Voices for the Future

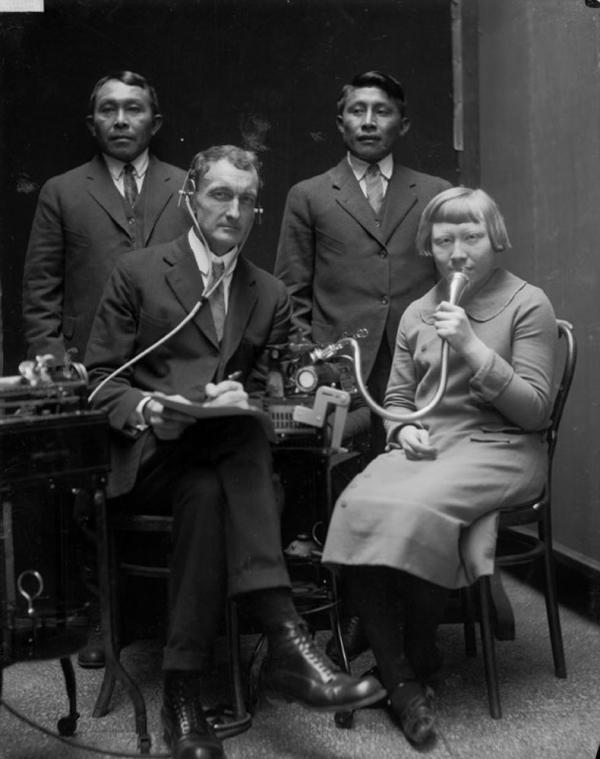

J. P. Harrington and Tule Indians pictured with language recording equipment.

Courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

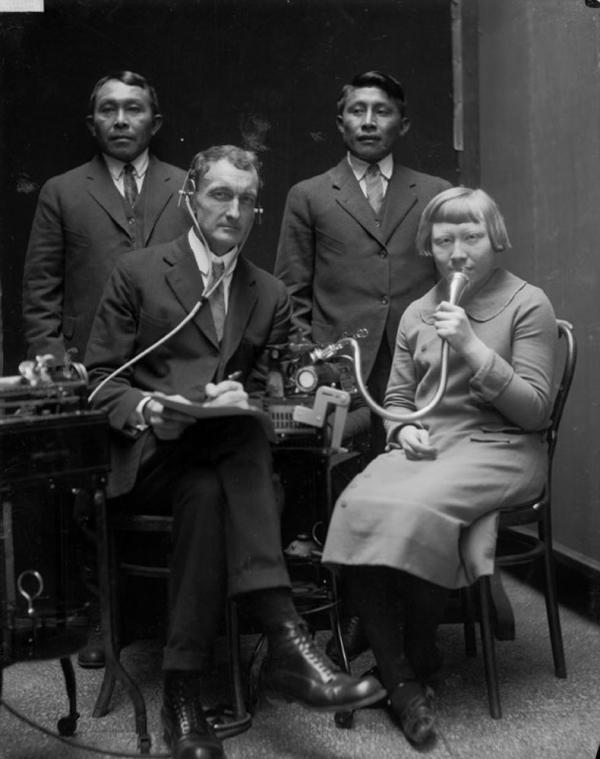

J. P. Harrington and Tule Indians pictured with language recording equipment.

Courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

California is home to greater linguistic diversity than any other U.S. state. As such, it has long been a fruitful site for scholars interested in studying and documenting the state’s native languages. About 90 indigenous languages are known to have been spoken in California, representing one third of the language families identified in North America. Fifty percent of California’s indigenous languages no longer have native speakers.

For more than one hundred years, linguists at the University of California, Berkeley, have been documenting the state’s endangered languages. Their work has been deposited with the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages (SCOIL), a research archive at the Linguistics Department, as well as at the Berkeley Language Center (BLC), the Bancroft Library, and the Hearst Museum of Anthropology.

In 2007, the University of California received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities through the Documenting Endangered Languages program (DEL) to improve access to linguistic materials held at the Berkeley repositories, including fieldwork notes, manuscripts, and audio recordings that document over 130 endangered American Indian languages from North America. Berkeley linguists Andrew Garrett and Leanne Hinton directed the project. Thanks to the NEH grant, incompatible catalogs, which complicated previous consolidation efforts, are now searchable through a single portal, the California Language Archive (CLA). (The CLA site is open to the public, though full access to some items requires free registration)

The CLA site features audio recordings and digital images that document fifty languages indigenous to California and another eighty from nearby regions. Users may search and browse the collection by consultant, researcher, and language. In addition, a map interface allows users to explore the geographic distribution of Indian languages. Online material is now presented directly to users of the CLA, which, according to project co-director Andrew Garrett, “unlike many language archives, presents content in straightforward terms so that non-academic users are not intimidated.”

Documenting Indigenous California Languages

Language documentation and collection has a long history in California going back a century to the work of the celebrated anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber, who founded the Archaeological and Ethnographic Survey of California, the precursor to SCOIL, in 1901. Other scholars who have also undertaken major documentation efforts include J. P. Harrington, a noted linguist with the Bureau of American Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution (see image above), who documented Chochenyo (also spelled Chocheño), an indigenous language spoken in the East Bay of San Francisco. Collected in the 1920s, Harrington’s original field notes represent most of the documentation that currently exists for that language. The notes show Harrington’s work with consultants María de los Angeles Colós and José Guzman and have been used by the Muwekma Ohlones tribe in its language restoration programs.

In the late 1950s, Robert Oswalt carried out documentation work on Kashaya Pomo (see image above), largely in collaboration with consultant Essie Parrish (see image above). Kashaya, a Southern Pomoan language, was spoken along the Pacific coast in Sonoma County, from north of Bodega Bay to Stewart's Point and Annapolis, but today only several dozen first-language speakers remain. Parrish was known as a basketweaver as well as an educator, as illustrated in her telling of how the Kashaya became acquainted with non-Native foods, recorded by Oswalt in 1958, which offers the rare opportunity to hear an extended example of spoken Kashaya.

Also, from the 1950s to the early 2000s, William Bright collected material on Karuk, a language traditionally spoken by the Karuk people in northern California along the Klamath River between Seiad in the north and Bluff Creek in the south. Bright collaborated with various consultants, and is shown here working with a group of Karuk speakers (see image above). A notable repertory of songs in Karuk was recorded by Bright, as in this example of a Karuk love song sung by Chester Pepper. In the song’s emphatic rhythmic pattern, each strong beat is subdivided by three pulses, and throughout Pepper alternates his voice between two singing styles, the first exuberant timbre in a higher register leading each time to a second, hushed intonation in a low register.

Revitalizing Indian Languages

The urgency to document California languages was voiced by Franz Boas, Kroeber’s teacher at Columbia, who opined in April 1901: “it is only a question of a very few years when [California Indian] languages . . . will have disappeared.” The archival materials at the CLA collected during these early years form the essential foundation for recent linguistic research and also support the work of tribal groups seeking to revitalize their ancestral languages.

Since SCOIL was founded more than a century ago, there has been a marked increase in engagement between linguistic researchers and Native language communities. Many heritage speakers, who may not have grown up speaking ancestral languages, find inspiration in the documentation produced by academic linguists. SCOIL has actively engaged Indian groups in language revitalization since the 1980s. Under the leadership of director emerita Leanne Hinton, SCOIL has hosted workshops throughout California, invited tribal representatives to visit its archives, and sponsored a biennial Breath of Life workshop for communities in which no native speakers remain. Hinton has also worked on documenting Havasupai, a Yuman language of Arizona. The results of her efforts are now digitized and browsable through the CLA (see image above). In a 1974 audio recording with consultant Edith Putesoy, we hear the detailed work of eliciting vocabulary through an interview as Hinton says an English word, followed by Putesoy’s spoken response of a corresponding word in Havasupai, repeating each word twice as an aid for pronunciation and later transcription.

Reflecting on the significance of the NEH support for the CLA, co-director Andrew Garrett reflects, “several of us involved in the [NEH] project have had the experience of showing members of Native communities how to use the CLA, and watching them navigate among resources. . . . We have seen people who were thrilled to discover that their own grandparents or great-grandparents had been recorded . . . telling stories, or even giving a word list or simple conversational vocabulary.” The CLA moves this academic work into a second century with a mandate to keep these languages available and return them to the communities in years to come.

Documenting Endangered Languages

The DEL program is a partnership between the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) to develop and advance knowledge concerning endangered human languages. Made urgent by the imminent death of an estimated half of the 6,000–7,000 currently used languages, this effort aims also to exploit advances in information technology. Awards support fieldwork and other activities relevant to recording, documenting, and archiving endangered languages, including the preparation of lexicons, grammars, text samples, and databases.

For more information on notable language revitalization efforts currently underway, such as those featured at the 2013 Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, DC, go to One World, Many Voices, to learn about how culture bearers use ancestral languages to “embody cultural knowledge, identity, values, technologies, and arts.”