Bonfires, Greased Pig Races, Pickle Contests, and More: Historic Fourth of July Celebrations from Chronicling America

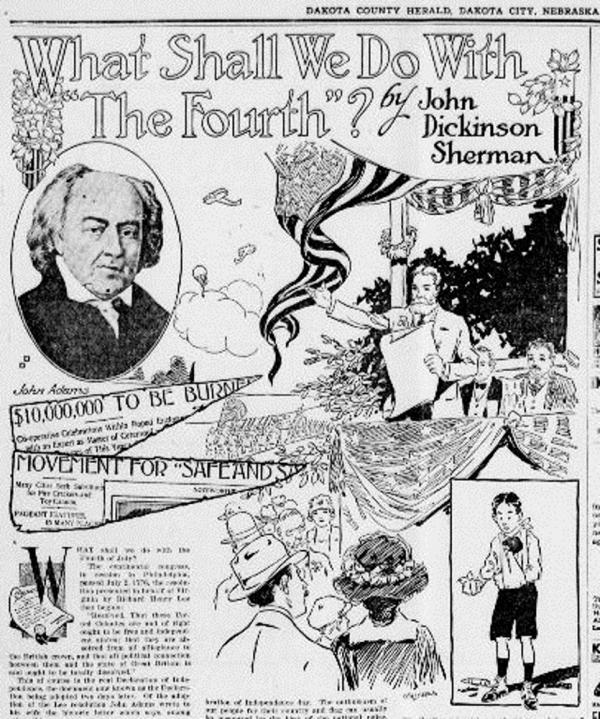

What Shall We Do With the Fourth? Dakota County Herald. (Dakota City, Nebraska) June 24, 1920.

Courtesy of Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress Image provided by: University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries, Lincoln, NE

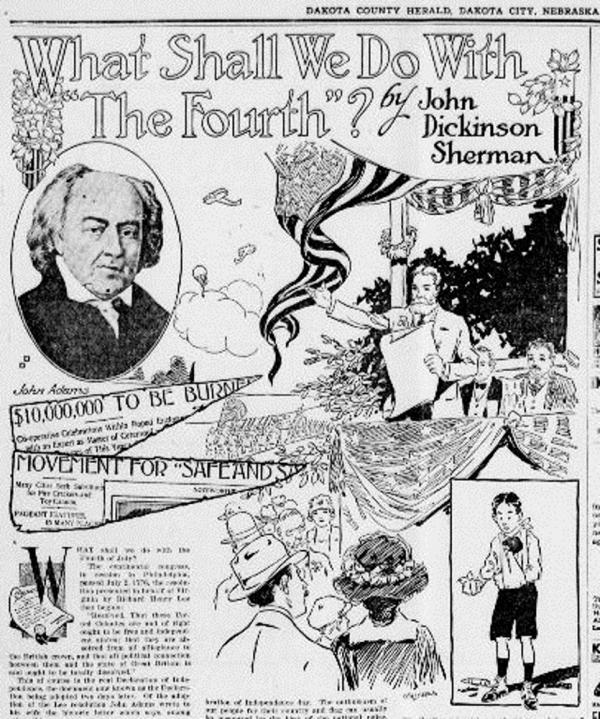

What Shall We Do With the Fourth? Dakota County Herald. (Dakota City, Nebraska) June 24, 1920.

Courtesy of Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress Image provided by: University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries, Lincoln, NE

When was the last time you celebrated the Fourth of July by participating in a greased pig competition, a velocipede race, or a pickle contest? How about by enjoying a dinner of chicken and ham in jelly, Salad Yorktown, and bombe Africaine? Did your holiday plans involve listening to a public reading of the Declaration of Independence or an oration? John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail in 1776 that the signing of the Declaration of Independence should be “solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward, forevermore.” The historic newspapers in Chronicling America reveal that over time, Americans have interpreted this celebration in very different ways.

What is Chronicling America?

Chronicling America is a freely accessible Web site providing information about and access to historic United States newspapers published between 1789 and 1924. To date, nearly 12 million pages representing 41 states, 1 territory, and the District of Columbia are available on the site. Chronicling America is produced through the National Digital Newspaper Program, a partnership between the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and state projects. NEH awards enable states to select and digitize newspapers that represent their historical, cultural, and geographic diversity, and to contribute essays containing background information about each newspaper and its historical context. The Library of Congress unifies all content provided by states and permanently maintains the digital information. Chronicling America is freely available on the internet, and users may search the millions of digitized pages and consult a national newspaper directory to identify newspaper titles available in all types of formats.

Picnics, Politics, and Processions

Before the Civil War, celebrations, often organized by town committee like the one in 1843 in Yazoo, Mississippi, involved processions, military salutes, and ringing of bells, public readings of the Declaration of Independence, and barbecue dinners with toasts. The Fourth of July procession in Abbeville, South Carolina, in 1846 ended in a grove where “a large concourse of ladies, comprising the chief beauty and intelligence of the District, [were] already congregated, and anxious to honor the occasion, with their presence and approving smiles.” Some locales used the occasion for political meetings, such as an 1840 “Log Cabin Raising” in Brattleboro, Vermont held by the Whigs. Americans from Hawaii to Indiana to New York also celebrated with picnics, sumptuous dinners, and boat excursions—although sometimes overindulgence in alcohol led to “behavior unbecoming the Fourth of July.” Advocates of Temperance, a movement gaining steam throughout the 19th century, held their own picnic in Carthage, Ohio, in 1853, while an anti-temperance speaker in Tennessee urged Americans to “let the Fourth of July go on,” drink and all. As the country became increasingly divided by sectional strife in 1859, the Randolph County Journal in Winchester, Indiana, “rejoiced that there was at least one day in the year when they could meet and mingle together their friendly greetings, free from partisan strife and sectional animosity.” The town voted that the next year they would celebrate Independence Day “in the old fashioned style.”

Jumping Skubeen or a Tub Race?

Celebrations got increasingly creative later in the 19th century, often reflecting local amusements, the meanings of some of them lost today. While readings of the Declaration of Independence and orations were still featured, Independence Day festivities increasingly included fireworks, contests, games, and shows. For example,

- The 1872 celebration in Petroleum Center, Pennsylvania, included a “grand explosion of torpedoes and Chinese crackers,” music, singing, a grand footrace, a baseball game, a velocipede race, a grand balloon ascension, a picnic, and a contest of “turning flip flaps through an iron hoop” for which the prize was a “diamond studded leather medal.” In addition, the account published in the Petroleum Center Daily Record promised, two “renowned acrobats and gymnasts” would “turn a double handspring from the brick bank building to the Boyd farm bridge.”

- An 1880 ad in the St. Paul [Minnesota] Daily Globe promised a race after a greased pig, a “Tub Race, by Six Experienced Tubbists,” as well as “Quoits, Throwing Heavy Weights, Jumping Skubeen,” and other amusements.

- Meanwhile, in 1891 the Anaconda Standard reported on Independence Day celebrated “Rocky Mountain Style” in Granite, Montana, featuring a drilling contest, wrestling, throwing hammer, stone throwing, a foot race, and a baseball game.

- According to Arizona’s Mohave County Miner, crowds attending the Fourth of July festivities in the town of Kingman, in 1897, would be treated to the “Third Annual Advent of Beautiful Queen De Cacti and Body Guard of 100 Warriors in Gaudy Costumes,” a “Cowboy tournament by Crackajack Cowboys,” and a “Balloon ascension by Mlle. Sibyl Anderson, the bewitchingly beautiful and world renowned aeronaut,” as well as greased pole and greased pig competitions and a burro race.

- Many celebrations of this era, such as this one from Flagstaff, Arizona, included a hose contest which involved unreeling fire hoses.

- Bonfires were the order of the day in Salem, Massachusetts, with one in 1899 constructed of 4,000 whiskey barrels.

You’ll Just Have to Yell, If You’re Overenthused

Home use of fireworks grew in the 19th century, and explosions were linked to patriotism as in this 1896 fireworks ad declaring “Hurrah for the republic of Hawaii!” Such merriment was not necessarily safe, however, and according to the New York Tribune, between 1903 and 1909 1,316 people died and 27,980 were injured in Fourth of July celebrations. A poem published in 1912 in a Chicago newspaper began “It’s coming, it’s coming, hear everyone cry, the long `waited breath-bated Fourth of July, the glorious Fourth, the ‘worrious’ Fourth, that blows off your fingers and shoots out your eye.” An article appearing in 1900 in the Pullman [Washington] Herald contains a lamentation that the “opening of trade with China brought in the small firecrackers and American factories soon found the means of making big ones. Noise assumed the scepter and has reigned ever since.” In the early 20th century, the Safe and Sane movement began in cities and towns such as Springfield, Massachusetts, Detroit, Michigan, and Hinsdale, Illinois. It proposed a more sedate celebration of Independence Day, advocating historic pageantry rather than the “usual carnival of noise and destruction of life, limb and property.” A 1914 Chicago paper even printed this inspiring poem, entitled “WE’LL ALL HAVE BOTH EYES AFTER THE FOURTH OF JULY”:

Nix on the lockjaw,

Nix on the maim,

Loud noise explosives

Are out of the game.

Fourth of July scares

Have all been excused,

You’ll just have to yell

If you’re overenthused.

As the San Francisco Call sensibly argued in 1912, “After all, it is better to have all our fingers and toes and our eyes and a few other necessary things on the fifth of July than to have firecrackers and caps on the fourth. So the best thing we can do is to accept the safe and sane fourth gracefully and look around for whatever nice noise making devices are left to us among the perfectly safe explosives.”

Holidays, Like Men and Nations, Do Not Stand Still

The Safe and Sane movement prevailed in the coming years, though not without its detractors. While Independence Day continued to feature fireworks shows, programs intended to draw people away from private experimentation with explosives through even more public contests, shows, and demonstrations that had been present since the mid-19th century. In 1919, for example, the residents of Hayti, Missouri could participate in a fat man’s race (prize: cigars), a sack race for boys (prize: candy), a pickle contest for girls (prize: silk hose), and an egg and spoon race for women (prize: silk hose); in addition the organizers of the festivities promised “Patriotic, Pulse-Stirring Music Throughout the Day by the Old Reliable Hussar Band.” Abbeville, Louisiana, boasted an aviation demonstration, while Glasgow, Montana, suggested “something worth seeing”: an automobile barrel race and a bucking contest “with outlaws that have never been ridden.” The 1919 Fourth of July celebration in Mt. Sterling, Kentucky, included a “baby show,” while the 1920 festivities in Caldwell, Idaho, showed a particular respect for the town’s elders by offering cash prizes to pioneers residing in Idaho since 1875 (the “four pioneers in each car whose combined ages are highest” would be the prize winners). Caldwell also offered prizes for best schools on wheels or cars and sponsored a water fight by the city fire department. Racing and the Fourth of July went hand in hand. In 1922, the Grand Celebration in Mansfield, Missouri, offered a young ladies’ race, fat man’s race, boys’ and young men’s races, and other contests, and those celebrating the holiday at Cape May, New Jersey, could participate in many foot and boat races.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Fourth of July celebrations were different all over the country. Find out more about how the Fourth of July was celebrated in your neck of the woods by searching Chronicling America for “Independence Day” or “Fourth of July.” Using the Advanced Search tool, you can search for celebrations in your state or for a specific year, such as the Centennial Year of 1876. See the Library of Congress’s Topics in Chronicling America page for more search tips and suggested articles.

Happy Independence Day!