In the late 1990s, while writing an encyclopedia of twentieth-century American literature, I checked the competition to see how entries on authors were composed and what secondary sources were included. I knew very little of Amy Lowell (1874–1925)—not much more than her signature poem, “Patterns,” and Ezra Pound’s denunciation of her for appropriating the new, astringent poetry he called Imagism, and reformulating it as “Amygism,” a flaccid version of his effort to strip contemporary poetry of excessive rhetoric and make the image itself the poem’s organizing principle. I was also aware of T. S. Eliot’s slighting reference to Lowell as the “demon saleswoman” of modern poetry. The indictment was clear: Through her public lectures and spectacular platform performances, she had perverted the serious thrust of literary modernism, which rejected hucksterism and any diversion of high art to the precincts of popular taste and publicity. Implicit in Eliot’s dismissal is the suggestion that Amy Lowell might have been more than a little mad.

Two of the most up-to-date encyclopedia entries I consulted, both written by women, came to identical conclusions: A new biography of Amy Lowell was badly needed. Both Lowell and her place in literary history required reevaluation. This call for a new narrative coincided not only with demands by feminist scholars for a more inclusive literary canon acknowledging the achievements of women writers, but also, specifically, with new scholarly interpretations of Lowell’s life and career. As the contributors to Amy Lowell: American Modern (2004) argue, both the breadth and depth of Lowell’s work deserve recognition for precisely what led the Pound-Eliot axis to disparage her: a fundamental loyalty to her homeland, a desire to expand the audience for poetry, and a commitment to a conception of modernism that was both patriotic and provincial in the best sense of these words—the sense William Faulkner employed when speaking of his “postage stamp of native soil.”

At this point, I confess, my biographer’s blood was up. I already had a beef with the Pound-Eliot brand of modernism that Rebecca West—another of my biographical subjects—attacked. For West, as for Lowell, there was something distinctly inhumane, rigid, and ahistorical about a modernism that developed theories of impersonality, as T. S. Eliot did in “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” He attacked the Romantic idea of poetry as self-expression and insisted that the poet became entirely absorbed in his work and wrote himself out of existence, so to speak. Eliot and his legion of followers neglected to account for persons, places, and the era in which great literature came to life. In her book Six French Poets (1915), Lowell explored both the lives and literary work of her subjects, much as West did in The Strange Necessity (1928).

But what most drew me to Lowell’s biography was the irony inherent in the modernist rejection of her on extraliterary grounds. There was nothing impersonal about it. Lowell came from a powerful and wealthy New England family, and that background was enough to excite the scorn and ridicule of artists who lived hand to mouth, and even that of a high church modernist like Eliot, who worked first in a bank and then for a publisher. Lowell had an establishment: her ancestral home, Sevenels, complete with a large staff, a maroon Pierce-Arrow with a chauffeur, and the largesse to dole out to struggling poets and poetry publications. Her generosity engendered not gratitude, but gripes about her manorial sense of entitlement. She seemed a throwback to the eighteenth century. Even her habit of smoking cigars was interpreted not as an avant-garde gesture, but rather the eccentricity of a spoiled Boston Brahmin. And she was obese, with a five-foot frame carrying 250 pounds. The poet Witter Byner, one of her rivals, called her the “hippopoetess”—and the joke stuck. Even her lesbianism failed to garner any cachet among the outré modernists; she observed the conventions, always referring publicly to her lover as her companion, Mrs. Russell. And Lowell never made an effort to meet Gertrude Stein, despite both women’s obvious affinities with the French. Stein got points for leaving America—a sign of her internationalist modernism—but Lowell ventured out mainly on her native ground and mainly to give lectures, many of them sponsored by women’s clubs, then considered the realm of amateurs and dilettantes by male modernists. I knew otherwise, having followed Rebecca West into those clubs and watched as she reacted to women who had read and reflected on her work. That some of these clubs included fools and what might be called literary tourists is almost beside the point; the avant-garde behaved no better.

So why read Amy Lowell? And, if we read her work, what should be read? How is she an American modern whose stock should be reevaluated upward? For my part, I favor her lyrics such as “Absence,” “Carrefour,” and “Venus Transiens”—not as the only worthy examples of her work, but as exemplars of her highest achievement. To assess her significance, I have to call on biography to reveal the passionate woman and poet, whom D. H. Lawrence—alone among his fellow male modernists—recognized as an equal, even if he could not always approve of her subjects or her methods.

Lawrence’s letters to Lowell have been published and, among other things, they reveal that Lawrence thought Lowell was at her creative best when she was drawing on her own American identity, rather than on historical epics and French, Japanese, and Chinese poetry. I think he failed to see that in those works, too, she was assimilating the foreign so as to make it familiarly American. To put it another way, Lowell wanted Americans to treasure their experience, to understand that it is suffused with the lives and history of other peoples.

To this missionary desire, Lowell added her own eroticism, born of a sensual nature that her critics and biographers have refused to acknowledge on its own terms. Although her first biographer, the hostile Clement Wood, exiled her as a “singer of Lesbos,” her subsequent biographers and critics deprived Lowell of even that island of love—either ignoring her sexuality altogether, like her authorized biographer, S. Foster Damon, or suggesting, like Glenn Ruilhey and Richard Benvenuto, that Lowell’s love poetry reflects an unconsummated pretend romance, not a physical union with her beloved Ada Russell (1863–1952), who lived with the poet and was a part of every intimate moment in her life. These male critics and biographers could not envision a physical relationship between the corpulent Lowell and Russell, a decade older and middle aged when the women began living together. Only Jean Gould, in her 1975 biography, gingerly introduced the lesbian nature of Lowell’s love poetry—but without quite comprehending the central role Lowell’s sexuality played in her work.

Until now, it has been supposed by Gould and subsequent generations of feminist critics that Lowell had no more than one great love. In fact, before Russell, there was Elizabeth Seccombe, whose very existence is unrecorded in Lowell’s massive Houghton Library archive, and whose crucial role in Lowell’s life has only recently been discovered in the papers of Robert Grosvenor Valentine. Valentine, who became President Taft’s commissioner of Indian affairs, at one time played a pivotal role in a small group of amateur poets who sought in one another the approval and criticism that might one day result in superior work. Only Lowell emerged from this group, grieving over her breakup with Seccombe, and vouchsafing her heartache in a letter to Valentine and then in her first published book of poetry, A Dome of Many-Coloured Glass (1912), which appeared three years after the breakup with Seccombe. Lowell’s earliest published poems express not only dread that she cannot fulfill her dreams of poetic greatness, but also fear she will never be able to share that achievement with the one she loves. And yet, previous biographers never considered such poems confessional.

Why Lowell and Seccombe parted is not clear, although the latter states in one of her letters that Lowell initiated their divorce. The word seems right, because these two women traveled everywhere together, just as Lowell would later do with Russell. For whatever reason, Seccombe—dependent on Lowell’s support and perhaps not quite strong enough to stand up to her partner’s demanding temperament—could not function as Lowell’s muse, and could not be the lover-ideal the poet so desperately wanted.

To think of Lowell as some kind of repressed, tormented spinster, unable to bear the sight of her own body, living out her fantasies in words rather than in deeds—as C. David Heymann does in his biography of the Lowells (James Russell, Amy, and Robert)—is to wallow in a vulgar Freudianism that treats Lowell’s poetry as an exercise undertaken as compensation for a loveless life. To be sure, Lowell had moments when she did not want to be reminded of her stout figure, when she draped mirrors in cloth, and even called her condition a “disease.” But more often, she took her size in stride and was perfectly capable of joking about it with an ease that suggests anything but embarrassment. To see her performances in public readings as merely enactments of a courting ritual with the reading public is to miss the joy Lowell expressed about her own sensuality.

Some of her poems are quite literal, yet biographers could not see what Lowell wrote in “Absence,” where loneliness is visualized as an empty cup and then as the poet’s heart.

The cup of my heart is still,

And cold, and empty,

When you come, it brims

Red and trembling with blood,

Heart’s blood for your drinking;

To fill your mouth with love

And the bitter-sweet taste of a soul.

Lowell once advised D. H. Lawrence that he did not have to use explicit words when considering sexual congress. Lady Chatterley’s Lover, of course, was later the focus of a trial in which Rebecca West and other notable literary figures defended Lawrence against the charge of obscenity and won the argument that his work should be openly published without censorship. Lowell insisted to Lawrence that there were ways of conveying sensuality that would not put off the larger audience she wanted for his work. She was speaking from experience.

But “Absence” is about more than sex. It can be read as a work about how love fills the void in one’s life, nourishing the self. Lowell describes the “cup of my heart” that fills with love, just as the body responds to a lover’s touch. But the male critics who read these poems understood them only as metaphorical. They could not, as Emily Dickinson put it in a poem about a dying person, “see to see.” Lowell’s sensuality was not visible to them because, it seems, they did not imagine that she was describing her own experience.

It is not only Lowell’s own experience that is at stake here. On the contrary, she wanted to reveal the eroticism of other literatures, which began to shape her own sensuality from the first day that her brother Percival brought home the Oriental art he had acquired on his trips abroad. Her Chinese- and Japanese-inspired poems were acclaimed by no one, with the honorable exception of the poet Kenneth Rexroth, who recognized Lowell as a master. Instead, generations of critics remain besotted with Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro,” as if this Imagist poem with its startling metaphor is the end-all of modernism:

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

petals on a wet, black bough.

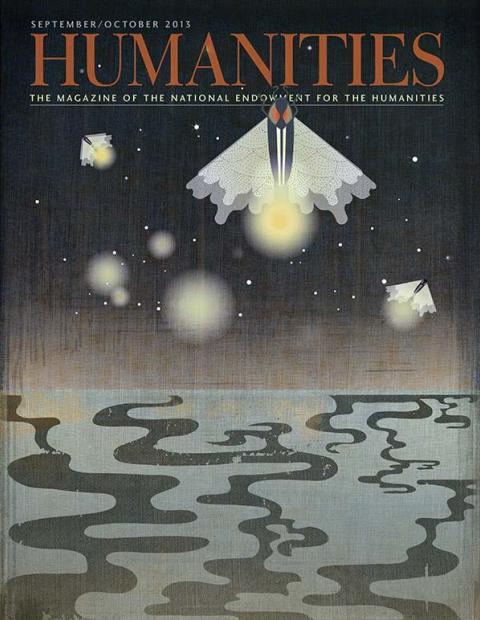

Lowell thought there was another way—less compressed than Pound’s, but no less suggestive. A case in point is “To a Husband,” published first in the March 1917 issue of Poetry, and then reprinted in Lowell’s exquisite collection Pictures of the Floating World:

Brighter than fireflies upon the Uji River

Are your words in the dark, Beloved.

The poem is simplicity itself. What else is there to say? Compared with the cold Pound, intent on the shapes and silhouettes of his perceptions, chiseling a scene into the etching of a poem, Lowell revels in the electric atmosphere of love, in the sparks, no less, that occur in the marriage of lovers—a subject she came to know well during her passionate decade with Ada Russell. And what about those words in the dark, the power of words to ignite love? This kind of love escalates, as Lowell’s love for Russell does in poem after poem, so that even the exquisite sight of those fireflies on the Uji River cannot outdo what the husband says. The fireflies are evanescent, appearing and disappearing, but the light of the wife’s love is more enduringly present. What the husband says is not revealed, but in the absence of his actual words, we project our own longing for the love the poem expresses. The reciprocal nature of love—the give and take of it—suffuses this brief poem.

The Uji River, near Kyoto, can be accessed via walking bridges that make the water that much nearer, intensifying the fluid medium of love that is also expressed in the rushing rapids—not part of the poem, but part of the world out of which the poem emerges. Uji, the site of ancient temples, is also the setting for the final chapters of The Tale of Genji (c. 1000), a novel fraught with all sorts of romantic associations and conflicts that bring couples to the site of passion, reverie, and prayer.

Mentioning the Uji River is Lowell’s way of bringing history and culture to bear on the personal, intimate moment. She lamented that in America people too often neglected to savor their role in the universe, or to appreciate how their feelings arose out of nature itself. Lowell wrote to Sara Teasdale on August 13, 1917, “It has been hot, but we have had a perfect show of fire-flies over the garden every evening. . . . It was the kind of thing they speak about in Japanese books as happening over the Uji river in Japan. If we lived in that country people would have come out to see it.” This desire to connect the human with the natural is, of course, a staple of romanticism, but one that had become outworn by Amy Lowell’s day. She sought to invigorate the nexus in her spare lines.

Lowell often said there is more to her poetry than might be apparent. She was dismissed as a poet of glittering surfaces and pyrotechnical imagery. Her best work certainly does have a sheen, but that glow belies the volumes of feeling on which that showy superstructure is built. As with “To a Husband,” many of her best poems grow in resonance and profundity when the full context of her images is probed. Even as Lowell guided the last of three Imagist anthologies to press at the end of World War I, the Imagist movement was subsiding. Nevertheless, she continued to practice many of the movement’s principles—especially the exhortation to concentrate on “direct treatment of the thing,” which in practice meant forsaking the florid language of the Victorian age and the sentimental expressions of the genteel tradition. That such poetry was austere did not mean it was without feeling; on the contrary, as Lowell understood Imagism, it aimed to present maximum feeling in the fewest lines possible.

Of course, Lowell failed more often than she succeeded, but, as her staunch supporter John Livingston Lowes argued, she created great poems sufficient to fill a substantial book, poems including “Patterns,” “Lilacs,” “Venus Transiens,” “Madonna of the Evening Flowers,” “The Taxi,” “Absence,” “The Onlooker,” and at least a dozen more. That her biographers have not recognized this achievement—and, in Horace Gregory’s case, even claimed Lowell was no poet at all—is one of the infamies of American biography and literature.