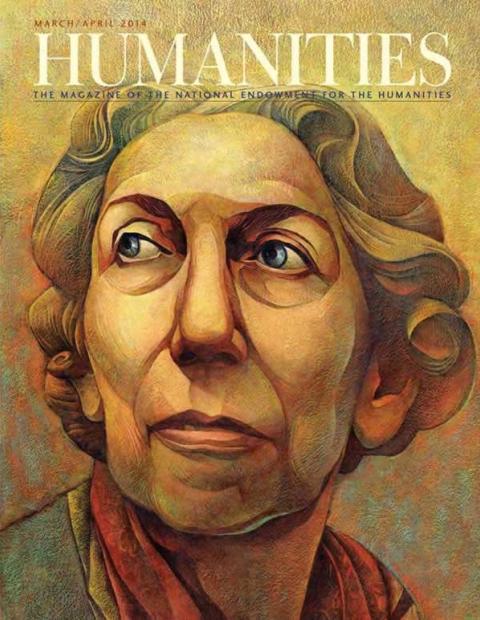

Like Robert Frost, Carl Sandburg, and a few others, Eudora Welty endures in national memory as the perpetual senior citizen, someone tenured for decades as a silver-haired elder of American letters. Her abiding maturity made her seem, perhaps long before her time, perfectly suited to the role of our favorite maiden aunt.

But when I visited Welty at her Jackson, Mississippi, home on a bright, hot July day in 1994, I got a glimpse of the girl she used to be. She was eighty-five by then, stooped by arthritis, and feeling the full weight of her years. As she slowly made her way into her living room, navigating the floor as if walking a tightrope, I could see that her clear, blue eyes retained the vigorous curiosity that had defined her career. She still wanted to know what would happen next.

And while she sat with me for one of her last interviews, Welty seemed acutely aware that she had been young once—and slightly surprised, like so many people touched by advancing age, that the seasons had worked their will upon her so quickly.

Physical decline had kept Welty from the prized camellias planted out back, and they were now forced to fend for themselves. “The garden is gone. It makes me ill to look at it,” she told me in her signature Southern drawl. “But I’m not complaining. It’s just the state of things.”

Welty’s comment about the sad state of her yard was just a passing remark, and yet it appeared to point toward the center of her artistic vision, which seemed keenly alert to the way that time pressed, like a front of weather, on every living thing.

What Welty once wrote of E. B. White’s work could just as easily describe her literary ideal: “The transitory more and more becomes one with the beautiful.” Her three avocations—gardening, current events, and photography—were, like her writing, deeply informed by a desire to secure fragile moments as objects of art.

Tellingly, One Writer’s Beginnings, Welty’s celebrated 1984 memoir, begins with a passage about timepieces:

In our house on North Congress Street in Jackson, Mississippi, where I was born, the oldest of three children, in 1909, we grew up to the striking of clocks. There was a mission-style oak grandfather clock standing in the hall, which sent its gong-like strokes through the living room, dining room, kitchen and pantry, and up the sounding board of the stairwell. Through the night, it could find its way into our ears; sometimes, even on the sleeping porch, midnight could wake us up. My parents had a smaller striking clock that answered it. . . . This was good at least for a future fiction writer, being able to learn so penetratingly, and almost first of all, about chronology. It was one of a good many things I learned almost without knowing it; it would be there when I needed it.

One Writer’s Beginnings recounts Welty’s early years as the daughter of a prominent Jackson insurance executive and a mother so devoted to reading that she once risked her life to save her set of Dickens novels from a house fire.

Welty’s childhood seemed ideal for an aspiring writer, but she initially struggled to make her mark. After a college career that took her to Mississippi State College for Women, the University of Wisconsin at Madison, and Columbia University, Welty returned to Jackson in 1931 and found slim job prospects. She worked in radio and newspapering before signing on as a publicity agent for the Works Progress Administration, which required her to travel the back roads of rural Mississippi, taking pictures and writing press releases. Her trips connected her with the country folk who would soon shape her short stories and novels, and also allowed her to cultivate a deep passion for photography.

Welty took photography seriously, and even if she had never published a word of prose, her pictures alone would probably have secured her a legacy as a gifted documentarian of the Great Depression. Her photographs have been collected in several beautiful books, including One Time, Once Place; Eudora Welty: Photographs; and Eudora Welty as Photographer. In hiring Welty, “the Works Progress Administration was making a gift of the utmost importance to American letters,” her friend and fellow writer William Maxwell once observed. “It obliged her to go where she would not otherwise have gone and see people and places she might not ever have seen. A writer’s material derives nearly always from experience. Because of this job she came to know the state of Mississippi by heart and could never come to the end of what she might want to write about.”

Because of the years in which she was most active behind the camera, Welty invites obvious comparison with Walker Evans, whose Depression-era photographs largely defined the period for subsequent generations. Walker’s pictures often seem sharply rhetorical, as when he captures poverty-stricken families in formal portrait poses to offer a seemingly ironic comment on the distance between the top and bottom rungs of the economic ladder. But Welty, by contrast, seems uninterested in using her subjects as symbols. She appears to see the people in her pictures as objects of affection, not abstract political points.

In One Writer’s Beginnings, Welty notes that her skills of observation began by watching her parents, suggesting that the practice of her art began—and endured—as a gesture of love. Even when the characters in her stories are flawed, she seems to want the best for them, one notable exception being “Where Is the Voice Coming From?,” a short story told from the perspective of a bigot who murders a civil rights activist. Welty wrote it at white-hot speed after the slaying of real-life civil rights hero Medgar Evers in Mississippi, and she admitted, perhaps correctly, that the story wasn’t one of her best. “I’m not sure that this story was brought off,” Welty conceded, “and I don’t believe that my anger showed me anything about human character that my sympathy and rapport never had.”

Welty’s philosophy of both literary and visual art seems pretty clear in “A Still Moment,” a short story in which bird artist John James Audubon experiences a brief interlude of transcendence upon spotting a white heron, which he then shoots for his collection. What Welty seems to say, without quite saying so, is that the best pictures and stories cannot simply reduce the creatures within their spell to specimens. True engagement requires a durable sympathy with the world.

That idea also rests at the heart of “Keela, the Outcast Indian Maiden,” in which a handicapped black man is kidnapped and forced to work in a sideshow in the guise of a vicious Native American. He gains his liberation only after a spectator looks past what he’s been told and sees the kidnapping victim as he really is.

The story, included in Welty’s first collection, A Curtain of Green, in 1941, was notable at its time for its sympathetic portrayal of an African-American character. That sympathy is also evident in “A Worn Path,” in which an aging black woman endures hardship and indignity to fulfill a noble mission of mercy. Welty’s generous view of African Americans, which was also obvious in her photographs, was a revolutionary position for a white writer in the Jim Crow South.

“A Still Moment,” Welty’s Audubon story, was unusual because it dealt with characters in the distant past. Most of Welty’s fiction featured characters inspired by her contemporary fellow Mississippians. One of her most widely anthologized stories, “Why I Live at the P.O.,” unfolds through the digressive voice of Sister, a small-town postmistress who explains, in hilarious detail, how she became estranged from her colorful family. The story, which predates comedian Carol Burnett’s Eunice character in its depiction of a Deep South heroine who’s both farcical and tragic, has been a fixture of The Norton Anthology of American Literature, where I first encountered it as a college freshman.

My professor, who was prone to solemn analysis of philosophical themes and literary techniques, threw up his hands after our class reading of “Why I Live at the P.O.” and encouraged us to simply enjoy it.

One can find numerous topics for scholarly reflection in “Why I Live at the P.O.”—and in any other Welty story, for that matter—but my professor’s advice is a nice reminder that beyond the moral and aesthetic instruction contained within Welty’s fiction, she was, in essence, a great giver of pleasure.

Her prose is a joy to read, especially so when she draws upon the talent she honed as a photographer and uses words, rather than film, to make pictures on a page.

One can open to a random page of any of her stories and find little gems of verbal portraiture shimmering back. Here’s how she opens “The Whistle”:

Night fell. The darkness was thin, like some sleazy dress that had been worn and worn for many winters and always lets the cold through to the bones. Then the moon rose. A farm lay quite visible, like a white stone in water, among the stretches of deep woods in their colorless dead leaf. By a closer and more searching eye than the moon’s, everything belonging to the Mortons might have been seen—even to the tiny tomato plants in their neat rows closest to the house, gray and featherlike, appalling in their exposed fragility.

Like Virginia Woolf, a writer she dearly admired, Welty used prose as vividly as paint to make images so tangible that the reader can feel his hand running across their surface. And like Woolf, Welty enriched her craft as a writer of fiction with a complementary career as a gifted literary critic.

In 1944, as Welty was coming into her own as a fiction writer, New York Times Book Review editor Van Gelder asked her to spend a summer in his office as an in-house reviewer. Gelder had a habit of recruiting talents from beyond the ranks of journalism for such apprenticeships; he had once put a psychiatrist in the job that he eventually gave to Welty.

Welty proved so stellar as a reviewer that long after that eventful summer was over and she had returned to Jackson, her association with the New York Times Book Review continued. Welty’s criticism for the Times and other publications, collected in The Eye of The Story and A Writer’s Eye, yields valuable insights about Welty’s own literary models.

Besides Woolf, Welty also greatly admired Chekhov, Faulkner, V. S. Pritchett, and Jane Austen. In her landmark essay, “The Radiance of Jane Austen,” Welty outlined the reasons for Austen’s brilliance, including her genius at dialogue and her deftness at displaying a universe of thought and feeling within a small compass of geography: “Her world, small in size but drawn exactly to scale, may of course easily be regarded as a larger world seen at a judicious distance—it would be the exact distance at which all haze evaporates, full clarity prevails, and true perspective appears.”

In writing that passage about Austen, Welty seemed to explain why she herself was content staying in Jackson. Like Austen, who had found more than enough material in a small patch of England, Welty also felt creatively sustained by the region of her birth. “I chose to live at home to do my writing in a familiar world and have never regretted it,” she once said.

But even as she continued to make a home in the house where she had spent most of her childhood, Welty was deeply connected to the wider world. She eagerly followed the news, maintained close friendships with other writers, was on a first-name basis with several national journalists, including Jim Lehrer and Roger Mudd, and was often recruited to lecture.

Welty gave inspired public readings of her stories—performances that reminded listeners how much her art was grounded in the grand oral tradition of the South.

“Colleges keep inviting me because I’m so well behaved,” Welty once remarked in explaining her popularity at the podium. “I’m always on time, and I don’t get drunk or hole up in a hotel with my lover.”

That sly humor and modesty were trademark Welty, and I was reminded of her self-effacement during my visit with her, when I asked her how she managed the demands of fame. She was softly explaining to me that she had no fame to speak of when, as if answering a stage cue, a stranger knocked on the door and interrupted our interview. He was a literary pilgrim from Birmingham, Alabama, who had come seeking an audience—one of many, I gathered, who routinely showed up at Welty’s doorstep. Welty had her caretaker gently turn him away, but the visitor’s presence suggested that Welty hadn’t escaped the world by living in Jackson; the world was only too eager to come to her.

Over her lifetime, Welty accumulated many national and international honors. Although recognized as a master of the short story, she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her novel, The Optimist’s Daughter. She also received eight O. Henry prizes; the Gold Medal for Fiction, given by the National Institute of Arts and Letters; the Légion d’Honneur from the French government; and NEH’s Charles Frankel Prize. In 1998, she became the first living author whose works were collected in a full-length anthology by the Library of America.

Welty never married or had children, but more than a decade after her death on July 23, 2001, her family of literary admirers continues to grow, and her influence on other writers endures. Welty’s home is now a museum, and the garden she mourned as forever lost has been lovingly restored to its former glory. The story of that horticultural restoration was recently recounted in One Writer’s Garden: Eudora Welty’s Home Place, a lavish coffee-table volume published by the University Press of Mississippi. Nobel laureate Alice Munro of Canada has recalled reading Welty’s work in Vancouver and being forever changed by Welty’s artistry. Lee Smith, one of today’s most accomplished Southern novelists, remembers seeing Welty read her work and becoming transfixed. The experience sharpened Smith’s desire to pursue her own work.

And novelist and short story writer Greg Johnson remembers coming to Welty’s writing reluctantly, believing she wasn’t experimental enough to warrant much attention, but then coming under the spell of her prose.

Welty is an easy writer to discount, Johnson observed, because her modest life and quiet manner didn’t fit the stereotype of the literary genius as a tortured artist.

“Do Important Writers,” Johnson wondered with tongue in cheek, “live quietly in the same house for more than seventy years, answering the door to literary pilgrims who have the nerve to knock, and sometimes even inviting them in for a chat?”

Welty had a ready answer for those who thought that a quiet life and a literary life were somehow incompatible. “As you have seen, I am a writer who came of a sheltered life,” she told her readers. “A sheltered life can be a daring life as well. For all serious daring starts from within.”