In the mid-eighteenth century, the French man of letters Denis Diderot recruited his friends—and friends of friends—to write entries for his Encyclopédie. Twenty years and twenty-eight volumes later, 135 authors, including Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu, had contributed more than 71,000 entries.

Diderot wasn’t merely documenting the physical and intellectual world of his time, he was also sharing knowledge of it. The Encyclopédie brought Enlightenment ideas out of the salons and into the public square, challenging the power of the church and monarchy and laying the intellectual foundation for the French Revolution.

Jimmy Wales, the force behind Wikipedia.org, is the twenty-first century’s answer to Diderot. Instead of moveable type and a printing press, he has HTML and a server. Like Diderot, Wales has recruited everyone he knows—along with the rest of the world—to contribute to his free online encyclopedia. In a little more than six years, Wikipedia contributors have penned more than 1,671,000 entries in English. Wikipedia isn’t, however, limited to English. There are Wikipedias in 250 languages, ranging from German and French to Kirundi and Dzongkha.

Like Diderot, Wales is fomenting a revolution, but the only thing on this chopping block is the sovereignty of scholarly authority. The software that underpins Wikipedia enables users to add, edit, and delete content. This flexibility encourages a thriving community of knowledge that allows aficionados and academics to collaborate as equals. “It’s been a wide-open process where we invite the public to come and help us make it better,” he tells NEH Chairman Bruce Cole.

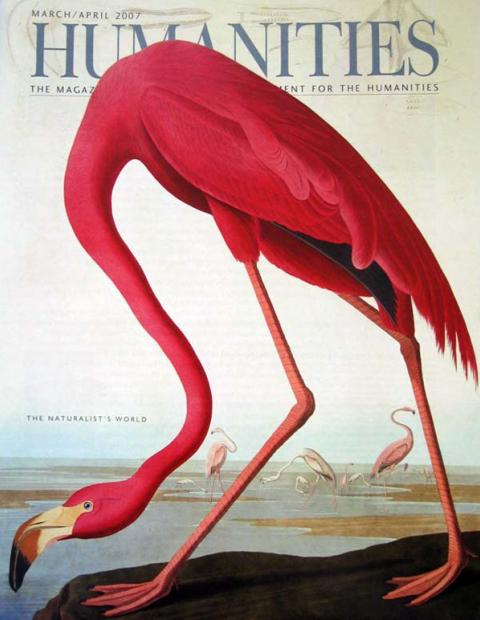

The advent of the Internet has made the world a less mysterious place. With the point and click of a mouse, you can learn everything there is to know about the bald eagle or the flamingos of Florida. In the early nineteenth century, the most reliable source would have been John James Audubon. A new NEH-supported film, John James Audubon: Drawn from Nature, looks at the life of the artist, explorer, and businessman. Audubon spent more than a decade drawing and annotating Birds of America, a seven-volume set of 650 hand-colored prints that capture the birds in their natural habitat. Although Audubon is known for his beautiful drawings, he also wrote lively descriptions of the birds’ behavior based on his field observations.

Audubon was not the only one interested in documenting the biological wonders of North America. While Diderot was writing his entries, Swedish scientist Carolus Linnaeus was classifying plants and animals, creating the taxonomy still used today. To support his project, he sent his students out into the world to collect plants. “Come into a New World: Linnaeus and America,” an exhibition at Philadelphia’s American Swedish Historical Museum, follows the path of Pehr Kalm, one of Linnaeus’s students, on his three-year trek across the North American wilderness. Kalm’s journals documenting his expedition were translated into five languages.

As the editor of Humanities for seventeen years, Mary Lou Beatty relished playing with ideas and never hesitated to ask “why?” Mary Lou passed away in early February after a long battle with cancer, making this the last issue in which she was intimately involved. The absence of her wit and grace are keenly felt, but her memory continues to inspire.