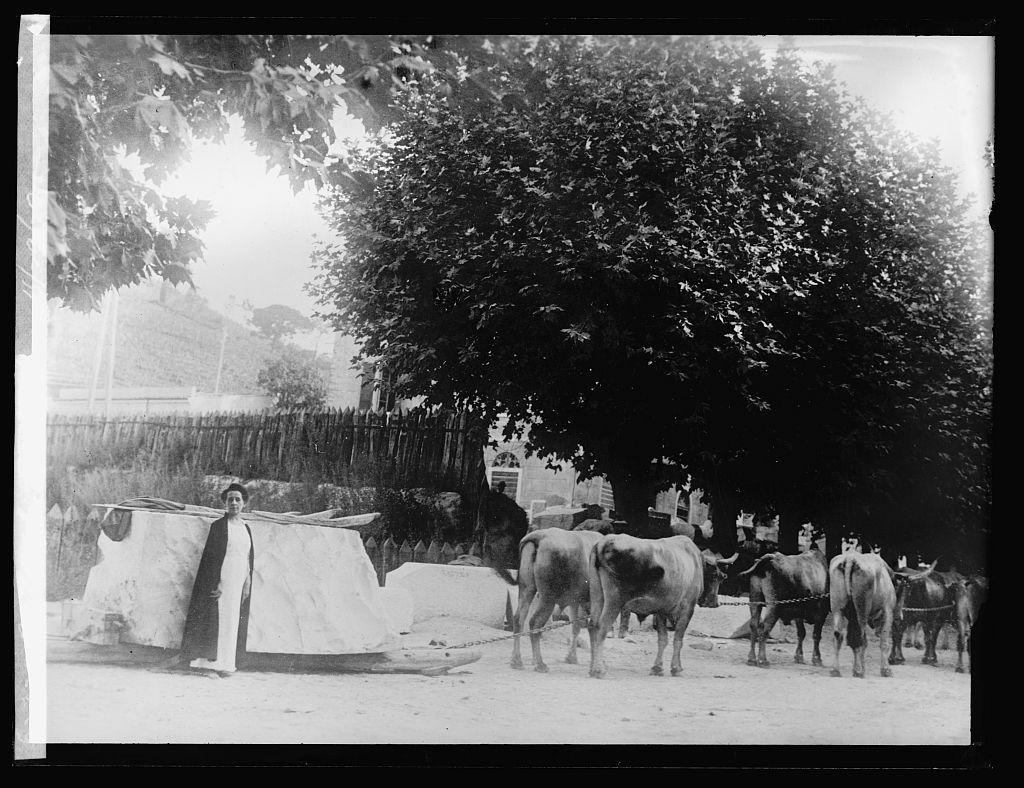

To be a female artist in the nineteenth century was challenging enough, but to be a female sculptor was nearly unthinkable. For starters, sculptors required familiarity with human anatomy, presumably of both sexes, which no respectable woman was to have. Secondly, sculptors had to work with heavy materials, such as blocks of marble weighing many hundreds of pounds. Johnson herself stood barely five feet tall and weighed just one hundred pounds, many times less than her future creations. Nevertheless, a few intrepid American women wound their way to Italy and became sculptors, only to be dismissively dubbed “the white, marmorean flock” by the writer Henry James.

Once in Rome, Johnson befriended Harriet Hosmer, the leader of the so-called flock, and Hosmer became, Johnson said, “a kind of fairy godmother.” Next, Johnson convinced the famed Italian sculptor Giulio Monteverde to take her on as his sole pupil. From him, she learned the neoclassical techniques of sculpture, including modeling from life, molding casts in clay, selecting marble, and working with stonecutters to create the finished pieces. But Johnson dissented from her mentor’s commitment to realism, claiming that by intuiting her subject’s innermost selves she could create busts not of the real but of the ideal.

In 1886, Johnson returned to the United States and rented a room in Washington, D.C., just months after completion of the Washington Monument, then the tallest building in the world, and just in time to watch as the nation turned its attention to commemorating the Civil War. Indeed, the vast majority of Civil War statues, Union and Confederate alike, were built between the 1880s and the 1920s. Johnson hoped to participate in this sculptural bonanza. Her sister-in-law Sadie sent her a news clipping announcing the open call for proposals for the memorial at Ulysses S. Grant’s tomb in Manhattan. The commission went to the architect John H. Duncan, who modeled the design on the ancient Mausoleum of Halicarnassus in Turkey. An estimated 90,000 individuals from all over the world contributed more than $600,000 to create what remains the largest mausoleum in North America. On the day of the monument’s dedication, more than one million Americans came to pay their respects, and Grant’s Tomb remained the most visited spot in the nation for decades.

Johnson’s first commission was to craft a bust of Union general and U.S. senator John Logan, but that would be the extent of her Civil War statuary. By the end of the decade, she had found a new market: She would be the sculptor of suffrage.

In Washington, Johnson boarded with Ellen Sheldon, the secretary of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). Sheldon introduced Johnson to Susan B. Anthony, the patron saint of the suffrage movement, and suggested that Anthony sit for Johnson to sculpt. Anthony immediately agreed, and even stayed on in Washington several extra days after Johnson’s clay model was accidently ruined, the first of countless such mishaps that would plague Johnson throughout her career. Then, Johnson traveled to Italy to carve the bust in marble. It was displayed at the 1887 NWSA meeting to great acclaim.

While she thrived in Washington’s social scene—attending literary and art events; giving lectures on the philosophy of Francois Delsarte, whose insistence that an artist must understand their subject’s inner emotions Johnson adopted as her own; joining the Vegetarian Society and NWSA—Johnson hustled to pay her bills. She found few buyers for her sculpted busts, for which she charged $1,000. For several months in the late 1880s, she worked as a “computer” for the U.S. Census but was let go after she requested several days off to attend the annual NWSA meeting. She also took in sewing, taught art classes, lectured, sold pamphlets extolling her vegetarian philosophy, and offered to lead a European tour for young American women whose parents wanted their daughters to be cultured but also chaperoned.

Johnson believed that her big break was to come in 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Suffrage leaders agreed that her bust of Susan B. Anthony should go on display in the Gallery of Honor in the Woman’s Building, accompanied by busts of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and the physician Caroline Winslow. Johnson spent several weeks at Anthony’s home in Rochester, New York, with Stanton as her model, and then traveled to Italy to complete the works. One of the clay molds was destroyed on route, and two of the statues had to be redone because of abnormalities in the marble. Due to a shipping error, the busts failed to make it to Chicago in time for the opening of the World’s Fair and then were further delayed when exhibitors refused to provide stands, telling Johnson that she could place them on shelves on the second floor. Johnson held her ground, and by July her statues framed the ornate fountain, by sculptor Anne Whitney, in the Gallery of Honor.

Never before had the world seen the sculpted busts of accomplished women so prominently displayed. Johnson hoped that viewing women in this new light would force people to appreciate women’s contributions and their future potential as full citizens. While she referred to her sculptures as her “white children” in reference to the marble color, they were also all of white people. Mainstream suffrage organizations discriminated against African-American women—who led the charge for universal voting rights through churches, black women’s clubs, and civil rights organizations—and it likely did not occur to Johnson to include black women in her statuary. The exhibits at the World’s Fair also excluded black citizens, prompting Ida B. Wells to distribute a pamphlet in protest. Timed to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in North America, the 1893 World’s Fair promoted a triumphalist narrative of white America on the world stage.

Inspired by the exhibits in the Woman’s Building, Johnson returned home to Washington, “the only American city for me,” determined that women should be represented in the grand-scale national narratives just then being constructed. She avidly followed the progress of the Smithsonian Institution, which would house several of the exhibits from the World’s Fair, and wrote to Franklin Smith, the man spearheading an effort to build a National Gallery of History and Art. Smith described his plan as “an American Walhalla,” representing the “intellectual development of a nation” and rivaling the Louvre and the Vatican in significance. But he was not interested in including women and sent Johnson a perfunctory reply.

Undaunted by Smith’s brush-off, Johnson wrote May Wright Sewall, who had organized the World’s Congress of Representative Women at the fair, to outline her plan. “The expectation is to start or found here at Washington a national portrait gallery of eminent women,” Johnson explained. “While I hope certainly to do many portraits of people not eminent and who will have no place in that thought, my first and best efforts now are to secure those who have blossomed in this wonderful age while they are here and at their best moments.” The problem, of course, was sponsorship: Who would commission a bunch of sculptures of women?

Over the next several years, Johnson reached out to prominent women across the country and completed many busts. She even contacted the Library of Congress to request a list of books on women to help her identify possible patrons. But she received many more rejections than contracts. Compounding matters, after the conclusion of the 1893 World’s Fair, Johnson engaged in a decades long dispute with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (which NWSA became in 1890) over the ownership of the busts of the “Great Three,” Anthony, Stanton, and Mott.

Their original agreement contained a questionable stipulation that Johnson would retain possession of the busts until they could be placed in the Capitol Rotunda. But no one had secured permission for the busts to go there, and Anthony herself did not want them in the Capitol. Anthony thought the busts “would seem infinitesimal by the side of the heroic figures,” and she especially objected “to the atmosphere of tobacco, spittoons, and the class of men who roam around [the Capitol Rotunda].” She preferred the busts go to the Library of Congress, a “beautiful building, amid surroundings of books and pictures.” In 1904, Anthony and her close associate Ida Husted Harper wrote Johnson a series of increasingly heated letters demanding that the matter be settled before Anthony died. Harper told Johnson that if she did not accede to the compromise plan, she would “have to bear the burden of letting Miss Anthony go to her grave with her last wish unfulfilled.” Johnson refused to budge.

Johnson’s personal life was as tumultuous as her professional life. She regularly squabbled with her friends and once sent Harper at NAWSA a letter that was 64 pages long. Although her brother Charles sent her money, he too received long howlers from Adelaide. Her most emotional correspondence, however, was with Alexander Jenkins, the man to whom she was married for 12 years.

Johnson met Jenkins, who was British, after he attended one of her lectures. The two exchanged passionate letters for two years before marrying in 1896. Johnson planned the elaborate all-white ceremony to coincide with the annual NAWSA Convention so that Susan B. Anthony could be there. The ceremony took place at Johnson’s home studio, with sculptures and suffragists both in attendance. In a gesture without precedent, Jenkins, who was 12 years her junior, took Johnson’s last name. Her friend Anne Henderson observed, “as in other aspects of her life, Johnson refused not to try the impossible.” Due to financial insecurity, the couple rarely lived in the same place and divorced in 1908.

In the summer of 1909, Johnson’s fortunes seemed like they might turn when the millionaire suffragist Alva Vanderbilt Belmont toured her New York studio and offered to buy replicas of the busts of the “Great Three” for $2,100. Though Johnson was disappointed that “my three precious marbles are to go to one of the richest women in the world for the price of one,” she accepted the offer. Belmont displayed the busts in her Madison Avenue mansion and soon commissioned a bust of herself. After Johnson’s long dispute with NAWSA, she eagerly joined forces with NAWSA’s rival group, the National Woman’s Party (NWP), led by Alice Paul and largely funded by Belmont.

After the Nineteenth Amendment passed Congress in 1919, the NWP approached Johnson about making replicas of the Great Three to be placed, finally, in the Capitol Rotunda. Johnson enthusiastically agreed and imagined her sculptures opposite the imposing bust of Abraham Lincoln. Several days later, Johnson set sail for Italy to complete her vision, thirty years in the making.

With the grandeur of the Lincoln statue in mind, Johnson selected an eight-ton block of marble in Carrara and wrote Paul that she would need to double her estimated cost to $4,000. For the next five months, Johnson labored in an unheated studio with no water and no toilet. Her goal was to complete the statue in time for the elaborate ratification party Paul had planned for February 15, 1921, what would have been Susan B. Anthony’s one-hundred-and-first birthday. Johnson and her statue—now one colossal monument of all three women—survived three earthquakes, numerous marble cracks, and one national railroad strike to meet this ambitious deadline. The only hitch was that no one had yet secured permission for The Portrait Monument, as it was now called, to be displayed in the Rotunda.

The Portrait Monument arrived at the Capitol on February 4, 1921, but congressional officials refused to allow it inside. After several days, Paul secured permission for the statue to be placed in the Rotunda only by agreeing that it could be moved after the celebration. The Portrait Monument was placed between the busts of Ulysses S. Grant and Lincoln, just as Johnson had hoped. She reflected that “we arrived as planned . . . and the first monument of women to womankind done by a woman presented by women for women was placed in the Capitol of the nation.”

Newspapers from across the country reported on the unveiling ceremony, one thousand women crowded inside the Rotunda, while at least a thousand more stood outside, and everyone wanted to speak to the sculptor. As soon as the ceremony concluded, however, work crews arrived to move the statue, which critics denigrated as “three ladies in a bathtub,” downstairs to the storage area known as the Crypt.

Nevertheless, Johnson relished the fact that her statue was finally inside the Capitol, and she held out hope that her Gallery of Eminent Women would eventually become reality. In 1926, a benefactor gave her the money to buy the house on Maryland Avenue. She lived upstairs and displayed her statues downstairs in her own makeshift gallery. Johnson continued to entertain visitors and seek press, and, as she had done for most of her adult life, she lived without heat or much food because she could not afford the expense.

In 1939, after receiving an eviction notice, Johnson determined to destroy her statues. Her desperate stunt worked, and Congressman Sol Bloom of New York paid off her debts, enabling Johnson to remain in her home. Then, in 1950, Senate Bill 3328 proposed that the federal government purchase her house and its contents, which included not only her statues but also many artifacts of the women’s movement, so that it could become a museum maintained as a “national monument in honor of womankind.” One of several bills proposed to sustain Johnson and her gallery, it was never voted on.

The Portrait Monument remained in the Crypt until 1997, when women’s groups succeeded in raising the necessary funds and passing legislation to move it back upstairs to the Rotunda, despite significant congressional opposition and widespread concern that the statue omitted women of color. That same year, Karen Straser, a leader of the group responsible for moving the statue, founded the National Women’s History Museum (NWHM), a modern successor to Johnson’s Gallery of Eminent Women. For more than 20 years, the NWHM has lobbied for the creation of a women’s history museum. In 2014, Congress appointed a bipartisan commission to study the issue and, in February 2020, the House of Representatives overwhelmingly passed the Smithsonian Women’s History Museum Act to create a new museum on or near the Mall. In addition, the National Portrait Gallery had planned to commission a new, more inclusive suffrage statue in 2020, but these plans are now on hold indefinitely due to the pandemic.

Johnson died in 1955, penniless and living with a younger member of the NWP. Many of her remaining statues went to the Smithsonian and her voluminous papers, themselves a rich archive of suffrage history, are held by the Library of Congress. One of the women whose bust Johnson sculpted was Helen Hamilton Gardener, the “fallen woman” who reinvented herself and became the “most potent factor” in congressional passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. In her final speech, given just three months before she died in 1925, Gardener pondered how suffragists would be remembered. The event was held near many of the newly erected Civil War statues and within view of Arlington National Cemetery, which Gardener described as the “great city of the dead heroes of many wars.” Our Arlington, Gardener intoned, “is scattered over America in graves little recognized where lie the great commanders of the bloodless revolution that freed womankind.”

Adelaide Johnson is buried at the historic Congressional Cemetery in Washington, just a few blocks from her most famous statue. During her lifetime, she witnessed the nation craft the stories that we still tell about ourselves today in museums, in monuments, and in textbooks. Given her proximity to the making of these stories, her feminist ideals, and her artistic talent, Johnson worked tirelessly, thanklessly, and often erratically in the hope of securing for women a central place in our shared narratives. In 2020, as many suffrage centennial events have been postponed and as we continue to debate the meaning of our national statuary, perhaps a fitting tribute would be to visit Johnson’s grave and pay our respects to the Gallery of Eminent Women all around us in graves little recognized.