150 Years Ago: Compensated Emancipation

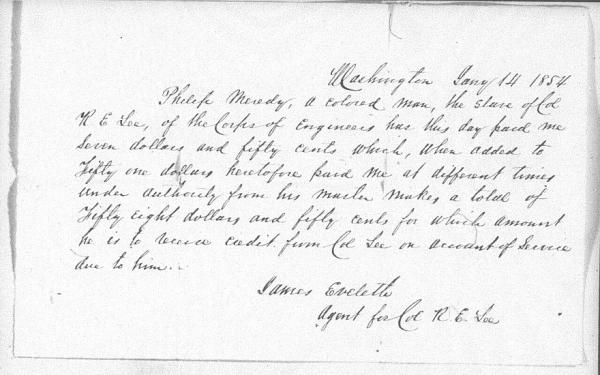

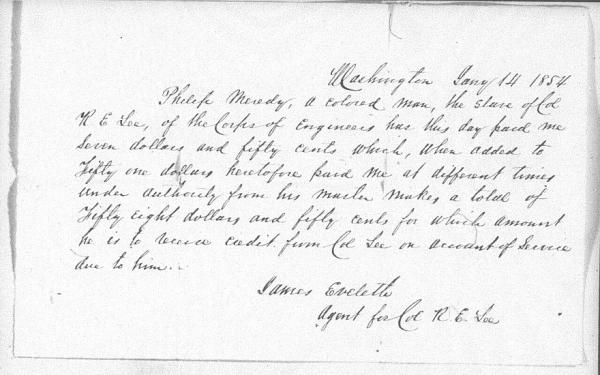

Claim regarding Philip Meredith, slave of General Robert E. Lee

US National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

Claim regarding Philip Meredith, slave of General Robert E. Lee

US National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

Records posted online this week present an emerging portrait of the 3,000 slaves who lived in the District of Columbia in 1862, making broadly accessible for the first time an official account of the name, approximate age, gender, and, sometimes, occupation of a substantial community of enslaved Americans near the start of the Civil War.

The documents record the often painful history of the implementation of the Compensated Emancipation Act, which ordered all slaves in the District of Columbia to be freed and their owners compensated. A huge bound volume recording the activities of D.C. commissioners charged with carrying out the law lists eighteen-year-old Mary Finick, for example, as a “stout healthy girl, [who] has not been confined to her bed a day since I have owned her, which has been upwards of seven years. “

The act was the first time the government had officially liberated any group of slaves, said U.S Archivist David S. Ferriero. The Emancipation Proclamation, which freed slaves in the 10 states then in rebellion, followed eight months later.

"Slaves at that time were generally anonymous," said Kenneth Winkle, a University of Nebraska-Lincoln history professor and co-director of the Civil War Washington project. "In the 1860 census, for example, Southerners objected to providing their slaves’ names as if it would make them more real, more human."

To date researchers have put online 200 of the roughly 1,000 petitions filed in D.C. by slave-holders seeking compensation in exchange for their slaves' freedom. These records provide exceptionally rare documentation of an entire community of African Americans, said Winkle. "It is a remarkable story, largely overlooked."

Digitized under a grant provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities to the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at Nebraska, Lincoln, the original records were displayed at a press conference in Washington, D.C. to mark the 150th anniversary of the passage of the Act.

The documents date from a period soon after President Abraham Lincoln signed the act on April 16, 1862. Washington D.C. commissioners accepted petitions from slave owners for compensation. They hired a slave dealer from Baltimore to provide an outside evaluation of their “value”—although the market for slaves had entirely collapsed with the coming of the Civil War, according to Winkle. Philip Reid, the skilled workman who figured out how to install the statue "Freedom Triumphant in War and Peace" on the top of the Capitol, was valued at $1,500. Other individuals, presumably small children or the infirm, were listed as having "no value."

Speaking at the press conference, Archivist Ferriero said digitization of papers related to the Compensated Emancipation Act should occur as fast as possible to ensure that the history of this important chapter in American history can be studied by scholars and the public.

Winkle said the records “can be, at points, horrible to read. And the physical descriptions are just one example of what [the slaves] went through. These documents show in real, human terms what slavery did to people, and then, what freedom would mean when they were released.”

For more information see:

“D.C. Emancipation Tallied the Price of Freedom,” The Washington Post

“National Archives Shares Rarely-seen Slave Petitions DC Emancipation Act,” National Archives

“UNL Study of Emancipation Documents Reveals Rare Look Into Slave’s Lives,” University of Nebraska-Lincoln

*For a fuller explanaton of the petition of Philip Meredith, above, see this National Archives video.