In 1813, a young Thaddeus Stevens was attending a small college in Vermont. This was well before the time when good fences made good neighbors. Free-roaming cows often strayed onto campus. Manure piled up. Odors lingered. Resentment among students festered. One spring day, Stevens and a friend “borrowed” an ax from another student’s room and killed one of the cows, and then slipped the bloody weapon back into the unsuspecting classmate’s room.

When the farmer complained, the school refused to let the wrongly accused man graduate. Stevens, unable to stomach this injustice, contacted the farmer on his own, fessed up, and made arrangements to pay damages. The farmer withdrew his complaint, and, within a few years, Stevens paid the farmer back. In gratitude, the farmer sent Stevens a hogshead of cider.

The anecdote demonstrates early on in his life Stevens’s basic character—his rashness, his inconsistencies, his convictions, and his tenacity.

We know Thaddeus Stevens as an ardent abolitionist who championed the rights of blacks for decades—up to, during, and after the Civil War. With other Radical Republicans, he agitated for emancipation, black fighting units, and black suffrage. After the war, he favored dividing up Southern plantations among the freed slaves, embracing William Tecumseh Sherman’s “forty acres and a mule.” Throughout his career, he championed reforms in education and finance, but what seems to us today a minor cause—a growing hostility to freemasonry—was the spark that ignited his early political career.

Thaddeus, the second of four children, saw the light of day in a village in northern Vermont in 1792 and was named to honor Polish patriot Thaddeus Kościuszko. He was born with a clubfoot, and when he was twelve his father abandoned the family. Thad’s mother held things together while he and his siblings were growing up, and she insisted her sons all get a decent education.

Just as Stevens was graduating from Dartmouth, he heard of a teaching opportunity in York, Pennsylvania. He traveled to the state’s south-central county bordering the Mason-Dixon Line and took up the post, teaching Latin, Greek, English, math, science, and moral philosophy. At night, he studied law. He soon passed the bar exam and set up a practice in Adams County in the town of Gettysburg.

Stevens became known as a formidable opponent in court. Defending a Gettysburg man who was accused of killing a fellow worker with a scythe, Stevens skillfully employed an insanity defense. His client was found guilty, but Stevens’s creative and vigorous advocacy was widely admired and his practice grew. In another early case, he represented a slave owner against a runaway slave, and won. Shortly afterward, however, he began representing runaway slaves and never changed sides on the issue again.

Future president James Buchanan worked with Stevens on a case being tried in York. During a break, Buchanan attempted to persuade the rising attorney to get involved in politics—on the side of the Jacksonian Democrats. Stevens declined, as he was still in search of the political party that best matched his beliefs.

An entrepreneur as well as a lawyer, Stevens founded an ironworks called Caledonia that he operated until 1863. The forge was destroyed by Confederate General Jubal Early on the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg. The decision to destroy the forge was entirely Early’s. He justified the action by citing Stevens’s hostility to slave owners’ property in the South. Stevens was always highly regarded, though, by employees at Caledonia. When the forge was destroyed, he made sure his workers were not immediately cut off without income.

Stevens vehemently opposed secret societies, especially the Masons. During the colonial period and the Revolution, the Masons had found many adherents among the Founders. Freemasonry is a nondogmatic, ritualistic fraternal order whose members recognize a supreme being and are devoted to charitable work. But Stevens and others regarded the Masons, with their oaths and penalties, as elitist and a peril to democracy.

In the late 1820s, anti-Masonic feeling was on the rise, putting many local and national leaders who were active Masons on the defensive. In a letter dated January 11, 1835, to John Quincy Adams, Stevens sought the former president’s views, which he felt might “materially aid the cause of pure Antimasonry.” The Whigs in Pennsylvania found it easy to come together in opposition to President Andrew Jackson—a Mason—and his attack on the U.S. Bank. Stevens favored rechartering the Bank, while Jackson opposed it. Stevens and the Whigs believed firmly in sound money and high tariffs. Jacksonian democracy became their common enemy.

Stevens the lawyer took up more high-profile cases, at least once placing himself in the middle of a convoluted feud between the local anti-Masonic newspaper (which he would later come to own) and the local pro-Masonic newspaper. In 1833, he was elected to the state legislature as the representative from Adams County. In a speech in the State House in March 1834, he railed against Governor George Wolf and President Andrew Jackson for their policies regarding the Bank of the United States—policies which, Stevens felt, left Pennsylvania in debt and without credit: “A spendthrift Administration, regardless of every thing but the wants of their needy favorites, have squandered her treasure, deranged her finances, and loaded her people with burthens, . . . the hungry cormorants of office and plunder will hardly be sated!”

And there was more. “It makes the soul of the patriot die within him,” he continued, “to see the heart’s blood of this great state, sucked by the creeping vampyres, and her bones crushed by the Hyenas and Jackalls of party!” Then, with no intended irony regarding the bondage of African Americans, he observed, “Pennsylvania is so patient under tyranny, that slavery seems well to become her.”

Drawing near the peroration, Stevens said, “When Rome was the sport of a despot, she had all the forms of freedom. Her Senate—her Tribunes and Aediles. But her Senators were the tools, and her Tribunes and Aediles the slaves of Caesar.”

This early hyperbolic speech was seasoned with what became characteristic Stevens rhetoric. His tendency to loosely refer to any harsh reality in the lives of contemporary whites as slavery, however, dissipated as he reacted to other currents in the national debate.

When legislators from Virginia, Kentucky, and Mississippi insisted that abolitionists in other states refrain from criticizing the “peculiar institution,” he answered them. “Every citizen of the non-slave holding states,” he declared in May 1836, “has a right freely to think and publish his thoughts on any subject of national or state policy. Nor can he be compelled to confine his remarks to such subjects as affect only the state in which he resides.” At the Pennsylvania Convention of 1837, he was the only member to vote against amendments that would exclude blacks from voting. He said he had not expected to hear it maintained “that GOD did not, out of one clay, create all mankind; nor to hear the Holy Scriptures cited as an apology and license for oppression.”

Stevens’s oral remarks and written correspondence have been gathered in The Selected Papers of Thaddeus Stevens, edited by Beverly Wilson Palmer and Holly Byers Ochoa and published by the University of Pittsburgh Press. “The Old Commoner,” as he came to be known, had nearly indecipherable handwriting and destroyed many of his letters. The natural question is, Was he hiding something? Palmer thinks not, speculating that he merely discarded whatever he thought was incidental. But his remaining letters, plus his arguments before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, his speeches throughout the commonwealth, and, later, those in Congress, limn the arc of a remarkable career—one in which he agitated ceaselessly for educational and financial reform, an end to slavery, and universal black suffrage.

Stevens’s legal work gained him a good income, and he was at one time Gettysburg’s largest property holder. From 1821 to 1830, according to biographer Alphonse Miller, he participated in every case that went to the State Supreme Court from Adams County. As a state legislator, he gained attention while working with his sometime foe Governor Wolf to rescue an education law for free schools. On April 11, 1835, in the Pennsylvania House, Stevens eloquently expressed his hope that the “blessing of education . . . shall be carried home to the poorest child of the poorest inhabitant of the meanest hut of your mountains, so that even he may be prepared to act well his part in this land of freemen.”

By the early 1840s, Stevens’s fortunes as an anti-Mason Whig and a state legislator were turning against him. The undistinguished finale came during the Buckshot War—an unsettled few weeks following statewide elections marked by alleged corruption. At issue were lost election tallies in the Northern Liberties section of Philadelphia. When the new legislative session got underway, angry mobs with bowie knives and other weapons forced Stevens to leap from a window of the Capitol.

Stevens was now looking to move on and increase his law business, mainly so he could meet mounting debts incurred at Caledonia. He chose Lancaster—a Democratic city with a large Pennsylvania-German population, surrounded by farmland cultivated by thrifty farmers—a fair share of whom were wealthy and tended to support the Whigs.

Not long after he arrived in August 1842, Stevens purchased a townhouse just south of the central square. His new digs served as both residence and office. Lydia Hamilton Smith, a woman of color and a widow with two children, did the housekeeping. At first she lived in a separate house in the rear, but after a time she moved into the main residence with her children. If there was an intimate side to her and Stevens’s relationship, it never came out in any letters or documents, but biographer Fawn Brodie found much circumstantial evidence implying otherwise. Stevens always treated Mrs. Smith as a confidante and coequal. When there were events and gatherings in Stevens’s home, Mrs. Smith was the hostess. Stevens’s niece in Indianapolis would sometimes implore the two of them to visit and would tell her uncle to “give her a great deal of love for me.” Formal invitations to soirées at the Stevens addresses in both Lancaster and Washington were few, but the ones that were sent out were always in Mrs. Smith’s hand. Late in life, Stevens denied any intimacy with Mrs. Smith, but in many ways they had lived as a couple.

In Lancaster, Stevens’s practice grew steadily, and young men sought him out to study law in his offices, while his interest in politics and personal causes diminished not at all. He hired spies to keep an eye on slave-catchers in town, and his residence became a station on the Underground Railroad—a fact acknowledged in April 2011 by the National Park Service. The Christiana riot trial, in which Stevens helped gain acquittal for two Quakers who stood by during a melee, refusing to help slave-catchers, won him few friends in nearby Lancaster City. Meanwhile, he instructed his personal physician to send him the bill for any “deformed or disabled” boys he treated.

Still no mainstream Whig, Stevens continued to attract political foes of nearly every stripe—Silver Grey or Cotton Whigs and other northerners and proslavery Democrats such as the Hunkers and the doughfaces and, eventually, the Copperheads, who were unwilling to oppose slavery. Stevens crossed swords with any proponent of popular sovereignty who would have the new territories decide the slavery question for themselves.

Stevens corresponded with another young lawyer interested in antislavery issues: Abraham Lincoln who, then a U.S. congressman, had met Stevens at the Philadelphia Whig convention. “You may possibly remember seeing me at the Philadelphia Convention—introduced to you as the lone Whig star of Illinois,” wrote Lincoln, almost deferentially, in September 1848. Thus began one of the few letters between the two future Republicans who would lead the country through civil war and emancipation. Even here the contrasts stand out, with Lincoln ever halting and cautiously waiting for public approval before committing to action, while the radical Stevens would always be far in advance of popular opinion. On this day, however, Lincoln was merely gathering information from the savvy Lancastrian: “I desire the undisguised opinion of some experienced person and sagacious Pennsylvania politician, as to how the vote of that state, for governor, and president is likely to go.”

Stevens could, indeed, be sagacious but he could also be erratic. In 1859, he supported the presidential nomination of Judge John McLean over Lincoln. McLean had been appointed a justice of the Supreme Court in 1830 by Andrew Jackson, and Stevens got to know McLean when the two lived briefly in the same bachelors’ quarters. Stevens had always admired McLean’s combative stance toward Jackson. Today, of course, his decision to support the conservative McLean over Lincoln looks, as Fawn Brodie put it, “absurd.”

Stevens was better known for his rapier wit than for his abilities as a kingmaker. His barbs often found their mark during spontaneous repartee, rather than in letters. One day, as he was following a narrow path in Lancaster, he encountered one of his enemies, who was coming from the other direction and refused to give way. The man shouted, “I never get out of the way for a skunk.” Stevens stood aside and replied, “I always do.”

Years later, when Lincoln discussed cabinet positions with Stevens, the president inquired about one of Stevens’s adversaries from Pennsylvania, Simon Cameron. Stevens implied that Cameron could be less than scrupulous in financial matters. “You don’t mean that Cameron would steal?” asked Lincoln. “No,” came Stevens’s near-instant reply, “I don’t think he would steal a red hot stove.”

Elected to Congress, Stevens wasted little time in stating his opposition to slavery. On February 20, 1850, he reiterated his abhorrence of slavery but reaffirmed that he would “stand by all the compromises of the Constitution, and carry them into faithful effect.” He continued—now using the term “slaves” consciously and ironically—by sarcastically congratulating the South on, in his view, its successes in intimidation: “You have more than once frightened the tame North from its propriety, and found ‘dough-faces’ enough to be your tools. And when you lacked a given number, I take no pride in saying, you were sure to find them in old Pennsylvania, who, in former years, has ranked a portion of her delegation among your most submissive slaves.” The Lancaster Intelligencer commented that it was “a violent tirade of abuse against the Southern people and their ‘peculiar institution,’” concluding that Stevens’s philippic would only “inflame their passions and excite still further prejudices against the North.”

The Commoner’s enemies in the South were certainly delighted that Stevens’s foray in Congress was for just one term. On the House floor in June 1850, Stevens said that, according to his interpretation of the Constitution, “any slave escaping or being taken into New Mexico or California, would be instantly free.” And he followed that up with what was anathema for Southerners and many northern Democrats sympathetic to the South, that “Congress alone has the exclusive power to legislate for the territories.”

In Lancaster County, support among Whigs for nominating Stevens to another term dwindled, and he was not selected by them to run again. Returning to the Red Rose City, Stevens concentrated on his law and business interests, but politics was never far from his mind. He organized nativists and Know-Nothings to help defeat Whig candidates. At a rally in Lancaster in October for Republican presidential candidate John Frémont, Stevens skewered the Democratic candidate, his fellow townsman: “There is a wrong impression about one of the candidates. There is no such person running as James Buchanan. He is dead of lockjaw. Nothing remains but a platform and a bloated mass of political putridity.” The intemperate tone was faithful to many speeches by many politicians of the day, on the floor of Congress and elsewhere, but Stevens could go further, injecting a strong whiff of brimstone into his remarks.

Eighteen fifty-seven was another busy year for Stevens in his law office, and he spent the time exercising his profession, which included perfecting his sarcastic asides during cross-examinations. In August, however, he was nominated again for Congress, now as a Republican. He reiterated his unwavering stance against slavery and his support for tariffs, claiming the state’s workshops were idle due to the effects of free trade. The Intelligencer’s reaction: “He has always been powerful for mischief, but powerless for good, and has destroyed every party and every cause where he has been permitted to take the lead.”

Back in Congress in 1859, Stevens was, in spite of the Intelligencer’s misgivings, permitted to take the lead, and at a most propitious moment. John Brown had been hanged on the Friday before for his unsuccessful raid on the muntions depot in Harpers Ferry. On Monday, Stevens was engaged in the rapid-fire exchange of insults and general acrimony between Southern representatives and House Republicans, the Southerners blaming the Radical Republicans for Harpers Ferry. Stevens so infuriated William Barksdale of Mississippi that Barksdale threatened Stevens with a bowie knife. Shaken by the suggestion of violence, Stevens, nevertheless, shrugged it off as “a mere momentary breeze.”

Later on in that session, Stevens showed that he would not be brushed off. “Now, sir,” began the Commoner, addressing the clerk and baiting the Democratic party, “which means, of course, the Democrats of the South; the others are mere parasites.” There was laughter at the remark and an objection from Clement Vallandigham of Ohio, one of John Brown’s interrogators after the events at Harpers Ferry and one of Stevens’s most combative enemies, who found Stevens’s language “untrue and offensive.” Stevens withdrew the word “parasites” in order to “simply use the word satellite—revolving, of course, around the larger body, as according to the laws of gravitation they must—and that is not offensive.” Again, there was laughter.

In the special thirty-seventh session of Congress, though, Stevens, now a Radical Republican both in name and in deed, did much more than display his wit; he became a war leader. He whisked many bills through the chamber to finance the war, including one revising the tariff in order to increase revenue. “He knew how to make deals,” Palmer said in a telephone interview for this article, “and he was crafty.” Stevens often disagreed sharply with Lincoln on conduct of the war itself, especially with regards to blockading Southern ports.

The government, Stevens reasoned, had put itself in a “false position by attempting to close the ports, and calling it a blockade. Nations do not, correctly speaking, blockade their own ports. That term applied only to operations against foreign nations. When a blockade is declared, it is a quasi admission of the independent existence of the people blockaded.” Stevens went to the White House to tell Lincoln he should have closed the ports instead. Lincoln acknowledged the error, allowing he knew little about international law.

In Stevens’s last eight years, starting in 1859, his victories in Congress were roughly equal in number to his losses, but the quality of his victories could be considered great. He passed a bill to authorize black soldiers and a bill for the Thirteenth Amendment, outlawing slavery, which represented the culmination of much of his life’s work. Passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments, establishing equal protection before the law and the right of all males to vote, were major victories for Stevens and the Republicans, but during this same period Stevens saw a large number of defeats, such as the failed attempt to impeach Andrew Johnson.

On the House floor on February 2, 1863, the Commoner offered a near perfect summation of his own principles as he answered a critic of authorizing black soldiers. “The gentleman from Kentucky,” began Stevens, “objects to their employment lest it should lead to the freedom of the blacks. . . . That patriotism that is wholly absorbed by one’s own country is narrow and selfish. That philanthropy which embraces only one’s own race, and leaves the other numerous races of mankind to bondage and to misery, is cruel and detestable.” But it was upon passage in the House of the bill authorizing the Thirteenth Amendment that Stevens uttered the words he’s best remembered for: “I will be satisfied if my epitaph shall be written thus, ‘Here lies one who never rose to any eminence, and who only courted the low ambition to have it said that he had striven to ameliorate the condition of the poor, the lowly, the downtrodden of every race and language and color.’”

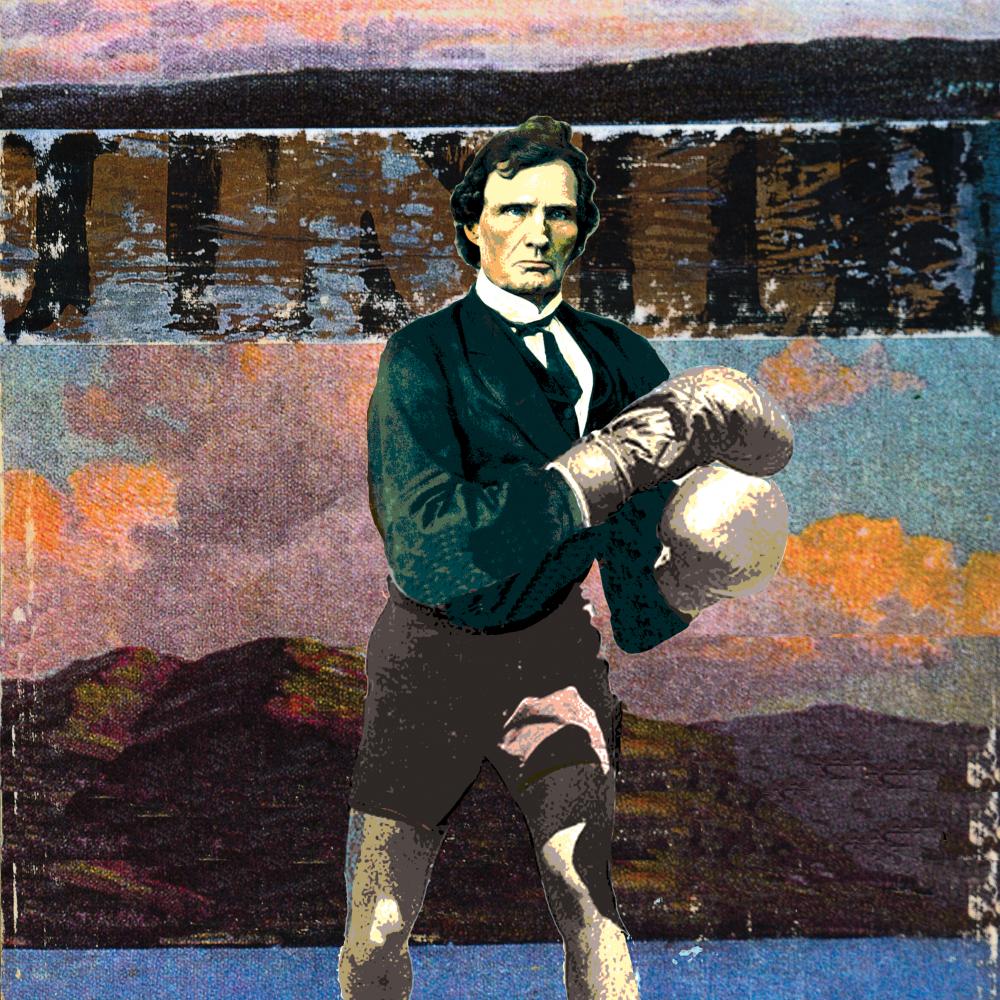

In his final years, he remained as bellicose as ever, even as his health declined and he grew so weak that he had to be carried into the House chamber in a chair. His speeches in those days often started in a whisper as members formed a tight circle around him to hear, but then grew louder, as he gathered strength, until everyone could finally hear him. When he passed away in his home on South B Street, near the Capitol, in August 1868, there were many words of admiration. Even the Intelligencer found something nice to say, and Simon Cameron remarked that “from the time of his entry into public life no man assailed him without danger or conquered him without scars.” It can be the stuff of tragedy when statesmen’s words and deeds are no kin together, but the fighting words of Stevens were more often than not close cousins of his radical deeds, especially on issues of equality. If silence reigned for a few moments in Washington the day his body, guarded by black Zouaves, lay in state beneath the Capitol Rotunda, it was because the pugilist was finally at rest.