In late 2004, Larry Sanger, who cofounded the online encyclopedia Wikipedia in early 2001 only to leave the venture a year later, wrote that his creation suffered from a “lack of public perception of credibility.” In an article titled “Why Wikipedia Must Jettison Its Anti-Elitism,” Sanger concluded that “regardless of whether Wikipedia actually is more or less reliable than the average encyclopedia, it is not perceived as adequately reliable by many librarians, teachers, and academics.” Because anyone, knowledgeable or not, could create or contribute to Wikipedia’s articles—articles which would then be published without undergoing “traditional review processes”—the encyclopedia could never be a respected reference source. At the root of it all, Sanger observed, was one major problem: “Wikipedia lacks the habit or tradition of respect for expertise.”

The lack of respect was not incidental. Jimmy Wales, Sanger’s partner in Wikipedia’s creation, is a determined egalitarian who has said, for instance, that he doesn’t care one bit if a Wikipedia contributor happens to be “a high-school kid or a Harvard professor.” This classless philosophy has been internalized by Wikipedia’s extensive community of contributors and editors. They believe Wikipedia “works,” so to speak, precisely because it holds credentials to be insignificant and because the site’s administrators and active users so stalwartly defend its openness. Sanger, however, disagrees with their view. He writes that Wikipedia—which is now the seventh-most accessed website in the world—“can both prize and praise its most knowledgeable contributors, and permit contribution by persons with no credentials whatsoever. That, in fact, was my original conception of the project. It is sad that the project did not go in that direction.”

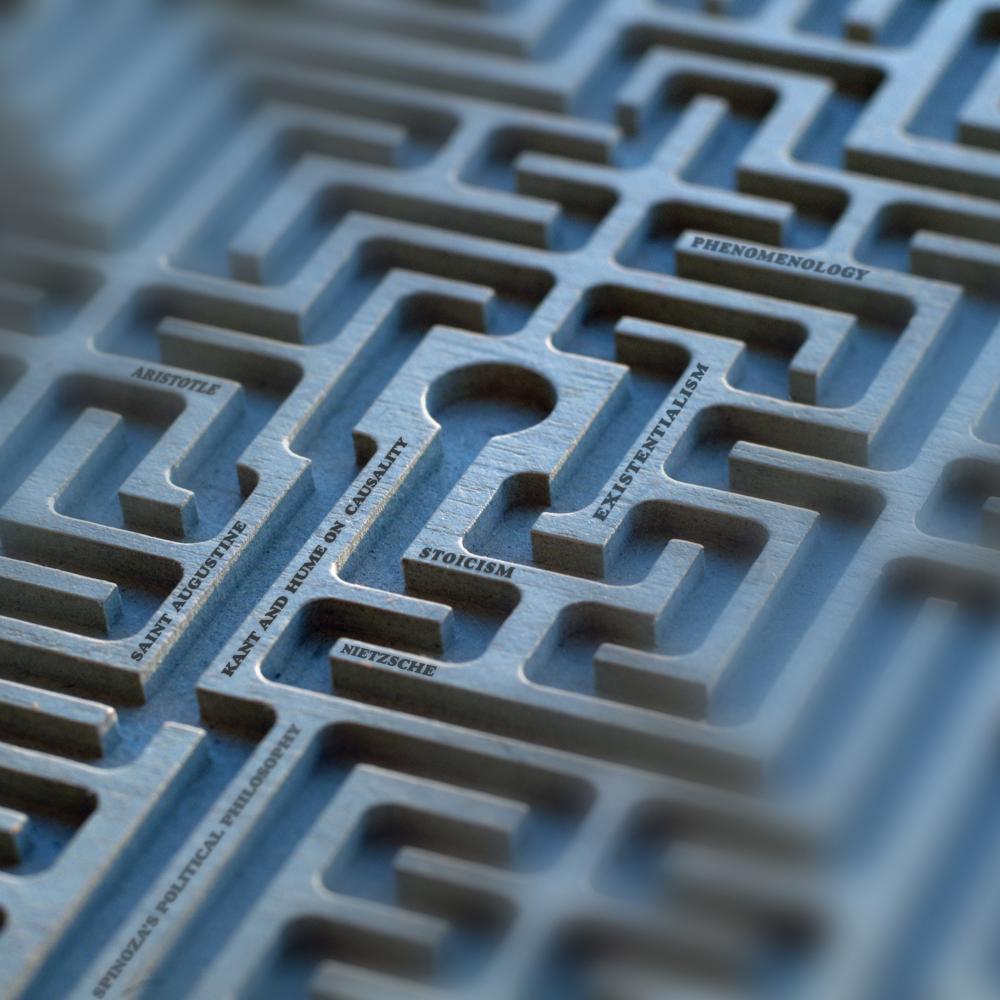

One project that did go in that direction is the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which was up and running in 1995, six years before Wikipedia’s debut, and whose entries, while written and reviewed by credentialed, named, academic experts, are also open for non-credentialed readers to offer critique and feedback. All articles, before they are made public, are reviewed by members of an editorial board composed of some 120 university-based philosophers, each of whom focuses on a particular subspecialty. These board members may approve an entry in its inceptive form, or (more commonly) suggest to the author potential revisions. Only after this process has been completed and the article in question has met with editorial board approval is the piece posted online and made publicly available. Wikipedia this is not.

The SEP’s approach seems to have worked. The resource’s credibility and accuracy are unquestioned (I, for one, could find no questioners), and it attracts an abundant audience, with between 600,000 and 700,000 accesses per week during the academic year. It is not difficult to understand why the SEP is so popular, either, for in addition to its precision it clearly fulfils a need that paper-and-glue encyclopedias cannot. The Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy was published in 1967; and it wasn’t until 1998, with the appearance of the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, that a newer, wide-ranging reference work on the subject became available. Thirty years is entirely too long to wait for an updated encyclopedia, no matter the discipline covered. Wikipedia is popular, too, of course, but for different reasons than the SEP.

Wikipedia is where one goes to quickly determine the capital of Senegal, or to recall who produced the 1971 album Gimme Dat Ding. But Sanger is right: Wikipedia is, above all, a handy resource, more distinguished for its convenience and size than its consistency. As a source of information, it remains suspect in many scholarly and intellectual circles. Also it suffers from its own generalized viewpoint. A reference to Wikipedia in a student paper or scholarly work (outside of maybe popular culture and technology subjects) risks the appearance of laziness. And for students and scholars there remains the problem of its anonymous authorship. Nor does it offer the scholar who might contribute content much of a feather for his tenure-aspiring CV. The SEP, by contrast, passes these tests.

The SEP began in 1994 when John Perry, then the director of the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University, suggested to his colleague Edward Zalta that he, Zalta, consider designing some sort of “Internet-based dictionary of philosophy” that would be publicly accessible. Zalta thought that a fine idea but wondered if a dictionary wouldn’t be too limited in scope; he saw a need for an online encyclopedia of philosophy. He also determined that the Internet would allow such an online reference work to be dynamic, not static—that the Internet could, in other words, give such a compendium its biggest advantage over bound philosophy encyclopedias: i.e., its entries could be edited as needed. The web was “just the right place to publish a reference work,” Zalta says, “because it’s a revisable medium.” As Zalta and Perry wrote in 1997, an online, dynamic encyclopedia would be “responsive to new research and advances in the field.” It wouldn’t, that is, need to wait thirty years before it could accurately reflect change. The SEP came online in 1995, with just two entries for Gottlob Frege and Turing Machines.

Zalta’s model of a “dynamic reference work” contained several innovative elements. When he began designing the SEP, for instance, he figured it would be too burdensome to have authors contact him every time they finished an article, or every time they wanted to make even minute edits to an already-completed article. Thus, he designed the SEP so that authors could upload their work online directly, to a page accessible only to editorial board members. Zalta also programmed the encyclopedia’s system to automatically alert the editorial board member in charge of reviewing a given entry the minute the author finished that entry (or finished editing an existing entry) and placed it online. The editor would then review the article, and either approve it or send the author suggestions for revisions.

An SEP author is encouraged to keep up with the articles he writes—to update them as needed and make regular revisions to reflect, say, new developments in logic. “When an author makes a change,” Zalta told me, “our software highlights just the changes so that subject editors don’t have to re-read the whole entry.” Susanna Siegel, who works in the philosophy department at Harvard University, has said that the SEP’s editorial method is as rigorous as those used by scholarly journals. “The editors are terrific,” she said. “They know who to invite to write entries . . . and their editing is superb.” New entries appear regularly. On the SEP website, a section titled “What’s New” details all the recent updates made to the encyclopedia. On October 11, for example, a brand new entry on “Africana Philosophy” written by Lucius T. Outlaw Jr., was published. Also on October 11, the entries on “Fatalism” and “Existentialism” were officially revised, and a new entry on “Miracles” appeared. There is also a “Projected Contents” page that describes what entries are on tap—some in the revision phase, others still awaiting writers.

Who uses the SEP? Stressed undergraduates cramming before exams, professors looking for a topical refresher, or “regular” people who are just interested in philosophy? Uri Nodelman, one of the SEP’s executive editors, says the encyclopedia is accessed by all three categories of users. Although the SEP, according to Nodelman, “hasn’t done much quantitatively to develop an accurate picture” of the typical person who logs on, an eight-year-old survey suggests that most of the SEP’s audience “are members of the general public.” And what are they looking up? Over the last academic year, the encyclopedia’s entry on Friedrich Nietzsche was the most accessed—followed by “John Locke,” “Kant’s Moral Philosophy,” “Game Theory,” and “Existence.” Unfortunately, the SEP cannot yet devote substantial staff time or money to tracking when entries are accessed (if, say, the encyclopedia draws more users around final-exam time), but the encyclopedia’s caretakers hope to do more of this sort of tracking in the future.

The SEP is run, rather amazingly, by a staff of just three executive editors—Zalta, Colin Allen of Indiana University, and Nodelman of Stanford—who are able to do the job because the encyclopedia was purposefully designed to streamline many of the front-end processes such as commissioning authors, assigning deadlines, and reminding authors of upcoming or past deadlines*. When, for example, a subject editor suggests an author to write a given entry, he does so through his or her SEP web interface; the principal editor is alerted to the suggestion, logs into his own web interface, and clicks a button to invite the proposed author to compose the given entry. Prospective authors have their own interface, too. When they receive an invitation from SEP, they are sent to a special web interface that contains information about the encyclopedia and their entry, instructs them to set up an account with SEP if they wish to accept, and asks them to set their own deadline for completion. The SEP system tracks all of this, sending out automatic reminder e-mails, and it also routinely prods editors and authors through every step of the process. Once an entry is published, the SEP system will automatically schedule a revision reminder in three to five years (although some entries are scheduled to be updated at least once a year, depending upon the subject matter they cover). And in order to facilitate academic citation, SEP archives its entries four times annually.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica has been publishing a print edition since the late eighteenth century. Its prospects for continuing to do so, however, or at least to do so profitably, are dim. It recently attempted to make its online material free to all. That plan didn’t work—it couldn’t support its editorial process by giving away its content—and so one year of Britannica’s online access now costs $69.95.

Wikipedia is free, of course, but why wouldn’t it be? Its editorial process isn’t rigorous or controlled, and it doesn’t value expertise. Access to the SEP, however, is also free, and that is more difficult to comprehend. How does the SEP cover its expenses? How can it pay its authors? After all, credentialed, educated people don’t generally write 10,000-word articles for nothing. Not generally, they don’t, but in the specific case of the SEP, they do. Contributors are not paid. Instead of money, SEP offers its authors other rewards. Allen told the website Inside Higher Ed that he often coaxes reluctant authors by pointing out that a freely accessible entry in a popular online encyclopedia will be read by many more people than, say, an esoteric article in a paid-subscription academic journal. The SEP’s editors are not paid, either. Zalta has suggested that they may donate their time out of a sense of academic altruism, of bringing philosophy to the masses. Of course, the editorial board of the SEP definitely carries some cachet, and being a part of it would lend a bit of burnish to most academics’ CVs. Dorothea Frede, a professor of philosophy at the University of California at Berkeley and an SEP contributor, told me that because the SEP’s entries are recognized “as reliable and composed by experts,” the encyclopedia “enjoys international respect.” And so, too, do those affiliated with it, authors and editors both.

In its incipient days, the SEP covered its construction and operating costs through two major grants, one from the National Endowment for the Humanities, which granted $131,400 between 1998 and 2000, and one from the National Science Foundation, which gave $528,900 between 2000 and 2003. This money allowed Zalta to construct the efficient web content management system that would be crucial to the SEP’s successful functioning, especially now that the encyclopedia has well over seventeen hundred contributors. The SEP has received other grants as well. But the encyclopedia’s long-term funding model is more complicated than just relying on the winning of major monetary awards. In fact, the encyclopedia is currently building an endowment and has so far raised approximately 75 percent of the $4.125 million it seeks. The money has come, in large part, from donations from university libraries; over six hundred institutions have contributed. Stanford University itself has raised $1.125 million for the SEP endowment, and NEH chipped in a $500,000 Challenge grant. According to Ithaka, SEP’s “winning the support of the library community” for its “novel approach to sustaining an online resource” has been crucial to its fundraising success. The SEP’s yearly operating costs are approximately $214,000—that total includes personnel costs and $16,000 for administration and overhead. In 2008—2009, the SEP’s revenue included $160,000 from its endowment and $56,000 in direct funds from Stanford. Zalta hopes that soon the SEP will be fully supported by its endowment.

Is SEP the model for online encyclopedias—peer-reviewed, respected, accurate, and free? It might seem so, but experience suggests otherwise. In 2007, Sanger launched Citizendium, an online encyclopedia that sought to marry the collaborative nature of Wikipedia with traditional editing processes, much as the SEP does. Unfortunately, Citizendium currently has fewer than two hundred editorially approved articles. Sanger has all but removed himself from the project.

Perhaps, then, the success of the SEP is rather sui generis. Covering a relatively limited, esoteric subject in an online, editorially controlled encyclopedia based at a prestigious and well-funded university is one thing; attempting to cover all subjects in the same way is quite another. This in no way diminishes the work that Zalta and his colleagues have done. The SEP is a trailblazer, a dynamic reference that is always growing and developing, and one that may offer some hints about how, in the future, knowledge will be both presented and accessed.