The Dictionary of American Regional English: Recent Developments

Dictionary of American Regional English

Dictionary of American Regional English

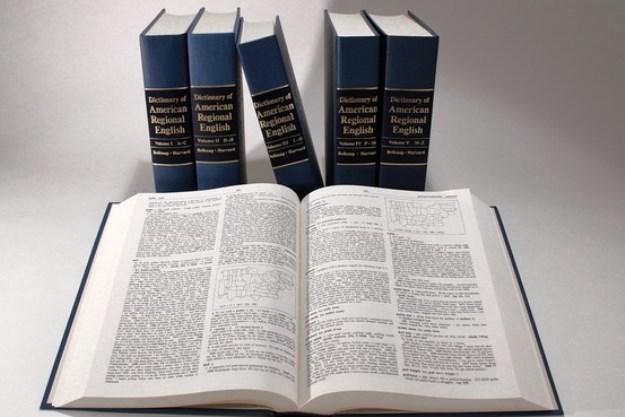

2013 was an annus mirabilis for the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE), a major reference resource widely used by scholars and members of the general public, and supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities. The Reference and User Services Association (a division of the American Library Association), awarded the staff of DARE, which is based at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, the Dartmouth Medal for the “creation of a reference work of outstanding quality and significance."

VOLUME VI

2013 was a landmark year for another reason. With the publication of the sixth and final volume of the dictionary in January, DARE has achieved its goal of developing a resource that explores the rich variety of regional vocabulary in the United States. (For information on the history of DARE, see Michael Adams’ feature in Humanities Magazine, “Words of America: A Field Guide.”)

The most recent volume offers a full index of words from A to Z that are used in a particular place, as well as terms that came into American English from other languages. In addition, Volume VI contains maps that visualize nationwide patterns of language use.

The origins of DARE go back nearly fifty years. In 1965-70, DARE fieldworkers interested in documenting the ways Americans actually spoke fanned out across the country to conduct interviews with people using a questionnaire designed to elicit language used in daily life. Questions included ways in which people in different parts of the country described various subjects: from time and weather to household items, farming, trees and flowers, birds and insects, school, courtship and marriage, religion, health, and money. The results revealed the rich regional diversity of American English.

DARE WEB SITE

DARE has recently made the transition from being available in print only to providing online access as well. In early December, the long-awaited digital version of the dictionary was launched—an interactive, multimedia tool that provides access to all entries and to the materials collected to produce the dictionary. Although full access to the digital version of DARE requires a subscription, numerous features are available gratis to visitors to the Web site (http://www.daredictionary.com/). For example, one can browse headwords through the Word Wheel; see 100 free entries; identify all the entries from a given state or region; search the bibliography; and use the “Resources” tab to view the materials found in Volume VI. Subscribers can carry out advanced searches by full text, headwords, variants, definitions, etymologies, parts of speech, quotations, regional labels, and social labels, as well as use filters and Boolean options to refine search criteria. And finally, visitors to DARE’s Web site can discover related audio recordings, maps, and data from respondents to the DARE questionnaires. All future updates to the DARE will be made through this online reference resource.

SPANISH LOAN WORDS IN AMERICAN ENGLISH

As noted, the most recent volume of the dictionary includes an index of those terms that have entered American English from other languages—terms that have their origin in the speech and cultural practices of the various groups that have contributed to the American experience. An exploration of DARE’s Web site offers many examples of borrowing from other languages. Should you do a full-text search for the word “Spanish,” for example, you will encounter a variety of terms that reflect the strong imprint of Spanish and Latin American settlers and immigrants in the United States, especially in the Southwest.

Some of these words relate to the geography of the region: “alberca” (water hole or pocket, watering place), “cienaga” or “senaca” (marsh or swamp), “laguna” (pool or pond of salt or fresh water), “tinaja” (water hole), and “vega” (grassy plain, meadow). Others pertain to fauna and flora: "vinegarone” (whip scorpion), “paloverde” or “retama” (Jerusalem thorn), and “alegria” (amaranth), especially as used in candy. The list of Spanish loan words includes farming terms used by settlers such as “acequia” or “zanja” (irrigation ditch) and “milpa” (cultivated patch), which in Texas has come to signify a land measure of 177 acres. Spanish terms for building features that have entered American English include “hacienda” (main house of a ranch or estate), “jacal” (hut usually built with mud and roofed with thatch), and “viga” (roof-beam used in American Indian and Spanish colonial-style architecture).

Ranching and mining were the primary economic activities in the Southwest for the early Spanish settlers, so it is understandable that we have borrowed from them many words that are broadly used: such as “ranch,” “wrangler,” and “pinto." Others may be less well known but are part of the regional vocabulary: “atajo” or “hatajo” (a string of pack animals), “caballada” or “cavvy” (a group of saddle horses or mules), “leppy” (orphan calf, lamb, or foal), and “sabina” (red-roan coat animal, especially one with white markings).

A number of common mining terms are derived from Spanish and are documented in 19th-century newspapers. In fact, newspapers are an excellent resource for understanding the evolution of language. The Chronicling America Web site, which is maintained by the Library of Congress and supported in part by the NEH, provides free access to millions of pages of historic American newspapers from 1836 to 1922. Through a simple search you see how new words entered our vocabulary. During the boom and bust of silver mining in Nevada during the 1870s and 1880s, for example, several Spanish loan words became current: including “placer,” which refers to a deposit of sand or gravel where particles of gold are found; the gold itself; and in combination with “mining,” a method of extracting gold by washing. Also notable is the term “borrasca,” which, according to DARE, refers to “an oreless mine or mine section,” or “a state of unproductiveness.” A news item in the Troy Weekly Kansas Chief from 1875 observed that if “a miner was searching at great expense and in disappointment in the barren vein stone for material that would pay, he said the mine was in a borrasca.”

DARE entries also document Mexican and Latin American foods now popular across the nation, as well as some words whose Spanish origin may not seem obvious; for example, “jerky” (meat preserved by drying, especially in strips in the open air) comes from the Spanish “charqui” (see map showing usage). Some specialty foods listed in the dictionary include: “nopal” (prickly pear cactus, especially the flattened joint of this plant), “piloncillo” (unrefined sugar, usually in the form of a cone or loaf), and “sotol” (a liquor made of a yucca-like southwestern plant also called bear grass).

Among DARE entries, one also finds terms related to holiday traditions such as the “posadas” (pre-Christmas visits made to the homes of friends) and “luminarias” (a small bonfire lit as part of a Christmas Eve custom, chiefly in New Mexico). Also listed are lesser-known customs; for instance, the practices of the “penitentes,” a religious society of Flagellants earlier condemned by religious and government officials and the festive tradition of the “cascarones.” The latter was a Mexican tradition that was widely practiced in California during dances; it consisted of breaking an eggshell filled with confetti on someone’s head as a compliment.