In an 1830 essay called “London Solitude,” the English writer William Hazlitt considered a profound paradox of urban life—namely, that in one of the most populated places on earth it’s still possible to feel vividly and sometimes painfully alone.

“In London,” Hazlitt tells readers, “anything may be had for money; and one thing may be had there in perfection without it. That one thing is solitude.” It’s the kind of aloneness, he notes, that not even the countryside can offer:

Take up your abode in the deepest glen, or on the wildest heath, in the remotest province of the kingdom, where the din of commerce is not heard, and where the wheels of pleasure make no trace, even there humanity will find you, and sympathy, under some of its varied aspects, will creep beneath the humble roof.

Compare that, Hazlitt says, with the isolation that falls on a soul in a city:

But in the mighty metropolis, where myriads of human hearts are throbbing—where all that is busy in commerce, all that is elegant in manners, all that is mighty in power, all that is dazzling in splendour, all that is brilliant in genius, all that is benevolent in feeling, is congregated together—there the pennyless solitary may feel the depth of his solitude.

“London Solitude” is one of Hazlitt’s shortest essays, only about a page long. The piece isn’t included in many anthologies, perhaps because its brevity doesn’t, at first glance, suggest the kind of ambition that defined Hazlitt’s longer works.

Like a compact and well-crafted poem, “London Solitude” achieves its effect, however, by acute distillation rather than large scale. It’s an apt introduction to the qualities that underscore Hazlitt’s reputation as a master essayist.

For one thing, his gift as a stylist is on full display. Notice how, in his sentence on the “mighty metropolis,” he uses a seemingly endless succession of asides to simulate the crowded, cosmopolitan abundance of London. That little word, “all,” repeated again and again, also suggests an impressive infinitude. There is nothing, or so it seems, that the city can’t offer. Then this cornucopia ends rather abruptly with the image of a poor hermit at the margins, untouched by the innumerable possibilities of personal connection that London lavishes on the lucky. Rhetorically, the sentence begins in a river and ends in a drought, a contradiction coiled at its core like a spring, ready to surprise the unwitting reader.

This kind of ingenuity has made Hazlitt something of a writer’s writer, endearing him to fellow scribes who have a special admiration for his technical skill.

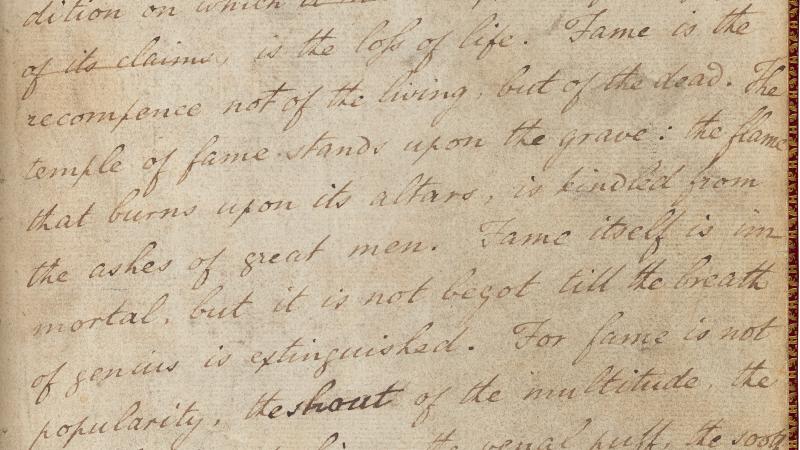

Hazlitt himself was a perceptive student of style. Writing of Edmund Burke, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and statesman, Hazlitt offered this famous observation: “Burke’s style was forked and playful as the lightning, crested like the serpent.” Virginia Woolf admired that sentence, as does Clive James, who floats it in the middle of his essay on Hazlitt, as if hanging a prized canvas.

“What an electrifying thing to say,” remarks James, who’s no pushover as a critic. “I not only thought so when I first read it, but the actual word ‘electricity’ came into my mind, no doubt because the word ‘lightning’ was already there on the page.”

James homes in on Hazlitt’s signature tactic, the way he often posits opposing images within the same breath. There’s the lightning bursting out of nowhere, and the snake still biding his time, waiting for the moment to strike. Here’s how James summarizes the shock of his initial meeting with Hazlitt’s Burke sentence:

What mattered was the balance between the two pictures. The first picture was of things happening very quickly at random, and the second was of a pause, a poise. These pictures were matched by the two contrary movements of the sentence, prancing up to the comma, and then turning deliberate after it. Hazlitt had paid Burke’s style the double compliment of contesting it with a well-crafted sample of his own.

The other thing about “London Solitude” is how familiar its theme sounds. It invites an obvious comparison with E. B. White’s “Here Is New York,” a celebration of Gotham that White wrote in 1948. White, too, noted the prospect of solitude in a city teeming with multitudes. “On any person who desires such queer prizes,” he writes in a much-quoted insight, “New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy. . . . The capacity to make such dubious gifts is a mysterious quality of New York. It can destroy an individual, or it can fulfill him, depending a good deal on luck.”

Edward Hoagland, writing of New York in 1969, strikes a similar note, concluding that in spite of—or perhaps because of—the congested Manhattan streets, “(m)ost of the vogues were vogues in loneliness.”

When White and Hoagland wrote of city life, their attention to the puzzle of feeling alone in a crowd seemed concerned with a problem posed by the twentieth century and its peculiar brand of malaise.

Hazlitt, however, writing an ocean away from the Big Apple and more than a century before White, takes the subject as his own. It’s just one example of the way in which Hazlitt can sound thoroughly contemporary in spite of his nineteenth-century moorings.

Do we grieve over today’s partisan divisions? Hazlitt, writing in 1830, reminds us that the challenge is nothing new. In an essay called “Party Spirit,” about the political divide in his time and place, Hazlitt analyzes the tendency “to prove that we, and those who agree with us, combine all that is excellent and praiseworthy in our own persons . . . and that all the vices and deformity of human nature take refuge with those who differ from us.”

Hazlitt, in that same essay, also astutely pinpoints the issue of political correctness, another phenomenon widely assumed to be a current invention: “We may be intolerant even in advocating the cause of Toleration, and so bent on making proselytes to free-thinking as to allow no one to think freely but ourselves.”

To read Hazlitt is often to feel the chasm of years instantly collapse, bringing him beside us. He can sound, for all his period references, compellingly up to date. The word “modern” is attached to Hazlitt so frequently that it can sometimes feel like part of his name. Historian Paul Johnson hailed him as “a truly great writer, perhaps the first truly modern writer in England,” a conclusion that gets a thumbs-up from critic Joseph Epstein. “Among Hazlitt’s contemporaries,” Epstein notes, “Coleridge was certainly more wide-ranging, Wordsworth in his particular line deeper, [Charles] Lamb more winning. But Hazlitt . . . feels more like our contemporary, which is another way of saying that he seems more modern.”

Duncan Wu picks up the theme in William Hazlitt, his 2008 biography of the writer that’s predictably subtitled The First Modern Man. “His commentaries on government spies, the hereditary monarchy, and the Church remain relevant nearly two centuries after their first publication,” Wu writes. “And like all great writers Hazlitt had an intuitive understanding of human psychology that, despite the passage of time, gives his writings a resonance and urgency lacking from those of his contemporaries. In that sense the most memorable of his subjects was himself.”

Both Wu and James credit Hazlitt with helping to invent modern journalism, an innovation also suggested by “London Solitude.” Instructively, in spite of its introspection, the little essay points the reader outward, into the city streets. It affirmed Hazlitt’s abiding belief that culture did not simply grow in the theaters where he wrote about plays or in the books that he perceptively reviewed, but in the larger currents of commerce, home, and the public square.

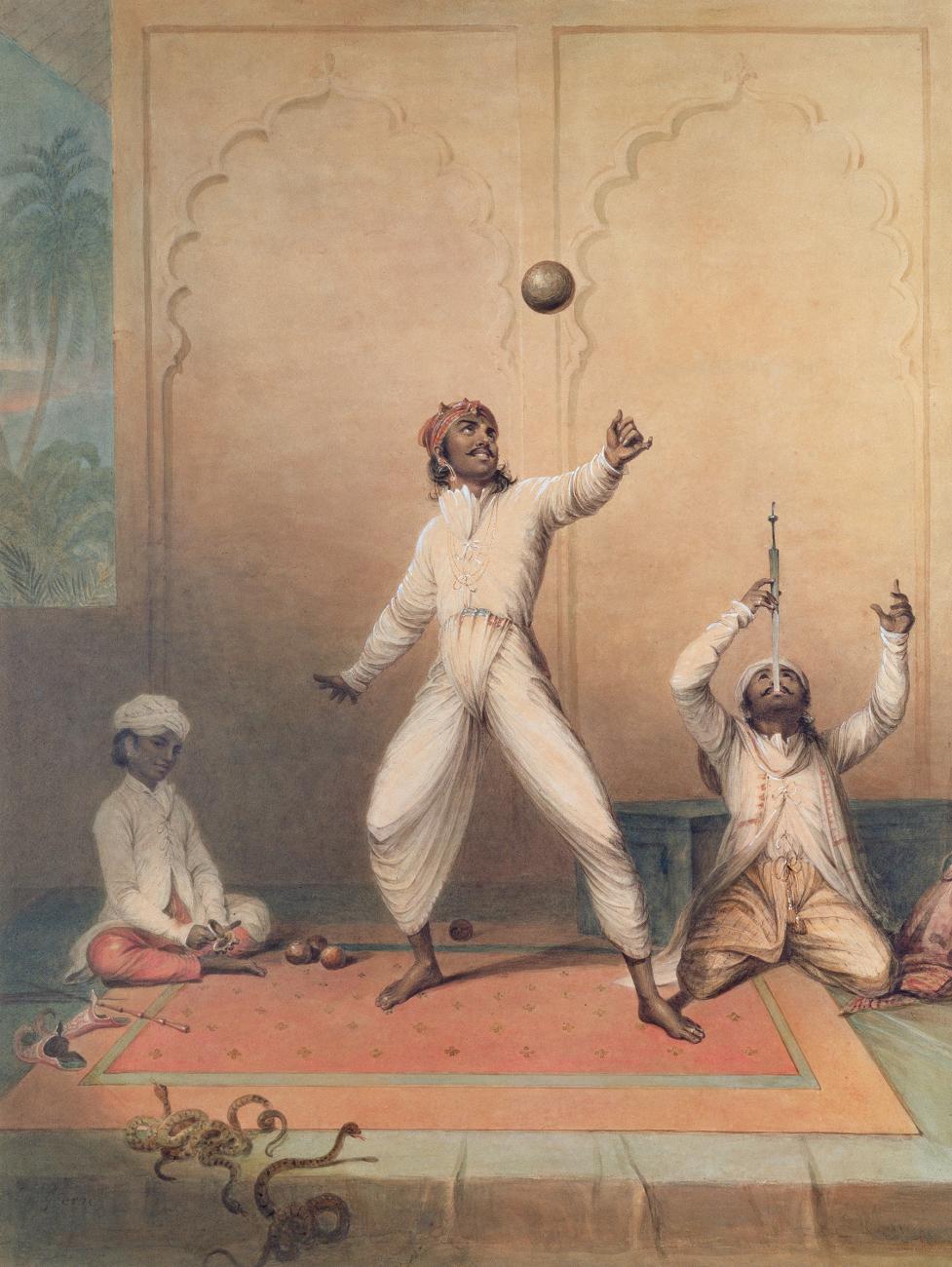

Such commentaries on the passing public scene as the New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” column, for example, extend Hazlitt’s sense of city life as a form of theater in itself. That ideal informs one of his most famous essays, “The Indian Jugglers,” which recounts a juggling performance at London’s Olympic New Theatre in 1815.

Rather than simply applying his skills as a drama critic to review a spectacle that most other writers would have dismissed as a mere entertainment, a frivolous carnival act, Hazlitt uses the feats of the jugglers to contemplate the

nature of genius:

Coming forward and seating himself on the ground in his white dress and tightened turban, the chief of the Indian Jugglers begins with tossing up two brass balls, which is what any of us could do, and concludes with keeping up four at the same time, which is what none of us could do to save our lives, nor if we were to take our whole lives to do it in. Is it then a trifling power we see at work, or is it not something next to miraculous?

Hazlitt was a great admirer of physical grace, which enabled him, as Wu argues, to create sports commentary as we now know it. One of his seminal works in that regard is “The Fight,” an 1822 magazine essay that chronicles a December 11, 1821, boxing match between Tom Hickman, nicknamed the “Gas-man,” and Bill Neate. With its puckish humor and eye for detail, the essay anticipates the boxing commentaries that A. J. Liebling would write in the 1950s. The essay’s opening passage, relating Hazlitt’s misadventure in finding lodging before the fight, nods toward an even more distant future. Unable to secure a bed, Hazlitt sits up all night in an inn, regaled by a fellow customer whose skills at verbal sparring parallel neatly with the raised fists of the boxers the essay is ostensibly about. Hazlitt gets it all on paper, and his story, which is as much about what goes on outside the ring, places the writer’s experience at the center of the narrative, much like the magazine pieces that Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, and Truman Capote would popularize as the so-called New Journalism in the 1960s.

Hazlitt, true to his visionary sensibility, was doing it generations earlier.

The big takeaway from “London Solitude”—that one can feel alone in the midst of many—offers a counterintuitive insight, another Hazlitt trademark. He was fond of turning commonly held assumptions on their heads, as in one of his most iconic essays, “On the Pleasure of Hating.” As the title suggests, Hazlitt argues that hate isn’t merely an occasional lapse in human character, but a malady that persists precisely because, for all the grave consequences, it’s utterly enjoyable:

Nature seems, (the more we look into it) made up of antipathies: without something to hate, we should lose the very spring of thought and action. Life would turn to a stagnant pool, were it not ruffled by the jarring interests, the unruly passions, of men. The white streak in our own fortunes is brightened (or just rendered visible) by making all around it as dark as possible; so the rainbow paints its form upon the cloud.

Hazlitt’s habit of challenging convention was a family tradition. He was born in 1778 in Maidstone, England, the son of a Unitarian minister whose support of the American cause in the Revolutionary War alienated him from his congregation. The family moved to America for a few years, eventually returning to England. As he matured, the young Hazlitt’s politics proved equally radical for his time and place. He disliked the idea of monarchy and idolized Napoleon as a champion of revolution, reflexively forgiving the French leader’s dictatorial excesses, which included giving himself a crown.

In his most reflective moments, Hazlitt seemed aware of his intellectual inconsistencies, as when he described his ambition to “prove an argument in the teeth of facts.” He was equally in touch with his fallibilities when he declared, “I am fond of arguing.”

Hazlitt’s contentious streak frustrated his friendships and complicated his professional life. He often rebuffed those who could help him, and his writing career was, for the most part, an unreliable mix of freelance assignments that left him in poverty.

“As a young man, Hazlitt became irretrievably disposed to quarrel with those close to him, including seniors such as Coleridge and Wordsworth, who had shown him much favor,” scholar Frederic Raphael noted.

When Hazlitt wrote in “London Solitude” about the feeling of separation from society, he was drawing on direct experience. He crafted the essay in 1830, the same year he died from stomach cancer, almost alone, in a rented room after two failed marriages and financial failure.

Nearly two centuries after his death, William Hazlitt still seems to exist in the margins. He registers with many of us, if he registers at all, as a dim figure from college English, briefly consulted, then forgotten. Few read him anymore.

A number of things have complicated Hazlitt’s literary standing. As Raphael has pointed out, “he produced no single masterpiece, nor did he impress his contemporaries with startling innovations or dazzling fame.”

Hazlitt’s one attempt at a magnum opus, his biography of Napoleon, was an embarrassing exercise in hagiography, mercifully relegated to obscurity after it was published. His true gifts were in journalism, a craft he undertook after opting not to follow his father into the ministry, then failing to establish himself as a painter.

As with Ralph Waldo Emerson, another would-be preacher-turned-essayist, Hazlitt’s literary voice occasionally betrays the excesses of the pulpit. One sometimes gets the sense that he’s speaking at the reader, not to him. He’s not a consistently endearing essayist in the vein of his on-again, off-again friend Charles Lamb, or the founding father of the genre, Michel de Montaigne.

“He was too much the moralizer and too little the moralist,” Epstein perceptively notes of Hazlitt. “Montaigne looked to himself to understand the world. Hazlitt looked at the world in puzzlement over why it did not understand him. Not quite the same thing.”

Epstein also mentions Hazlitt’s messy personal life, which included, in addition to his doomed marriages and other estrangements, an infatuation with Sarah Walker, the daughter of a tailor with whom Hazlitt was boarding. She wasn’t really interested in him and refused his proposal of marriage, a rejection that played into Liber Amoris, his tawdry and self-absorbed account of his obsession.

“But in order to admire Hazlitt you don’t even have to like him,” Epstein adds. “His talent, which was doubtless inseparable from his crotchets, his intellectual aggression, his thorny nature, simply commands attention.”

As Virginia Woolf suggested, the appeal of Hazlitt’s writing—and its abiding complication—is its passion. “His essays are emphatically himself,” she writes. “He has no reticence and he has no shame. He tells us exactly what he thinks, and he tells us—the confidence is less seductive—exactly what he feels. . . . Certainly no one could read Hazlitt and maintain a simple and uncompounded idea of him.”

Woolf also hints that the urgencies of deadlines and his financial struggles kept Hazlitt’s work from reaching its potential. James puts it more bluntly: “Hazlitt made his living as a freelance journalist, and there has always been a tendency, for a man in that occupation, for the pen to run off on its own.”

Hazlitt’s complete works fill more than 20 volumes, and anthologists have done an uneven job of culling from this massive trove the pieces that are truly memorable, a challenge that has also, one gathers, diminished his profile. In William Hazlitt: Selected Writings, editor Jon Cook dutifully collects some standout essays, although in the interest of scholarly breadth, he also throws in some selections that haven’t aged well, such as excerpts from Hazlitt’s book about Napoleon. A sharper and more accessible read is Wu’s All That Is Worth Remembering: Selected Essays.

Here is Wu’s case for his literary hero: “Why read Hazlitt today? Because no one celebrates better than he did the imaginative power of the mind as it invests itself in theatre, painting, literature, music and philosophy. But there is nothing fanciful or lightweight about him. . . . That undeluded vision makes him as compelling as ever.”

“People in the grasp of death,” Hazlitt writes, “wish all the evil they have done (as well as all the good) to be known, not to make atonement by confession, but to excite one more strong sensation before they die, and to leave their interests and passions a legacy to posterity, when they themselves are exempt from the consequences.”

That legacy lives in Hazlitt’s prose. He was a complicated man whose essays consistently remind us that humanity, with all its muddles and miracles, is a decidedly mixed bag.