ODH Project Director Q&A: Ryan Cordell

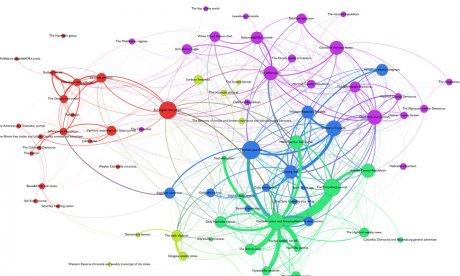

A visualization of 19th-century reprinting networks among United States newspapers in the Chronicling America collection. The larger circles or nodes represent newspapers that published stories, poems, and other items most frequently reprinted in other newspapers.

Photo courtesy of Ryan Cordell

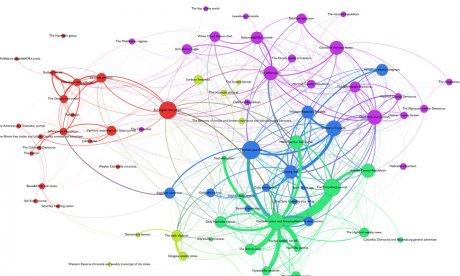

A visualization of 19th-century reprinting networks among United States newspapers in the Chronicling America collection. The larger circles or nodes represent newspapers that published stories, poems, and other items most frequently reprinted in other newspapers.

Photo courtesy of Ryan Cordell

In our ongoing series of interviews with recent Digital Humanities Start-Up Grants awardees, this week we've asked Ryan Cordell, project director of "Uncovering Reprinting Networks in Nineteenth-Century American Newspapers," to answer a few questions. Together with collaborators Elizabeth Maddock Dillon and David Smith of Northeastern University's NULab for Texts, Maps, and Networks, Cordell is exploring how stories, poems, and news items circulated among American newspapers in the 1800s. Using advanced computational methods to analyze the large-scale collection of digitized newspaper pages in Chronicling America, a joint project of the NEH and Library of Congress, the project team is exploring cultural and literary trends in 19th-century America as well as individual texts that may have circulated widely but have since been largely overlooked by researchers. Through this work, the team hopes to shed light on not only which texts were reprinted across newspapers, but also what factors prompted editors to reprint (with and without attribution) pieces from a complexly interconnected, geographically diverse web of sources.

Follow the project's progress at http://www.viraltexts.org/.

ODH: What are some good examples of literature or news stories that “went viral” in 19th century publications?

Ryan: We're finding a wide variety of texts that "went viral": poems, short stories, news, travel accounts, "how to" pieces, political speeches. One of the most interesting genres has been what we're calling vignettes. These are short prose pieces, typically one-three paragraphs long, and typically anonymously authored. They read a bit like news pieces and bit like fiction. For instance, one very popular vignette claimed to be a letter, written "by a dying wife to her husband" and found by him on her pillow after she died. In the letter she recounts her love for him and counsels him about living a moral life after she has passed away. While this vignette claims to be transcribed from a letter, the piece gives no details—the name of the husband or wife, the town in which they lived—which would allow readers to verify the story. Nineteenth-century newspapers were hybrid publications. They included news, fiction, poetry, and many other genres of writing which as modern readers we don't associate with the newspaper. These vignettes seem to embody the hybrid media in which they appeared: they are simultaneously news and fiction, true and false.

Another good example is "The Inquiry," which was the title given to a religious poem by the Scottish poet Charles Mackay. This poem demonstrates the ways that pieces changed as they circulated around the country. In this case, the first line of the poem is edited as the poem circulates, changing from "Tell me, ye winged winds" to "Tell me, ye winding winds" within a few weeks of its first publication. What I find interesting is that the edited version becomes the most popular version—it's actually printed far more times than the original. In the antebellum press, texts and authorship aren't stable—both are continually changing as pieces are reprinted, reauthored, and reappropriated for the varied purposes of readers and editors.

ODH: How might the computational methods you propose augment what scholars already know about republication practices and 19th-century American culture more broadly?

Ryan: There have been really several fabulous studies of antebellum reprinting. My touchstone is Meredith McGill's American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting. As McGill says in that book, however, those studies have been bound by very human limitations. There are millions and millions of newspaper and magazine pages from the period, far more than any scholar could study in a lifetime. Because the archive—and here I mean the print, microfilm, and digital archive—of periodicals is so vast, it's also not well indexed. To find these short reprinted texts from periodicals across the country would require many lifetimes of continuous reading and annotation. In many ways we hope to test and extend the work that scholars have done on republication by testing their ideas across an entire corpus. By looking at reprinting systemically, we expect new questions to arise about how reprinting practices intersected with other social, political, technical, and religious systems.

ODH: What are some of the challenges involved in a project like this one? How are you tackling these?

Ryan: There are many challenges here. Working effectively across three disciplines (our team is comprised of historians, literary scholars, and computer scientists). Finding meaningful patterns in very messy data—though I should say that the fact that the data is so messy is partially why my computer science colleague, David Smith, was interested in working on the project! One of our biggest challenges is access. We've started our work using the Library of Congress' Chronicling America newspaper archive. We've been able to find many, many viral texts, but we're painfully aware of how incomplete that collection is. Chronicling America is based on state-level digitization projects, and there are huge holes, either because a given state hasn't digitized its newspapers or because their newspapers were digitized by commercial archives who don't make the data available to researchers. We don't have any newspapers from Georgia, or from Michigan, or even from Massachusetts. These and other state-sized gaps prevent us from building a truly national picture of antebellum reprinting. Right now we're talking with several commercial archive providers about getting access to their data, but it's been a slow and often frustrating process.

ODH: In what ways does this project complement other efforts making use of Chronicling America, such as the NEH-funded Mapping Texts and Epidemiology of Information: Data Mining the 1918 Influenza Pandemic?

Ryan: Along with projects like Mapping Texts and Epidemiology of Information, our viral texts project demonstrates the potential that large-scale collections of humanities data for asking new kinds of questions. When you can search for patterns across very large corpora, you can uncover system-wide phenomena that are obscure at the level of an individual newspaper issue or series. One thing we've done with our initial findings is use the thousands of reprinted texts we've uncovered to map the network of antebellum print. We use shared reprints (reprinted texts that appear between two publications) to map influence across the system. These network graphs begin to illustrate which newspapers shaped the network: which papers printed texts that many other newspapers also printed. We're already finding some surprising results. Newspapers that haven't been well studied by scholars—in cities such as Nashville, Tennessee and Glasgow, Missouri—are proving more central to the network than we expected going into this project. As we annotate our data we'll be able to make more subtle analyses: tracking whether the political affiliation of newspapers shaped their network of reprinting, for instance. In this way, we're building on the work of projects like Mapping Texts and Epidemiology of Information to consider newspapers systemically, rather than reading them selectively.

ODH: How might this project benefit humanities scholars hoping to adapt your methods as they pursue different research questions, whether using Chronicling America newspapers or other large-scale collections of digitized humanities materials?

Ryan: Though it may seem a more obscure benefit, I think our project is a model for effective cross-disciplinary collaboration, particularly between humanities scholars and computer scientists. These kinds of collaborations can be difficult to make work—all parties need to be intellectually invested in the project and building toward publishable results within their respective fields. It's important that the collaborators recognize this and keep that end in view throughout. Humanities scholars can't work with computer scientists if they expect their CS colleagues to work as programmers for humanities projects. There must be intellectual stakes on the CS side as well.

Beyond this, I hope our project can demonstrate the real payoffs that complex pattern analysis using digital corpora might hold for literary and historical scholarship. Often the only example scholars have seen of this kind of work is the Google N-grams Viewer, a tool which one can use to track the rise and fall of particular words and phrases within the Google Books corpora. While it's fun software to play around with, the Ngrams Viewer is ultimately of limited use for scholars, primarily because it provides no way for researchers to dig into the books behind the charts or explore the context for the trends the charts suggest. Our project makes use of similar techniques, but in service of a specific and (we think) important question for scholars of nineteenth-century America—a question that couldn't be answered without computational linguistics tools.

Finally (and briefly), we are building a web interface for our results at viraltexts.org. We've already uncovered far more viral texts than we can analyze, and we know that other scholars will find interest in texts or aspects of texts that we missed. We hope that historians, literary scholars, and others will be able to use our data to ask and answer questions we didn't even consider.